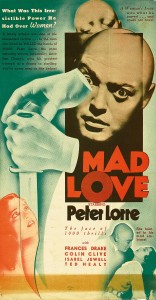

Mad Love (1935)

“I, a poor peasant, have conquered science; why can’t I conquer love?”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

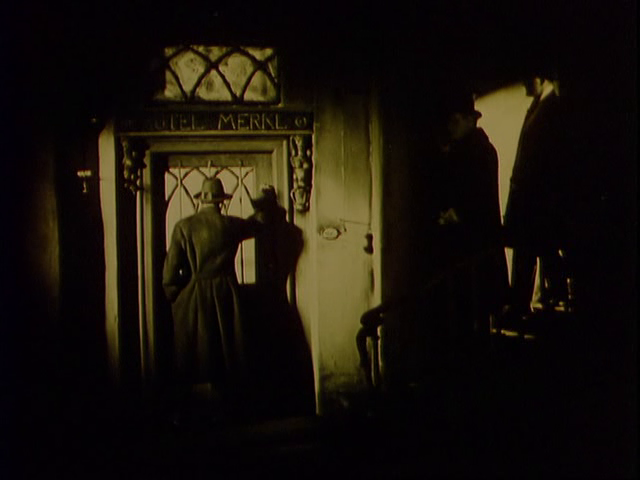

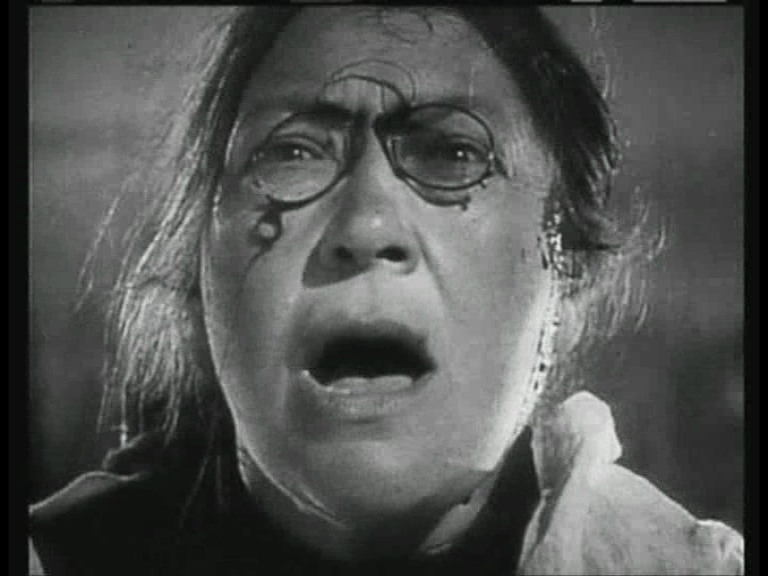

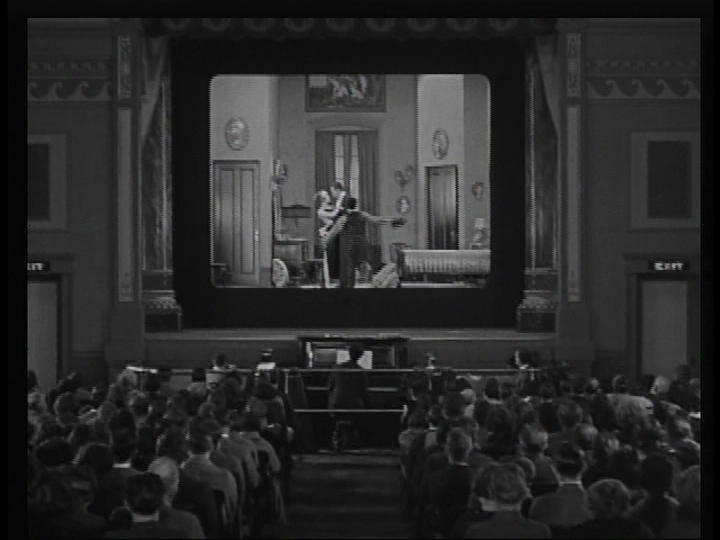

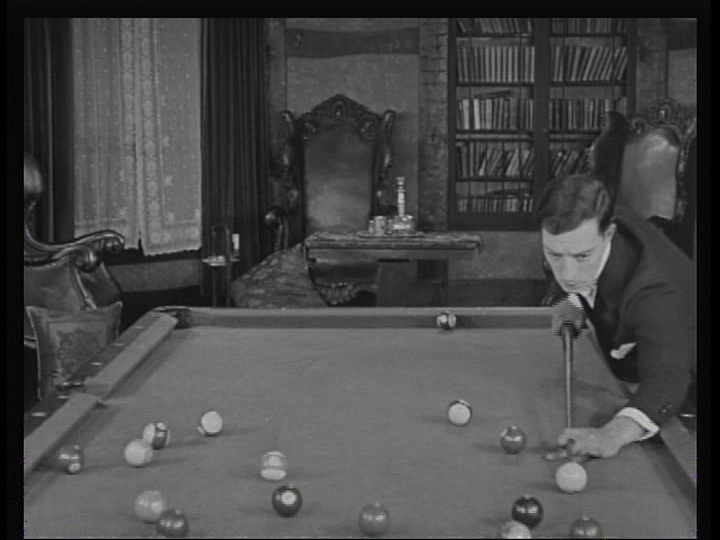

Response to Peary’s Review: … and that “thoughtful” casting leads to even the smallest parts being “well written and played”. However, he ultimately argues that the “picture’s success” is primarily attributable to its “eerie visuals”, with the finale particularly “surreal”; and he notes that the entire affair possesses an overall “hard-edged poetic quality”, with a “haunting atmosphere… created by… imaginative use of the camera”. Indeed, one would expect nothing less from a film helmed by noted DP Karl Freund (whose American directorial debut was 1932’s The Mummy), and photographed in part by another noted DP, Gregg Toland. Peary’s review succinctly sums up the fine qualities of this most enjoyable “Grand Guignol” horror flick, one which afforded Peter Lorre his breakthrough role in American movies, and which remains a gruesomely absorbing tale of obsessive love. Peary is right to call out the performance by wide-eyed Drake (who co-starred the following year in The Invisible Ray); she’s a memorable heroine-in-distress, with more to do and say than Clive (whose character feels oddly underdeveloped, though Clive does a fine job showing his increasingly distraught state of mind). Meanwhile, the intermittent presence of a wisecracking reporter (Ted Healy) feels decidedly out of place, though I’m fond of the humorous character played by May Beatty as Gogol’s tippling housekeeper. But this is really Lorre’s show all the way: He takes the material and runs with it, managing to present his villain as vaguely sympathetic, despite his nefarious plans to win Drake at any cost (he does save children’s lives through surgery, after all!). Watch for his “disguise” in the second half of the film (see second still below) — kudos to whoever was responsible for its design! Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

Links: |