|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

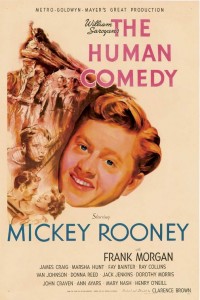

- Clarence Brown Films

- Coming of Age

- Donna Reed Films

- Fay Bainter Films

- Frank Morgan Films

- Mickey Rooney Films

- Small Town America

- Van Johnson Films

- World War Two

Response to Peary’s Review:

Peary acknowledges that “director Clarence Brown shamelessly pulls all our heartstrings” in “this beautifully realized adaptation of Williams Saroyan’s wonderful novel about life in a small town during WWII”. He lists all the elements of “Americana” we see as the gently episodic film progresses, arguing that “we can’t help but feel waves of nostalgia, religion, and patriotism and develop a sense of family, duty/responsibility, and brotherhood” as a result. He calls out Mickey Rooney’s “moving performance as Homer McCauley”, and notes that the film is “filled with characters you’ll recognize, events that you may also have lived”. He asserts that “every few minutes your eyes will fill with tears — over something happy, sad, noble, familiar”, and ultimately posits that the “picture’s major theme is simple: all Americans are equal, all orphans in America… are part of the American family”.

I’m not quite as enamored with the film as Peary (who nominates it as one of the Best Pictures of the Year in his Alternate Oscars). My sentiments are much more aligned with those of DVD Savant, who writes that “the movie has all the faults of a wartime film tailored for morale purposes, and as such offers a strange mix of Saroyan’s poetry (too much of it, in fact) and overbearing MGM sentiment”, yet concedes that “despite its flaws the film is as touching now as it was then”. Like Savant, I feel the film “tries too hard” yet “is by no means an embarrassing hoot”, given that “most of its scenes are honest and quite a few have a wonderful, natural appeal”. Indeed, for every shamelessly hokey device (i.e., the presence of Rooney’s deceased father [Ray Collins] providing a voice-from-beyond-the-grave narration), there’s a scene that hits home in its quiet authenticity — i.e., Frank Morgan’s struggles to stay awake and sober while receiving news about heartbreaking tragedies on the front.

The performances throughout are a mixed big, with some characters coming across as simply archetypes (i.e., Bainter as a harp-playing widow; Reed as Rooney’s quietly beautiful sister) — but often this seems due simply to the material they were given to work with (or not). Rooney was rightfully Oscar-nominated for his surprisingly heartfelt and selfless portrayal as Homer Macauley; Savant accurately points out that Rooney “flawlessly” performs a critical early scene — in which he delivers a telegram to a Mexican-American woman whose son has died in the war — by simply “shut[ting] up and giv[ing] the scene over to the other actor”. Jackie ‘Butch’ Jenkins, as Homer’s little brother Ulysses, also gives an admirably “natural” performance, coming across like a real kid, not an aspiring child actor; and Morgan is pitch-perfect in his small but memorable role.

However, I’m not at all a fan of the romantic subplot between Craig and Hunt, which seems patently crafted to bolster Saroyan’s thesis that (as Peary puts it) “all Americans are equal”. Yeah, right. While it’s somewhat refreshing, I suppose, to learn that Hunt and her parents aren’t the haughty snobs one might believe them to be, we’re still never given a good reason to understand why Craig and Hunt are so in love. What attracted them to each other in the first place? To that end, Craig’s character is a frustrating cypher; he’s clearly a well-meaning, generous guy (as evidenced in a revealing early scene with a customer in his store), but nothing more is made of this tendency. Meanwhile, their “honeymoon” drive alongside a WEIRD multi-cultural festival — reminiscent of the “It’s a Small World” ride at Disneyland — is simply, as Savant puts it, “hilariously insulting”.

Note: I recall being enamored with Saroyan’s novel as a teen, and was fascinated to read (in TCM’s article) that, based on the success of his play The Time of Your Life, he was solicited to write the story as a screenplay based on his own life growing up in a small California town. (The screenplay was eventually rewritten by someone else, but Saroyan turned the material into his novel.)

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Mickey Rooney as Homer

- Frank Morgan as Mr. Grogan

- Jackie ‘Butch’ Jenkins as Ulysses

- Fine cinematography

Must See?

Yes, as a heartwarming, if somewhat dated, WWII-era classic.

Categories

Links:

|