|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Cybill Shepherd Films

- Harvey Keitel Films

- Jodie Foster Films

- Martin Scorsese Films

- Misfits

- New York City

- Paul Schrader Films

- Peter Boyle Films

- Prostitutes and Gigolos

- Robert De Niro Films

- Veterans

- Vigilantes

Response to Peary’s Review:

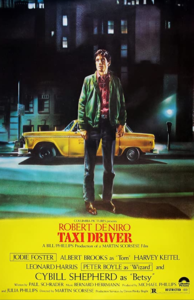

Martin Scorsese has made so many highly regarded movies over the past few decades that it’s difficult to call out which ones are most enduring, but I cast my vote for placing this “controversial, disturbing character study” — a true neo-noir classic — at the top of the list. A rare marriage of polished directorial style, stunning cinematography (by Michael Chapman), sharp script (by Paul Schrader), haunting score (by Bernard Herrmann — his last), and a chilling central performance, Taxi Driver is one of the most memorable character studies in cinematic history. Yet while Peary notes that the “film remains an enormous favorite among critics and fans who are impressed by its gritty realism, orgiastic violence, standout performances, and overwhelming cynicism”, he argues that “an equal number resent it because of its bleak resolution.” It’s difficult to tell exactly where Peary himself falls along this spectrum of opinions: while he notes that “De Niro has never been better”, he simultaneously argues that “too often Scorsese lets his favorite actor do a standard ‘De Niro bit'”, and he questions what he sees as the film’s ultimate claim that “a maniac can rid himself of inner demons… and become all civilized by committing cold-blooded murder.”

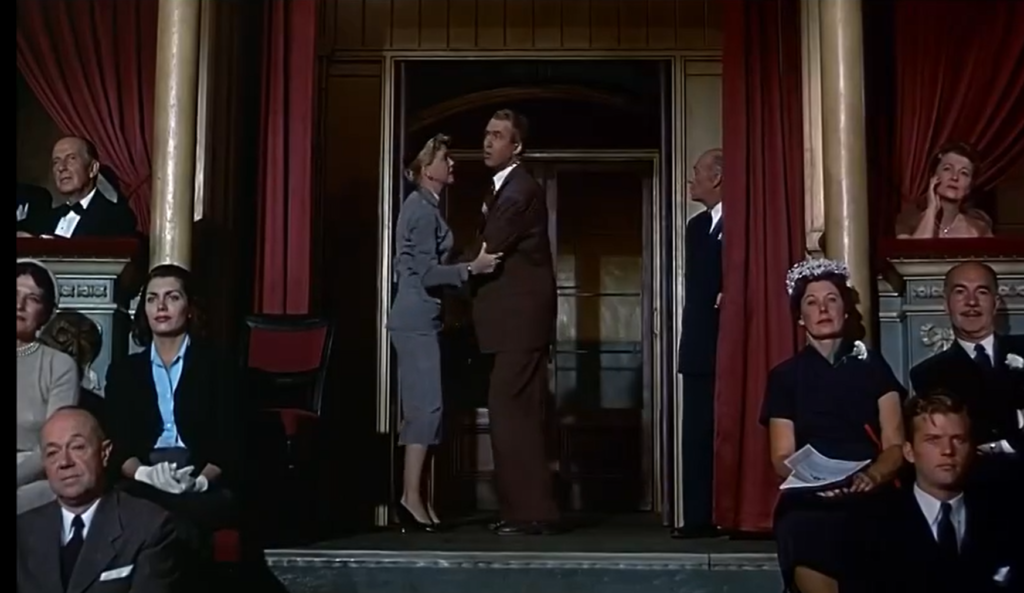

Regardless of one’s view on the film’s unexpected ending — which I see as an appropriately bizarre capstone to the dizzying parable that’s come before, akin to the controversial ending in Scorsese’s later King of Comedy (1982) — there is much to admire in Taxi Driver, including uniformly excellent performances by all involved — including Foster as a remarkably self-assured preteen hooker:

… Harvey Keitel as her creepy pimp:

… Cybill Shepherd as a WASP-y electioneer (De Niro’s love interest):

… and (despite Peary’s guarded protestations) De Niro himself in the title role. While his infamous “You talkin’ to me?” mirror scene is deservedly lauded (De Niro is indeed “terrifying” during this moment):

… his entire characterization of Travis Bickle is fascinating to watch, as Bickle gradually descends into righteous madness, driven by a complex cocktail of PTSD, sleeplessness, headaches, and a confused moral compass.

(Interestingly, we never learn why Bickle — a Vietnam vet — was discharged from the army, but he’s clearly deeply damaged, and remains alienated from those around him — as evidenced most clearly in his futile attempt to turn to a colleague, Peter Boyle, for help).

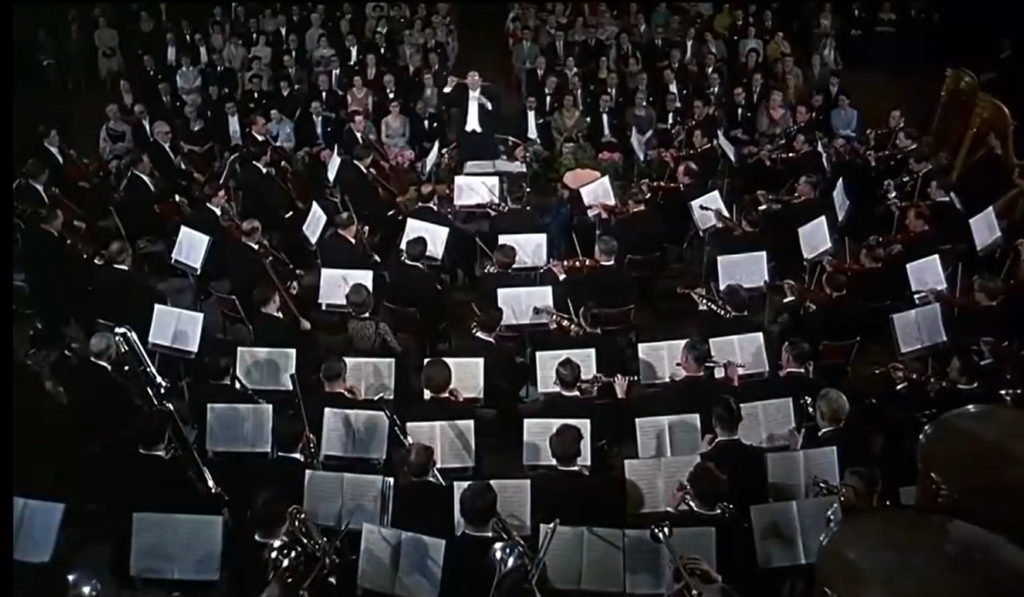

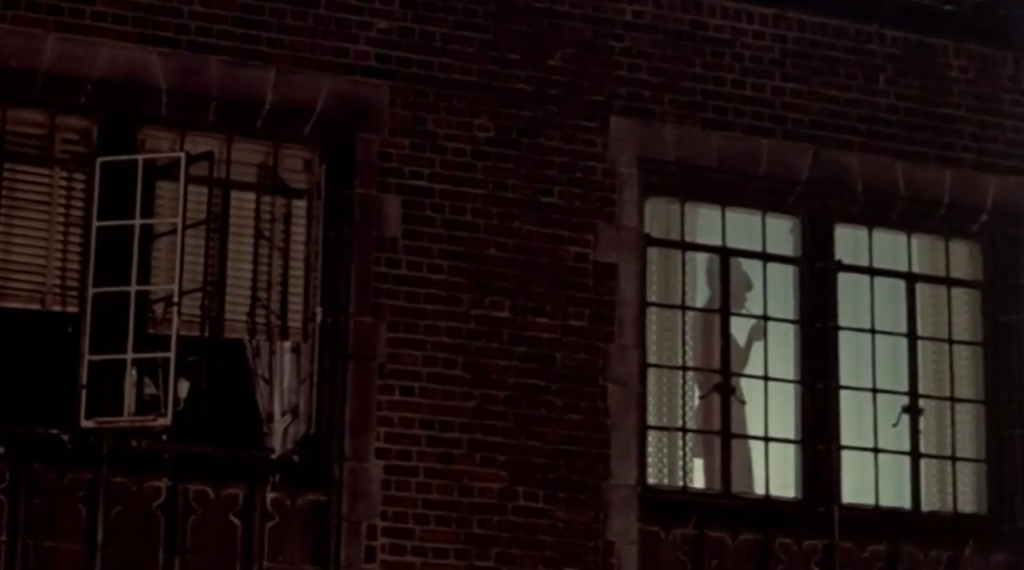

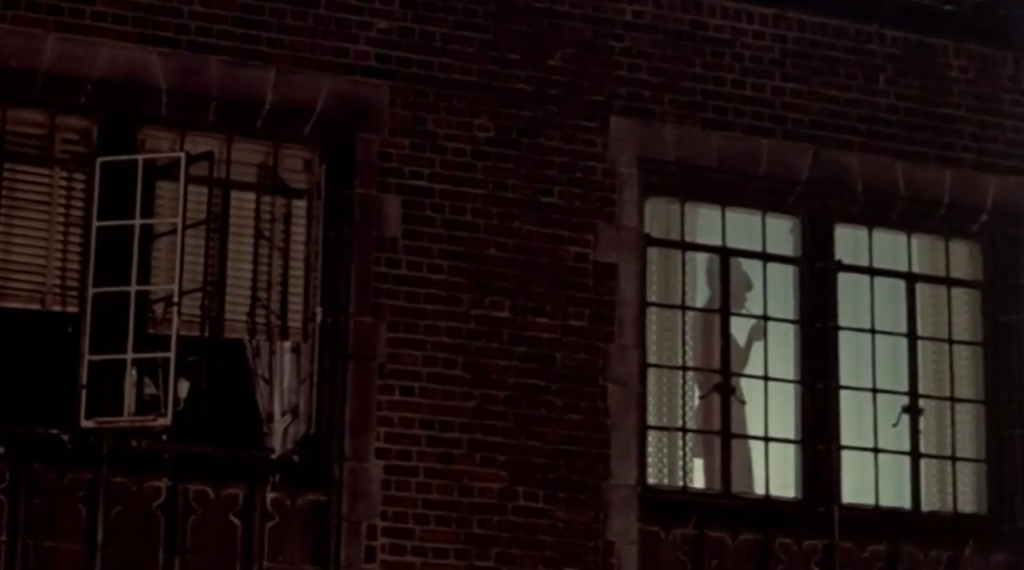

While Taxi Driver is undeniably a violence-filled movie, Peary accurately notes that many of the film’s “best moments” are those without violence — such as the “surreal rides De Niro takes in his cab”, which (thanks in large part to cinematographer Michael Chapman) are “beautifully shot mood pieces”; as Peary points out, “no director has better captured the peculiarly wretched feel and odor, as well as the look, of the underbelly of New York.”

Another of my favorite scenes (among many) shows Jodie Foster picking at a grilled cheese sandwich while defending her lifestyle in front of De Niro’s incredulous Bickle; it’s clear that Bickle’s noble obsession to “rescue” her from her pimp — much like John Wayne’s quest to rescue Natalie Wood from her Indian captors in The Searchers (Peary calls out this parallel in his review) — will be met with a decided lack of gratitude, further complicating this enigmatic tale of a self-made redeemer in search of “justice”.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Robert De Niro as Travis Bickle (voted Best Actor of the Year in Peary’s Alternate Oscars book, where he changes his tune slightly and insists his “gripes about Travis’s character have only to do with the script, not De Niro’s performance”)

- Jodie Foster as Iris

- Michael Chapman’s cinematography

- Scorsese’s direction

- Paul Schrader’s uncompromising script

- Bernard Herrmann’s score

Must See?

Of course — numerous times. Discussed at length in Peary’s Cult Movies 2.

Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|