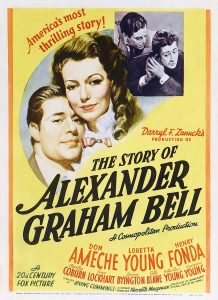

Story of Alexander Graham Bell, The (1939)

“Ladies and gentlemen, it gives me great pleasure to address you this evening — though I am in Boston, and you are in Salem.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres:

Review: … whose romance with a beautiful lass (Young): … is picture perfect (other than the pesky need for him to actually make some money in order to marry her); touching scenes of children and adults impacted by Bell’s work, including a cherub-cheeked deaf boy (Bobby Watson) who learns to communicate with his father (Gene Lockhart) for the first time, thanks to Bell’s pioneering work with Visible Speech: … droll humor in the form of Bell’s sidekick (Fonda), who repeatedly points out the need to eat every once in a while: … and a final court case: … in which Bell successfully defends the veracity of his patent against a would-be usurper (Western Union) by agreeing to share a deeply personal letter written to his beloved. Unfortunately, the too-neat storyline fails to elicit as much interest in this astonishingly prolific scientist as the subject matter should warrant, and Young is simply sappy as his all-adoring partner. This flick will primarily be of interest to those who enjoy early Hollywood biopics. Note: Hardworking Bell was brilliant beyond what he’s best known for. According to Wikipedia:

Redeeming Qualities and Moments: Must See? Links: |

One thought on “Story of Alexander Graham Bell, The (1939)”

A tentative once-must…and that’s mainly for the last 3rd of the film. I’ll explain:

Someone really should put out a book called ‘All The Untruths That Bio-Pics Ever Told’. Then we’d have a better way of approaching films like this. It’s often much harder to assess a film while not knowing the reality of what we’re watching.

We can sense (as is the case here) when much of a film feels like a typical Hollywood product: when parts of it feel sappy or forced; when parts feel intended as ‘heroic’ in some way because that’s more ‘American’. When we happen to know (now) for a fact that certain information is an outright lie (i.e. Cary Grant depicting Cole Porter as heterosexual in ‘Night and Day’), we are likely to want to wash our hands of the entire film. As well, studios (especially in this era) not only wanted to make money by selling an ‘acceptable’ product that the public would eagerly promote, but they also often wanted to avoid lawsuits for various reasons.

(Of course, admittedly, when ‘Night and Day’ was made, it was unthinkable to even breathe the word ‘homosexual’. I guess that’s another matter.)

This is one reason why a film like Mark Rydell’s ‘The Rose’ was such a good idea. Everybody knew it was ‘based on’ the life of Janis Joplin – but it never said it was (and her name wasn’t used). As a result, when we watch it, we don’t have to concern ourselves about whether we’re being duped or not.

Most of the earlier parts of this film about A.G. Bell feel typically Hollywood (often not in a good way). That can make it kind of a chore to get through. But then the film gets to the section re: the court case involving the patent for Bell’s invention. If the details of the trial (as depicted in the film) are not as they happened, they at least feel believable as such. The whole end of the film is devoted to that court case – and it’s compelling. It also sheds a harsh but necessary light on the element of greed in human nature (which gives this film added worth).