|

Synopsis:

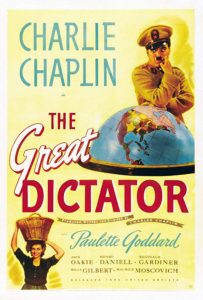

A shell-shocked Jewish barber (Charlie Chaplin) returns 20 years after World War I to his village, which is overrun by anti-semitic soldiers. He actively protests alongside a feisty maid (Paulette Goddard) he’s fallen in love with; meanwhile, their country’s tyrannical dictator, Adenoid Hynkel (Charlie Chaplin), engages in rivalty with the equally bombastic leader of neighboring Bacteria (Jack Oakie).

|

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Charlie Chaplin Films

- Comedy<

- Mistaken or Hidden Identities

- Nazis

- Paulette Goddard Films

- Rivalry

- Ruthless Leaders

- World Domination

- World War Two

Response to Peary’s Review:

Peary’s review of this controversial classic “in which Chaplin plays both a persecuted Jewish ghetto barber in Tomania and that country’s power-mad dictator” shows evidence of his conflicted feelings. He writes that a few years after the film’s release, “Chaplin expressed regret that he’d made this film a comedy because he then realized how naive he’d been about the whole political situation in Germany”, and “at the time, he didn’t know about what was actually taking place in concentration camps, or about the impossibility of any resistance to SS troops, or about the absurdity of suggesting Hitler’s ouster, or about the extreme brutality of Hitler’s vision”. Peary adds, “Despite Chaplin’s correct reservations about the film, it’s still a joy to watch Hynkel/Hitler tumble down a flight of stairs, or have Benzino Napolino (Jack Oakie), dictator of Bacteria, toss peanut shells on him, or act the buffoon as he fantasizes about world conquest — climbing up his curtains and bouncing a balloon globe off his rump while in the paroxysms of … ecstasy”. In his Alternate Oscars, Peary doesn’t nominate this as one of the Best Pictures of the Year (unlike the actual Academy), though he retains Chaplin’s nomination as one of the Best Actors of the Year.

Unlike Peary, I don’t believe Chaplin needed to make excuses for crafting this highly effective satire, which strikes me as akin to To Be Or Not to Be (1942) turned up a notch. With that said, according to TCM’s Behind the Camera article:

As the premiere approached, Chaplin had good reason to be concerned about his gamble on political commentary. Gallup polls revealed that 96 per cent of Americans opposed U.S. involvement in the war in Europe, and threatening letters from Nazi sympathizers poured into the studio. At one point he even asked a friend with the Longshoreman’s Union in New York if they could have some union members present at the opening to prevent a pro-Nazi demonstration.

Chaplin makes his open disgust for both Hitler and fascism clear in multiple ways throughout the film. As James Hendricks notes in his review for Q Network:

With the exception of a few notable German words and phrases, most of what Hynkel says is pure nonsense, which is a direct literalization of Chaplin’s view of fascist politics. And that, ultimately, is what The Great Dictator demonstrated to the world, undercutting hatred and totalitarianism by revealing them to be the strained devices of desperately pathetic and insecure men.

Unfortunately, this film remains highly relevant in our climate of political bromances between world leaders — indeed, the best scenes are those between Chaplin-as-Hynkel and Oakie-as-Napolini. I’m less enamored with the narrative thread about The Barber’s romance with Goddard, though it serves its purpose well and leads us towards the highly contested final six minutes of the film. As Peary notes, “this was Chaplin’s first talkie for a reason — he wanted audiences to hear the difference between Hitler’s words of madness (they’re unrecognizable, he’s shouting so strongly)… and Chaplin’s own clear words of sanity and reason, delivered in a speech by the barber (who’s passing as Hynkel), which call for brotherhood and peace.” I disagree with critics who feel the speech is overbearing and interrupts the film’s flow; it’s actually a perfectly fine ending to a movie that serves as both a satire and a serious call to awareness and action.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Charlie Chaplin as Hynkel

- Jack Oakie as Napolini

- Many memorable sequences

Must See?

Yes, for its historical relevance and still biting satirical wit. Named to the National Film Registry in 1997.

Categories

Links:

|

One thought on “Great Dictator, The (1940)”

First viewing (surprisingly). A once-must for its historical relevance – though, as a film, I have to say it’s a mixed bag.

Over the years, I’ve seen a clip from this film here and there when it was referenced for some reason. I also knew that, to a degree, people criticized Chaplin for (consciously or not) making light of Hitler.

Chaplin only sometimes makes Hitler out to be a complete idiot – and sometimes that’s done cleverly when he has Hitler’s own words turn on him (“He’ll deal with a medieval maniac more than he thinks!”). But there are perhaps all-too-numerous times when the humor is venom-free, lighthearted and tentative (i.e., when Hitler occasionally finds a quick moment to run into a room where a painter and a sculptor are on-call as he poses for them and for posterity). It’s at such times that we can believe Chaplin’s confession that he was naive. Would he even have made this film at all had he known more at the time?

Still… if we look at our own time… and our own maniac that we’re dealing with… that idiot has caused havoc, destruction and death (more than is reported) and every day on facebook, people take Chaplin-like stands in the way they mock what I refer to as ‘The Thing’. So the impulse is the same: to make a clown out of a (deranged) clown.

‘TGD’ remains in part a film that has not aged well in terms of its humor. Sections of it are overdone or slapstick-happy – or they’re done strangely (why, for instance early on, is the upside-down plane suddenly illogically placed right-side-up for the audience when doing so kills the comedy?).

But other sections remain strong: the long sequence of the coins hidden in the pudding is inspired. As well, all of Chaplin’s scenes with Reginald Gardiner and Henry Daniell (both cast perfectly as Schultz and Garbitsch) work wonderfully.

Personally, I find the film’s last 5 minutes quite moving. In fact, in a way, they just about justify the entire film – since the film’s heart longs to be strong in the right place.