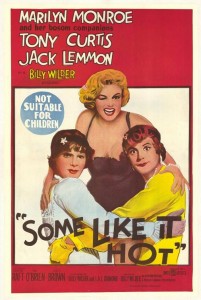

Some Like It Hot (1959)

“Now you know how the other half lives.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Response to Peary’s Review: Peary argues that SLIH features “Marilyn Monroe’s most delectable performance”, and names her Best Actress of the Year in Alternate Oscars, where he notes that while she “plays a character who has been pushed around in life… [she] doesn’t try to win audience sympathy or pass herself off as lovable, as she does in other films”. Instead, he posits, she “concentrated on comedy”, and comes across as “truly funny in this film”. Indeed, there’s truly no evidence of the infamous inter-personal conflicts between Monroe and others that plagued the film’s production. Meanwhile, Peary names Jack Lemmon Best Actor of the Year in Alternate Oscars, where he notes that Lemmon is “howlingly funny” playing a “character who is excitable, frantic, flustered, argumentative, cynical, sarcastic, curious, horny, and slightly mischievous”. What’s most impressive about Lemmon’s characterization is the way he “jumps into the zaniness [of his “insane predicament”] and allows himself to become screwy and happy”. Peary notes that “as in all of his most successful comedies, he’s appealing here because, in addition to his immense talent, he seems to be enjoying himself so much”. In his analysis of the film for GFTFF (elaborated upon in his more extensive reviews for Cult Movies 2 and Alternate Oscars), Peary notes that “in Wilder’s screen world, people are identified by what they wear, carry, or own, but by [the] film’s end, [the] characters will be identified by who they are”. He notes that “interestingly, Jerry and Joe don’t become silly movie females when they don women’s clothing”, instead becoming “tough, smart, fun-to-be-with broads who take guff from no man and are loyal friends to other women”. He points out that “like Sylvia Scarlett, [the movie’s] theme is that when a person lives as the other sex, he or she has the opportunity to explore previously latent aspects of the personality”; to that end, he argues that “Daphne and Josephine aren’t the alter egos of Jerry and Joe” so much as they are “more (extensions) of the two men”. Ultimately, SLIH remains the best and smartest of countless cross-dressing comedies to come out of Hollywood, offering an enduring treat to both first-time viewers as well as those returning for repeat visits. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |