Reflections on Must-See Films From 1964

It’s time for another reflection on a particular year in cinema! So far I’ve shared my thoughts on must-see titles from 1960, 1961, 1962, and 1963 — and now I’m (nearly) done reviewing all titles from 1964. While there were certainly some cheery escapist flicks released that year — Mary Poppins, anyone? — darkness pervaded in powerful cinematic depictions of politics, war, plague, racism, romantic loss, and more.

- Out of 82 total titles from 1964, I voted 36 – or 44% – as must see. Not many are foreign (non-American) titles; I count only ten, with one French (The Umbrellas of Cherbourg), one Armenian (Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors), five British, one Italian, and two Japanese.

- Of the latter, Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Woman in the Dunes — about a man and woman who “form an unexpectedly sweet bond of captivity, supporting one another through work, companionship, and sensual connection” — remains “a one-of-a-kind masterpiece from mid-20th century Japanese cinema,” and is well worth a look if you haven’t yet seen it.

- Of the five British titles, two are of special note — starting with Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo’s It Happened Here, a frighteningly realistic “alternative history” of a Nazi-controlled post-WWII England. Made over eight years and with the collaborative support of countless volunteers, the directors show us an every-woman nurse who agrees to be employed by her nation’s quasi-paramilitary organization — “figuring it’s better to work towards social stability of some kind (any kind) than to be part of continued violent resistance” — and whose passive acceptance of an openly Fascist government gives us a “frightening reminder of how easy it is for humans to simply accept the reality around them as normal.”

- On a much lighter note, Richard Lester’s A Hard Day’s Night remains a cult favorite which hasn’t dated in the slightest. While “the young Beatles’ infectious enthusiasm for life and music… is the biggest draw by far,” “I also love the sly supporting performances…; the ‘mod’ sets; the consistently creative camera moves and angles; and the wonderful subplot provided to ‘poor Ringo’.”

- Speaking of cult titles, I revisited and wrote my review of Roger Corman’s The Masque of the Red Death in March of 2020, pointing out at the time that this “film about an evil nobleman and his willing compatriots denying refuge to plaintive villagers provides a potent cautionary tale about the need to continuously support one another through the hardest of times, across all boundaries: social, economic, racial, and religious.”

- Political thrillers were dominant in 1964 cinema. John Frankenheimer’s Seven Days in May — with a script by Ray Sterling — remains freakily relevant to current politics, reminding us that “when a group of individuals is convinced they’re right and the well-being of their nation is at risk, we know they will stop at nothing.”

- Meanwhile, Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb deserves its continued status as a classic favorite, with tour-de-force performances by Peter Sellers (as Group Captain Lionel Mandrake, President Merkin Muffley, and Dr. Strangelove) and memorable turns by both Sterling Hayden and George C. Scott in key supporting roles.

- As a more serious counterpart to Dr. Strangelove, Sidney Lumet’s nuclear thriller Fail Safe — featuring stand-out performances by Henry Fonda and Larry Hagman — creates and maintains “tension across the various inter-connected spheres of the storyline (primarily the president’s office, the War Room, and the pilots’ cockpit),” and “is a literal nailbiter in terms of what will come next, with nothing less than the fate of our planet in the balance.”

- Emile De Antonio’s political documentary Point of Order rounds things out politically by “taking more than 180 hours of television footage from the 1954 Army-McCarthy hearings” and providing a “fascinating glimpse at the crash and burn of America’s most infamous ‘Commie witch hunter,'” Senator Joe McCarthy.

- In addition to Seven Days in May, John Frankenheimer and Burt Lancaster teamed up that year for The Train. True to its title, it’s “set almost entirely in, on, or around trains” and tells a gripping cat-and-mouse tale involving priceless art being shipped away for safety during World War II. As I note in my review, “With no models used (all action was real), the film possesses a consistently heady air of real-life danger, with one expertly filmed action sequence after the other.”

- Nothing But a Man was the best of the race-related films to emerge in 1964. As I note in my review, “By telling the story of ‘everyman’ Duff Anderson (Ivan Dixon), we see what occurs when a person is unable to secure reasonably paid work that allows them to maintain dignity and self-respect.” While it’s “undeniably rough to watch,” this docudrama “remains a powerful neo-realist depiction of Black Southern communities in the 1960s.”

- Sergio Leone’s seminal “spaghetti western” A Fistful of Dollars brought us Clint Eastwood with a cheroot and poncho, a “highly distinctive score” by Ennio Morricone, and an odd sense of déjà vu for anyone who’s seen Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (which it copied from heavily while building up a strong mythos of its own).

- I have a couple of personal cult favorites from this year. One is George Roy Hill’s The World of Henry Orient, a delightful dark comedy featuring “a marvelously droll turn by Peter Sellers” (it was a good year for him!) and “sparkling performances by its two unknown leads (Merrie Spaeth and Tippy Walker),” who perfectly capture “the hyper compulsion of teenage female friendship.”

The other is Viva Las Vegas (Elvis Presley finally met his on-screen match in Ann-Margret!), which is “directed with flair by George Sidney and featur[es] vivid sets and costumes, rousing song-and-dance numbers, nice use of Vegas locales, and a super-fun romantic rivalry (with plenty of genuine sparks flying).”

- Speaking of personal favorites, I was very pleasantly surprised to revisit Cary Grant and Leslie Caron in Father Goose, an enjoyable romantic comedy which “goes in surprisingly delightful and quirky directions.” Watch for “numerous memorable moments, both humorous and frightening,” with interplay between the two providing “much authentic tension.”

- John Huston’s The Night of the Iguana — based on a Tennessee Williams play — features a storyline that “merits nearly endless discussion and debate,” “crisp and gorgeous” cinematography by Gabriel Figueroa, inspired location sets (in Mexico), and “top-notch” performances across the board” — including from Richard Burton, Ava Gardner, Deborah Kerr, Grayson Hall, and Sue Lyons.

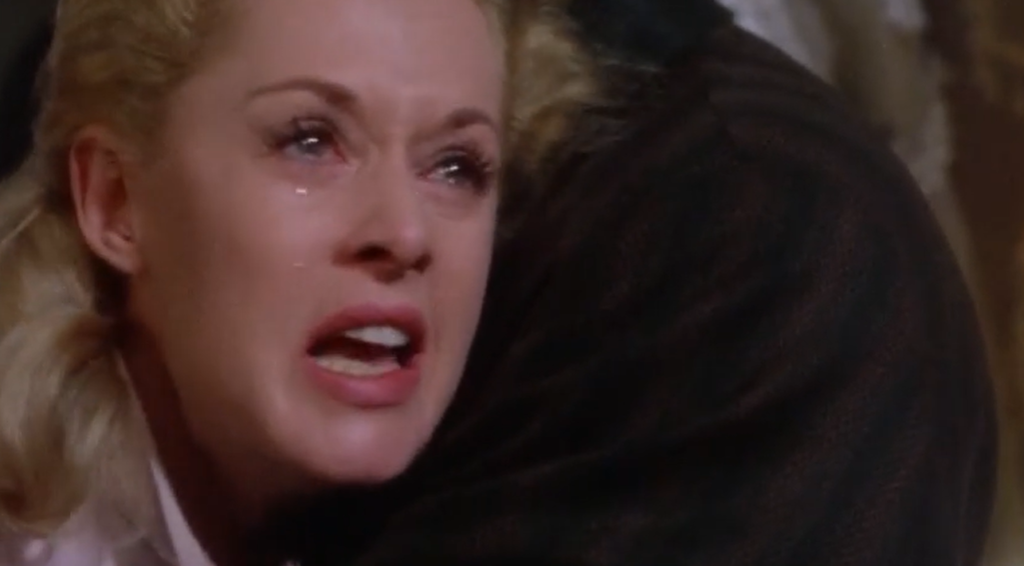

- Speaking of such luminaries, there were numerous standout female performances in 1964 — including from Ann-Margret as Jodi in a Kitten With a Whip; Joan Crawford in William Castle’s Strait-Jacket; and Tippi Hedren in Hitchcock’s Marnie.

As always, happy viewing!

One thought on “Reflections on Must-See Films From 1964”

Thanks for highlighting ‘The Night of the Iguana’ – my all-time favorite film… as well as ‘Kitten With a Whip – my all-time favorite guilty pleasure. 😉

I would be remiss if I did not allow an honorable mention for ‘The World of Henry Orient’, an exquisite, permanent double-bill for the equally exquisite ‘The Trouble with Angels’. 😉