|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Falsely Accused

- Historical Drama

- Horror Films

- Michael Reeves Films

- Morality Police

- Revenge

- Vincent Price Films

- Witches and Wizards

Response to Peary’s Review:

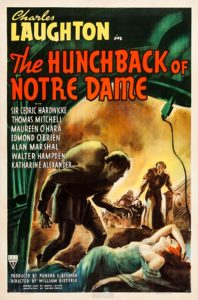

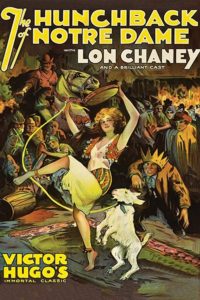

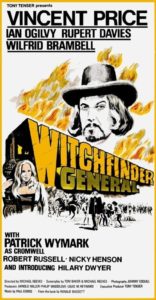

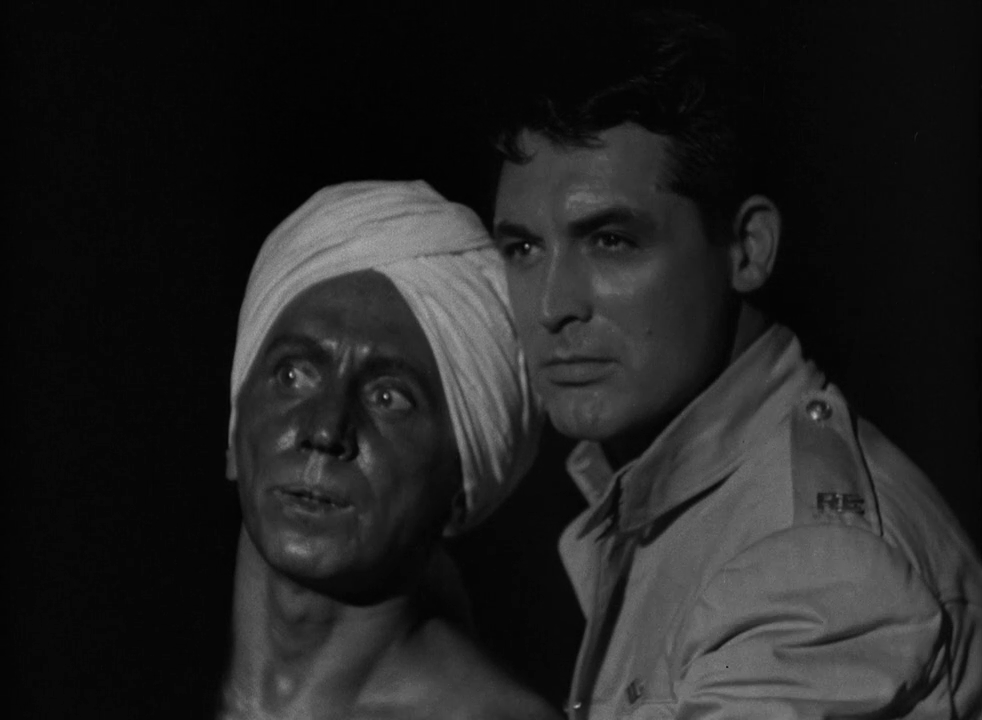

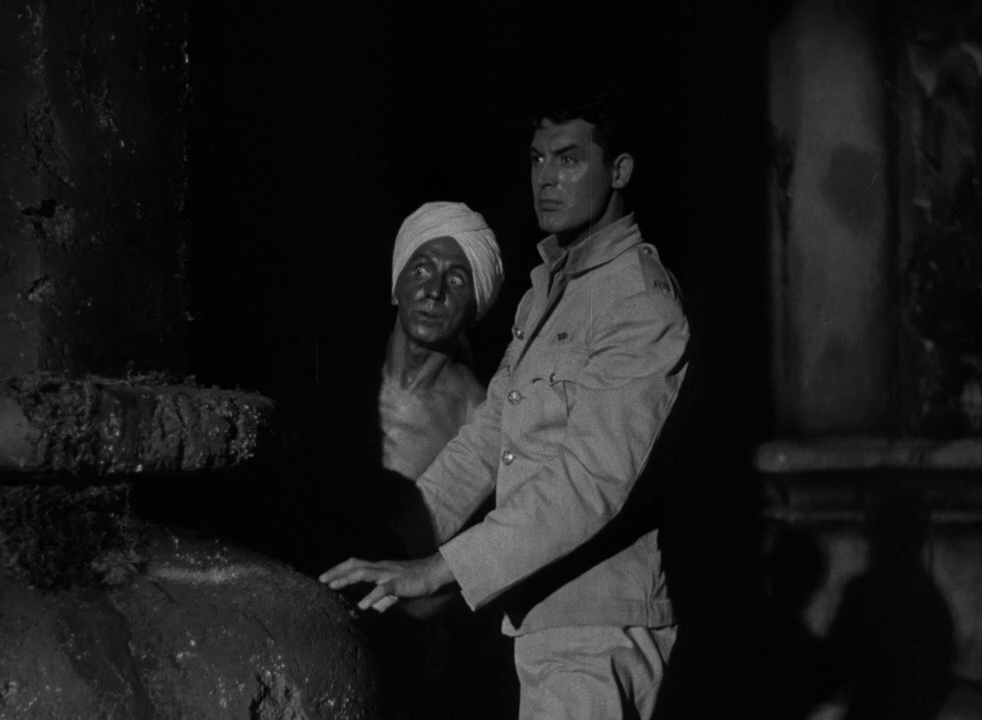

Peary writes that this “brutal, visually and thematically fascinating cult film by the controversial Michael Reeves” — “his last work before his death at age twenty-five” — shows that “his talent as director and writer was indisputable and his condemnation of those who lust for and abuse power admirable”. He points out that the evil in this film “is all-encompassing, as is evident when Hopkins kills suspected heretics in fire, in water (by drowning), and in the air (by hanging)”. Price — playing an “angel of death” — “has never been better”, portraying “a menacing, brutal, shrewd, arrogant puritan on a black horse who conveys the scorn that a man of Hopkins’s breeding would have for a world that financially rewards him for committing monstrous acts”: he “debases… people by raping their women, taking their money, and executing those brave enough to protest.” Peary reminds us that this film is “not for the squeamish, but [nonetheless] a powerful, one-of-a-kind film”.

Peary’s GFTFF review is lifted directly from his lengthier Cult Movies essay, where he contrasts this horror film (based in name only on a poem by Poe) with “all those enjoyable Poe films starring Vincent Price, like The House of Usher (1960), The Pit and the Pendulum (1961), and The Masque of the Red Death (1965)“, which were “intentionally claustrophobic, with almost everything taking place within secluded castles”, and evil — as “personified by the mad, hermitlike Vincent Price characters” — “confined to the castles themselves, so that if the castles are destroyed the evil within their walls will be destroyed as well.” In The Conqueror Worm, on the other hand, we “are presented with an evil that is overwhelming, invulnerable, and that will emerge victorious” — it is “not confined to a single castle but runs rampant across all of England, contaminating the people, wiping out whatever goodness exists and replacing it with a contagious sickness characterized by each ‘victim’s’ desperate need to be cruel to his fellow human beings.”

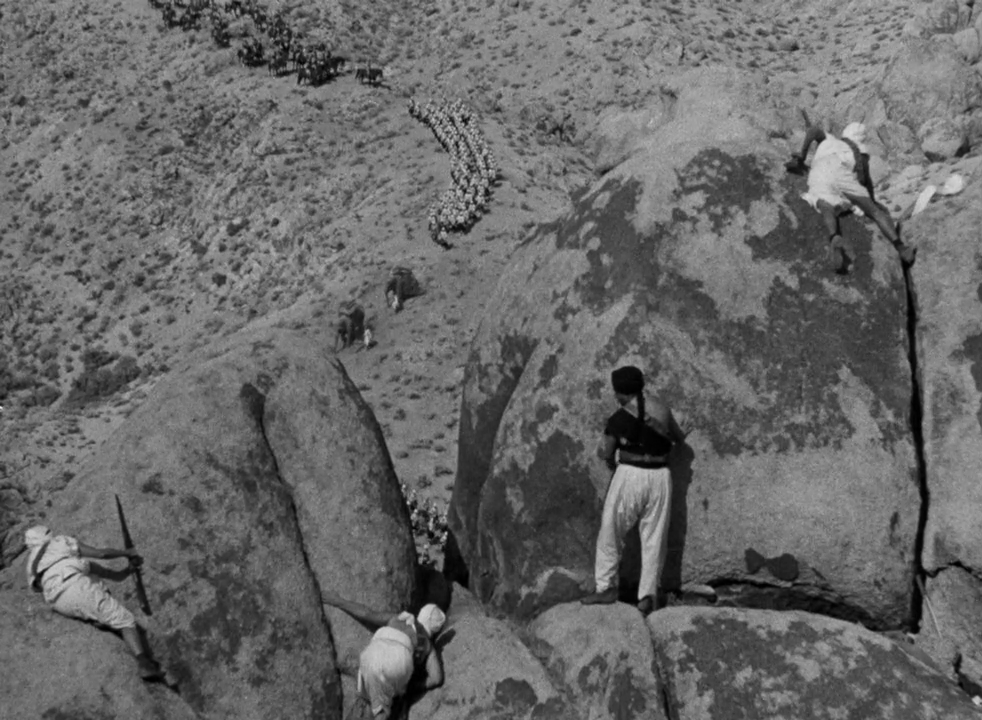

Peary adds that two of Reeves’ greatest achievements with this film — his third and last after The She Beast (1961) and The Sorcerers (1967) — were managing “to keep Price from going into the ham actor routine that mars many of his performances”, and for keeping narrative tensions consistently high. He points out that the film starts with a “pre-credits sequence so powerful — a screaming woman being led to a scaffold where she is hanged — that the film must be kept at a high level of intensity in order to avoid a dramatic letdown”, but notes that Reeves is successful in maintaining “an extraordinary momentum throughout”. Viewers should be forewarned that “along the way there is much violence — executions, tortures, a nerve-wracking soldier-ambush sequence” — and “whenever there is a chance that the hectic pace might be slowing a bit, Reeves automatically has Marshall [Ogilvy] jump on his mighty steed and race it across the countryside”, thus never giving the audience “a chance to relax”. I agree with Peary’s closing statement that “by the end of the film it is as if you have just run the gauntlet”.

With that said, this film’s relentless violence has a (sadly relevant) purpose, showing how easily mankind can descend into joy of torture — or at least mindless acceptance of it as commonplace and necessary. Reeves includes plenty of tracking shots showing villagers calmly watching as “witches” are burnt to death; minor facial expressions demonstrate that they likely believe the heretics deserve their fate.

Also of note is the film’s gorgeous cinematography, showcasing real-life horror taking place in an atmospheric landscape of Gothic forests, meadows, village squares, and dank interiors. With his expert directorial hand, Reeves makes powerful visual statements throughout: for instance, as Ogilvy comes back to Dwyer and listens to her “confession” about what she’s done to try to save her uncle, she is framed by the word “WITCH” scrawled on the wall of a church behind her — but when Ogilvy brings her down to her knees with him to pray and ask God to marry them, the term neatly disappears from our view. In another notable instance, crashing waves at the seashore (freedom) turn into the fiery flames that will put an innocent victim to death. Reeves’ film is both brutal and brilliant, a worthy culmination to his far-too-short career.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Vincent Price as Matthew Hopkins (nominated as one of the Best Actors of the Year in Peary’s Alternate Oscars)

- Johnny Coquillon’s cinematography

- Strong direction throughout

Must See?

Yes, as a justifiable cult favorite.

Categories

Links:

|