|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Biopics

- Flashback Films

- Glynis Johns Films

- Historical Drama

- Inventors

- Leo Genn Films

- Margaret Rutherford Films

- Maria Schell Films

- Michael Redgrave Films

- Peter Ustinov Films

- Richard Attenborough Films

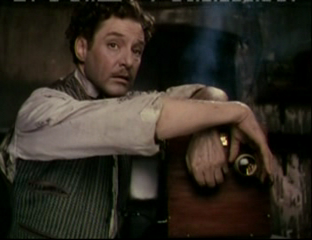

- Robert Donat Films

Review:

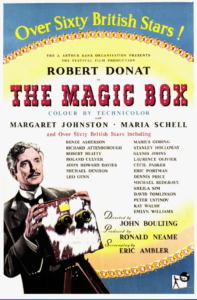

The Magic Box was the English film industry’s contribution to 1951’s Festival of Britain — a national event meant to boost public morale and, post-WWII, to “remind the world of Britain’s contribution to past, present, and future contributions to society, culture, and technological progress”. It’s fitting, then, that The Magic Box is a somewhat reverential film dedicated to chronicling the life of an unsung, largely unknown British inventor named William Friese-Greene, who ran neck-to-neck with Thomas Edison (and others) in an unofficial race to invent the first “moving picture machine”. Big-name British stars forsook their usual salaries for a chance to participate, and cameo appearances — from Richard Attenborough to Glynis Johns to Laurence Olivier — abound.

Friese-Greene (at least as portrayed here by Robert Donat) was a most frustrating individual: his single-minded devotion to cinematic invention wreaks havoc on both his marriages, forces his famil(ies) to live in dire poverty, and, tragically, prompts his three eldest sons to enlist in WWI in order to avoid being a financial burden. In a truly heartbreaking scene, Friese-Greene must comfort one of his teenage sons who has come home from school sobbing because a classmate called his father a “liar and a thief” — the former because Friese-Greene’s scientific contributions were unmentioned in the encyclopedias of the day, and the latter because of his lifetime of chronic debt and borrowing.

Indeed, examples of Friese-Greene’s economic duress — and his “creative” means of getting around it — abound. In one early scene, he actually scams a woman who has come to sit for a portrait: having pawned the last of his photographic slides to earn money for his pregnant wife’s medications, he nonetheless doesn’t want to pass up the opportunity for a sale, so he asks the gullible woman for a deposit and pretends to take her photo, planning to recoup some of his slides with her money, inform her the next day that an “accident” occurred with her original shots, and then “re-shoot” them. He’s clever, to be sure, but his ploy is also skanky, and the scene is decidedly discomfiting.

Friese-Greene’s chronic money troubles are all the more frustrating given that he eventually, through sheer luck and gumption, does make a name for himself, and is clearly capable of bringing in a decent income — only to lose it all by stubbornly refusing to maintain a sane balance between work and experimentation. We’re (perhaps) meant to sympathize with his drive for innovation, given that he openly lambastes his business partner for caring only about money (doesn’t he realize that without inventors like him, there wouldn’t be any products to peddle?!), but in the meantime, his first wife becomes literally ill with worry, and eventually dies, while his second wife finally leaves him in order to support herself and her sons. Screenwriter Eric Ambler — working from a biography by Ray Allister — should probably be commended for not shying away from the uglier truths of Friese-Greene’s life, yet the end result is that we don’t really want to feel much appreciation for this somewhat pathetic and misguided — albeit undeniably hardworking and visionary — dreamer.

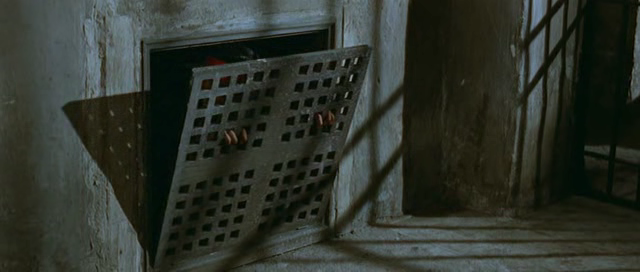

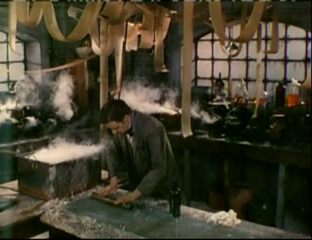

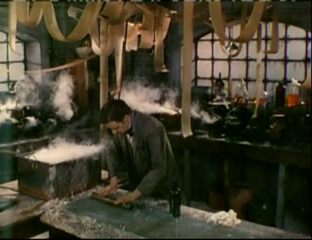

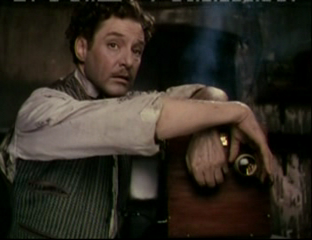

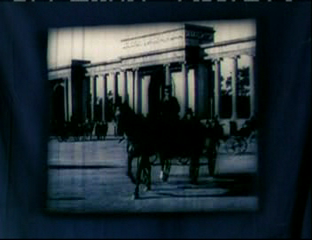

I’m of two minds about Donat’s performance: while he’s excellent at portraying Friese-Greene’s single-minded devotion to his pursuits, once he’s an older man he seems to be trying a little bit too hard — a la Mr. Chips — for sympathy. Faring better are his two wives, played with gusto by Margaret Johnston (who narrates the first flashback sequence of the film) and Maria Schell, who, for better or for worse, remains loyal to her husband until the day she dies. Most interesting of all, however, is the behind-the-scenes look we get at Friese-Greene hard at work in his laboratory: the sequence in which he finally tries out his new “moving pictures camera” — with Hyde Park coming to life inside his building — is genuinely moving, and reminds one how innovative and exciting this art form we now take for granted once was.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- An interesting look at the early days of cinematic innovation

- Maria Schell as Helena Friese-Greene

- Margaret Johnston as Edith Harrison Friese-Greene

- Donat’s discovery — witnessed by Laurence Olivier in a cameo role as a passing policeman — that he has at long last created something momentous

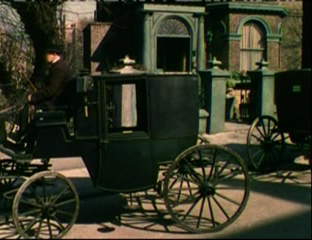

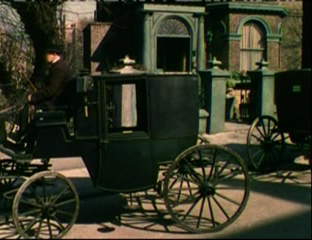

- A fine recreation of Victorian England

Must See?

No, but it’s certainly worth a look.

Links:

|