“The girl’s name is Rosemonde.”

|

Synopsis:

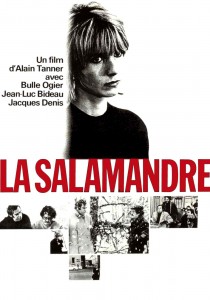

Two writer friends (Jean-Luc Bideau and Jacques Denis) research a contested news story concerning an enigmatic young woman (Bulle Ogier) who may have deliberately shot her uncle.

|

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Character Studies

- Love Triangle

- Swiss Films

- Working Class

- Writers

Review:

Alain Tanner’s second feature film — a clever satire on the writing process and ‘truth’ in reporting — provocatively explores the nature of veracity in storytelling, and the ways in which personal involvement inevitably skews our perception. While not as pointed as his debut film — Charles, Dead or Alive (1969) — or as openly humorous as his later, more accessible ensemble film Jonah, Who Will Be 25 in the Year 2000 (1976), La Salamandre remains a classic entry in Tanner’s oeuvre.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Bulle Ogier as the seductive, sullen Rosemonde

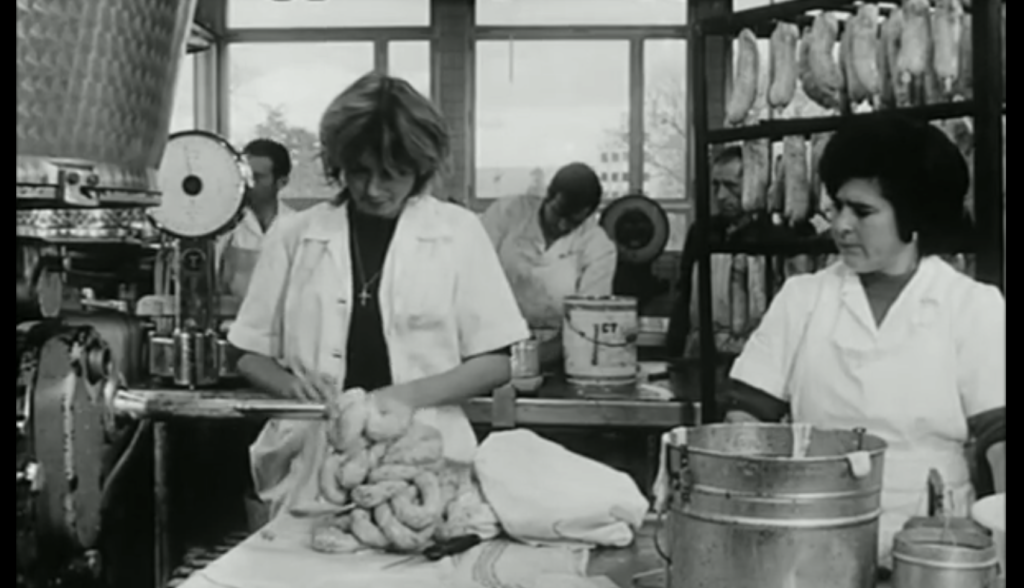

- An unromanticized look at the boredom and limited prospects of working-class life

Must See?

No, but it’s recommended.

Links:

|

One thought on “Salamandre, La (1971)”

First viewing. Not must-see.

Apparently I’m not much of a Tanner fan. I looked back at what I said about his other films (the ones I’ve seen) – and I guess I don’t have much of a feel for what he does.

In the case of this particular film… I rather liked the premise as it unveiled itself (two male characters working on a ‘true story’ writing project that will result in a collaborative truth combined from different angles) – and, for awhile, as the film progressed along those lines, I started to feel confident that *that* was where the storyline would stay.

But the film, in its latter half, goes to a different and more challenging place (which is fine… except that I was somewhat bored by the way the challenge plays out). In constructing their portrait of Ogier, the two men realize that – whether capturing their ‘subject’ via facts or fantasy – their project will fail because Ogier (as Denis observes) is not unlike a salamander (whose nature is to be deceptive in how it appears).

The two men do eventually get where they ultimately want to be with their subject but – it seems to me – at the cost of the film’s viewers, as well as Tanner’s film itself. The film seems to want to make a statement about the impossibility of capturing the truth about another human being – but I daresay the process becomes much easier and rather more reliable if the person you’re documenting isn’t crazy to begin with.

I wouldn’t go so far as to call this film pretentious. There’s a marked intelligence here and the film may work for some on the level of a ‘brain-tease’. But its uneven tone and indifferent approach to clarity can make for a frustrating watch.