To Kill a Mockingbird (1962)

“There’s a lot of ugly things in this world, son. I wish I could keep ’em all away from you. That’s never possible.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

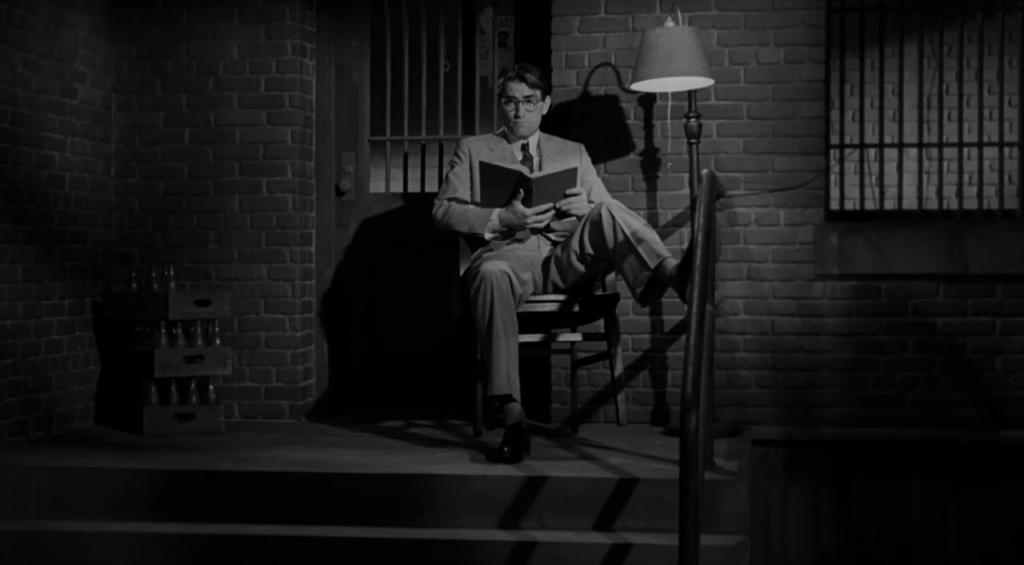

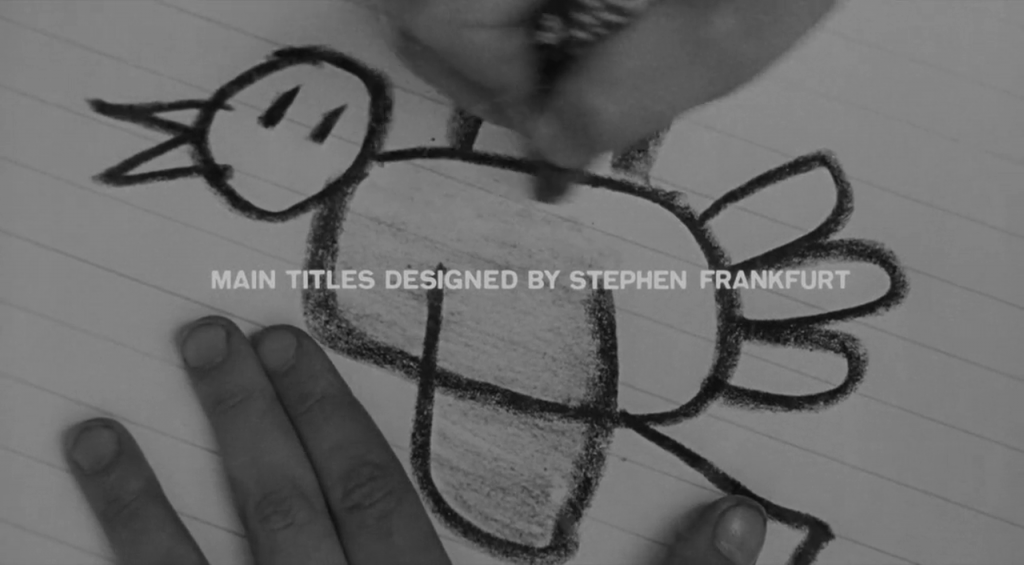

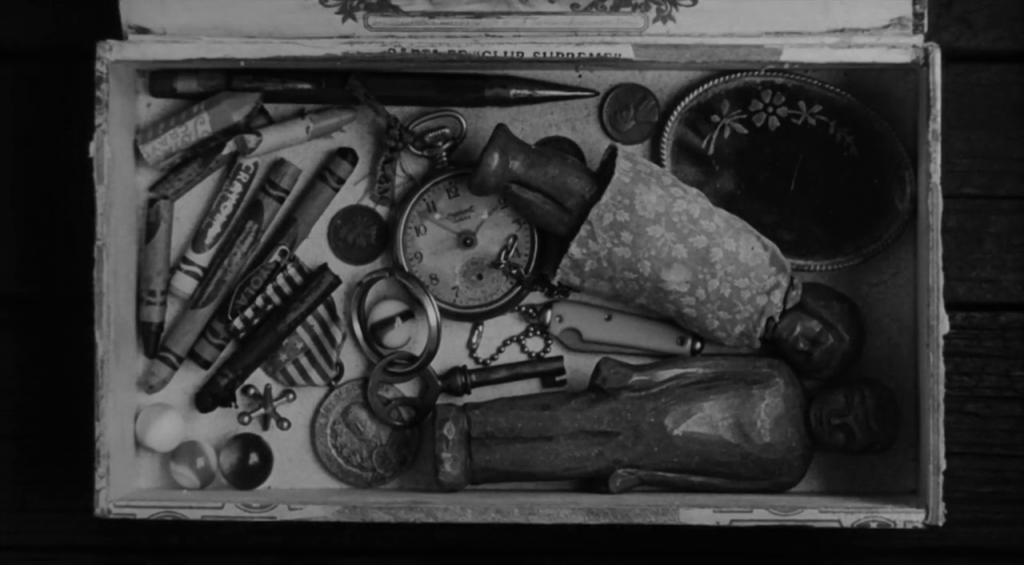

Review: I’m not sure this matters or is even accurate: Atticus openly acknowledges that his strategy will involve appealing the foregone conclusion (guilty) of a racist jury; his “deliberate, low-keyed courtroom summation” — which Peary wishes “had more fire” — makes complete sense in the context of his deeply racist town, where simply the act of defending an (innocent) black man can bring death threats to his family. Regardless of how one feels about Peck’s performance, To Kill a Mockingbird remains a classic on many levels — beginning with Elmer Bernstein’s instantly recognizable score, which is impossible to extricate from one’s experience of the film. Equally poignant is Atticus’s relationship with his kids: Peck most definitely was “the man you’d want for your father”, and it’s hard to believe any child watching this movie wouldn’t melt with envy at the sight of Atticus cuddling Scout (Badham) in his lap: … or allowing Jem (Alford) the opportunity to accompany him on a life-changing visit to Peters’ house. Speaking of Scout and Jem, the screenplay’s child-driven perspective (Kim Stanley narrates in flashback, as Scout-grown-up) is yet another successful facet: the entire story is framed within the nostalgia-tinged reminiscences of a young girl smitten by her father’s love, courage, and wisdom. TKAM could be viewed as a meditation on the universal desire — however fleeting — to admire one’s parent(s) as the epitome of all that is right about the world. Badham and Alford’s performances (neither pursued a long-term acting career) are among the best given by child actors; while Megna is fine as young Truman Capote (er, “Dill”), he’s clearly more suited to a supporting role. Peters, previously cast as villains, is heartbreaking as the wrongly accused man who had the temerity to “feel sorry for a white woman”; his impossible situation highlights racism’s toxic blight on humanity, a reality which Horton Foote doesn’t shy away from in his adapted screenplay. With that said, it’s a little disconcerting SPOILER ALERT how abruptly the narrative shifts in the final half-hour from Peters’ brutal murder to the subplot about a mysterious, “ultra-white” neighbor (Duvall) who saves Atticus’s kids. Ultimately, however, the ending vividly illustrates the need for decent individuals to protect one another no matter the cost, and for diversity to be not only accepted but embraced. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |

One thought on “To Kill a Mockingbird (1962)”

A no-brainer must.

This is another one of those films that I happened to see as a youngster countless times, since it was a tv staple – it seemed that every time you turned around, it was being shown again.

Since it’s a story told from a child’s POV, it makes that much more sense that parents should make sure that their kids see it – whether they have a strong interest in film or not. What the film has to say about racism – and prejudice in general – is invaluable and should be absorbed at a young age.

Even though ‘TKAM’ is set in a specific time period, it still seems ageless, and it has held up well. I saw it again not that long ago when it was released as a blu-ray. It still packs quite a punch while, simultaneously, it is to be applauded for being among the most sensitive of portraits of children and the world they live in.