|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Charlie Chaplin Films

- Comedy

- Depression Era

- Homeless

- Mental Breakdown

- Paulette Goddard Films

- Romance

- Silent Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

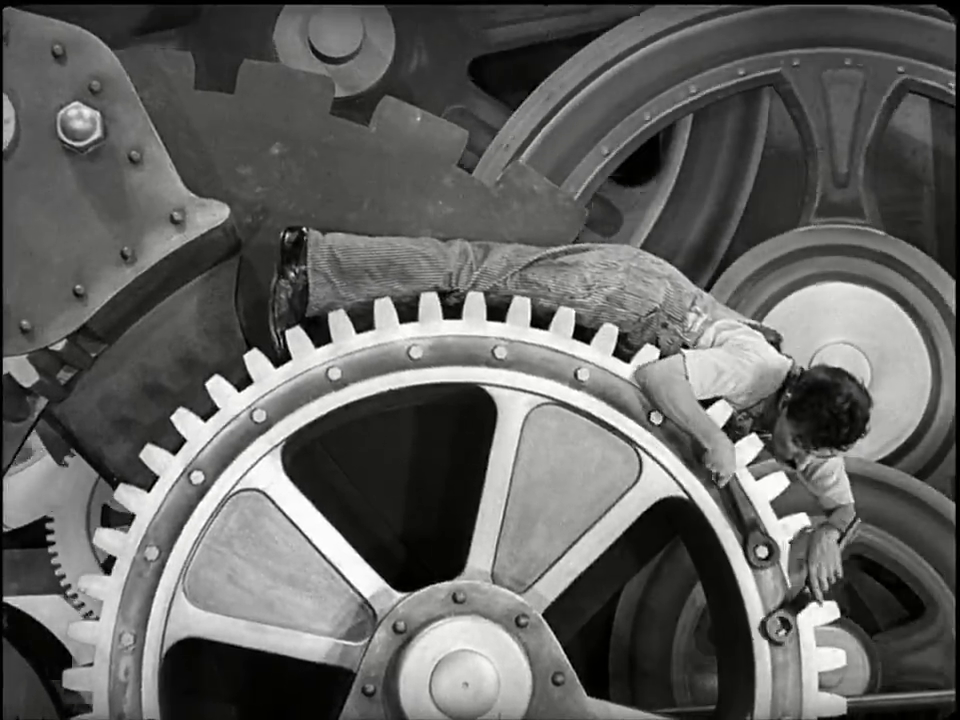

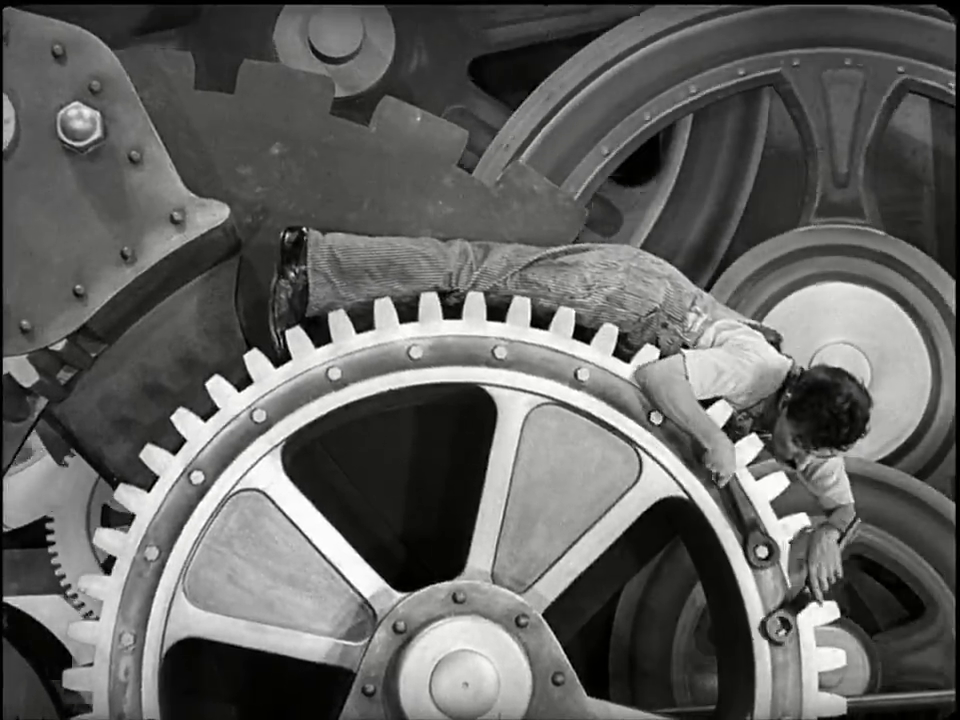

In his short GFTFF review of this “classic Charlie Chaplin film” — which “pits modern man against [the] modern, industrialized, impersonal city” — Peary writes that “in the opening sequence, it looks like man will lose out”, given that “Chaplin has a nervous breakdown while turning bolts — he becomes like a machine out of whack.” However, “Charlie will regain his humanity and maintain it, despite being tossed into jail every time he expresses human qualities at work (in his many new jobs) or on the cop-infested streets” — and it “is his new love for gamine Paulette Goddard that keeps him from ever becoming depressed or defeated.” Peary adds that “this is a surprisingly optimistic film”, despite “few good things happen[ing] to Chaplin or Goddard”, and he notes that the “chemistry between the married leads is strong — Charlie looks spiffier than we’d seen him”, and “Goddard is incredibly sexy and pretty.” He notes that highlights include “Chaplin on roller skates by a ledge, Chaplin as a singing waiter, Chaplin and Goddard walking arm and arm into the sunset.”

Peary goes into greater detail about the movie in his Alternate Oscars, where he awards it Best Picture of the Year and also gives Chaplin his second Best Actor Oscar — after The Circus (1928) — for his leading role. Peary writes that this “masterwork” was “Chaplin’s last film without actual dialogue, though it does have sound effects (from machines churning to stomachs grumbling) and music, including Chaplin’s glorious ‘Smile’ on the soundtrack and Chaplin (in the singing waiter scene) performing the studio-recorded ‘Titina’, the first time he was ever heard on film.” However, “stylistically, Chaplin remained in the silent era, with several scenes recalling specific scenes in his silent classics”. Peary writes that “Modern Times is consistently funny, but while we laugh at Chaplin’s cleverly conceived and brilliantly performed antics, we never forget that the two characters we love are in trouble and are hungry”, and points out that “the majority of scenes in the picture have something to do with food”.

In his discussion of Chaplin’s performance in Alternate Oscars, Peary notes that it is, “quite simply, wonderful” and adds that “so many images of Chaplin in Modern Times are etched in the movie lover’s mind, perhaps more than from any other of his films.” Peary asserts that “we all remember Chaplin turning bolts on the assembly line and then being unable to stop his arms from making the turning motion — he automatically tries to turn the buttons on a female worker’s dress and chases down the street a fat woman who wears a blouse with a button over each breast.” Of course “we remember him being strapped to an out-of-control feeding machine” as its operators blithely forget about the man inside being abused as it malfunctions, and we are giddy with anticipation as we watch “the blindfolded Chaplin roller-skating on a high floor in the department store, not realizing he’s close to a ledge.” Equally enjoyable are “two classic sequences in the cabaret: as a waiter he carries a tray with a duck he wants to serve an impatient customeer, but every time he nears the table he is spun to the other side of the restaurant by the many dancers on the floor;” and “debuting as a singer, he forgets the words and proceeds to sing in French gibberish, using expressions and body movements to convey that the lyrics are racy.”

What’s especially notable about this iteration of Chaplin’s Little Tramp is that “Chaplin the director-screenwriter doesn’t make it too hard on Chaplin’s character”. While his “worst moments come at the beginning in the factory”, at least “his mind is almost gone already” — and though he’s “thrown into prison several times”, it is a “sanctuary” “where he gets good treatment and is fed”. Finally, while “life is hard on the streets”, for once “Chaplin has a companion… who adores him as much as the Little Tramp adores… beautiful, unattainable women in earlier Chaplin films”. Indeed, Peary points out that the “final scene is a gem, with Chaplin (using his inimitable walk) and the lovely twenty-one-year-old Paulette Goddard… determinedly leaving the city together, hand in hand, to confront the future.”

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Fine lead performances

- A sobering look at the dangers of an overly mechanistic, anti-humanist, Big Brother society

- Numerous memorable sequences

Must See?

Yes, as a still-enjoyable classic “silent” comedy.

Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|