|

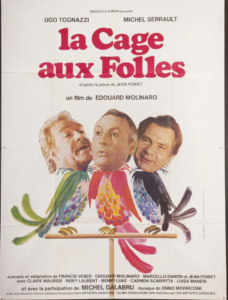

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Comedy

- French Films

- Gender Bending

- Homosexuality

- Mistaken or Hidden Identities

- Morality Police

- Nightclubs

- Play Adaptation

Response to Peary’s Review:

Peary is clearly no fan of this “French farce” which “became the most successful foreign film ever to play in the U.S., raking in more than $40 million and playing in some theaters for more than a year.” He notes that given how “it caused so much excitement among those who loved it or despised it”, it’s “startling how innocuous it is;” he goes on to refer to it as a “dishonest film” that is “so timid it suggests that this gay couple could raise a heterosexual son — and a boring son at that” (?!?).

He’s right to point out that the film “plays it [too] safe, catering to straight audiences” to the extent that the only “lovemaking scene” we see “involves [Tognazzi] with a female, his ex-wife”.

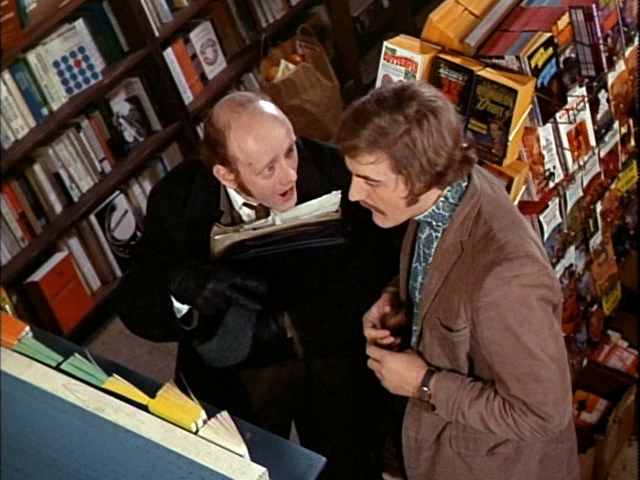

He also points out that much of the film’s “humor comes at the gay characters’ expense; repeatedly we are supposed to laugh at how effeminate [Serrault] and butler Jacob [Benny Luke] are, at how exaggerated their mannerisms are, at how awkward they look when walking or gesturing, at how affected their voices are … , and how they whine or scream in surprise over everything.”

Unfortunately, “director-co-writer Edouard Molinaro never bothers to explore the subtleties of his characters or accentuate their endearing idiosyncrasies”: Tognazzi “tolerates [Serrault] in [a] conventional movie fashion — like a husband who accepts the childish activities and personality of his wife because she is female and is supposed to act that way;” and “there are surprisingly few funny moments in the major sequence in which [Tognazzi] and [Serrault] try to clean up their act when [Tognazzi’s] son brings home for dinner his fiancee, her mother, and her father… who is the secretary for the Union of Moral Order.”

Peary argues that while “there’s potential for fireworks”, “Molinaro forgot the matches”. He rags further on the film in his Cult Movies book, where he states that “Molinaro has no flare for comedy and never lets a scene run long enough for the gags to develop sufficiently.”

Peary does concede that there are at least “several amusing moments in the picture”, including “when [Tognazzi] toasts [Maneri] over the phone by breaking a glass on the receiver;” “when [Tognazzi] instructs [Serrault] how to butter his toast and stir his tea in a masculine manner;” and “when [Scarpitta] and [Serrault] quibble over whether the nude figures on the dinner dishes are all boys, as [Scarpitta] insists, or are male and female, as [Serrault] fibs.”

Ultimately, however, Peary dismisses this film as “a family comedy that never rises above a level of mediocrity” — as “rollicksome as the most tired French bedroom farce but not as risque, as stupid a Laura Antonelli sex comedy but not as arousing, and as ‘controversial’ and ‘relevant’ as Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? (1967) is today.”

While I enjoyed this “innocuous” cult comedy more than Peary, I agree with many of his assessments. It’s weird — though perhaps not surprising, given the intended audience — that Tognazzi allows himself to be “seduced” by Maurier (perhaps this was done to “prove” that Laurent could have been conceived once upon a long time ago?), and much of the humor-at-the-expense-of-homosexuality comes across as terribly dated these days. How much you laugh may depend on how much you can simply giggle uncomfortably — something that’s NOT possible in any way with Luke’s portrayal of a servile black “maid” (everything about how his character is presented and treated rings distasteful).

With that said, I think all film fanatics should watch this film once to become familiar with it, though it likely won’t become a repeat favorite.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Michel Serrault as Albin

Must See?

Yes, once, for its cult status.

Categories

Links:

|