|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Historical Drama

- Royalty and Nobility

- Russian Films

- Ruthless Leaders

- Sergei Eisenstein Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

Peary writes that “this continuation of Sergei Eisenstein’s epic about Ivan IV… is more stylized than Part I” given that he “uses color at times, and he has [his] characters sing.”

However, he argues this “doesn’t help” the movie, noting that he’s “never seen so many people in a theater dozing off as when [he] last saw this film.” While he concedes the movie is “beautifully shot,” he also notes that it’s “slow-moving and lacking some of the pivotal characters of the first part.”

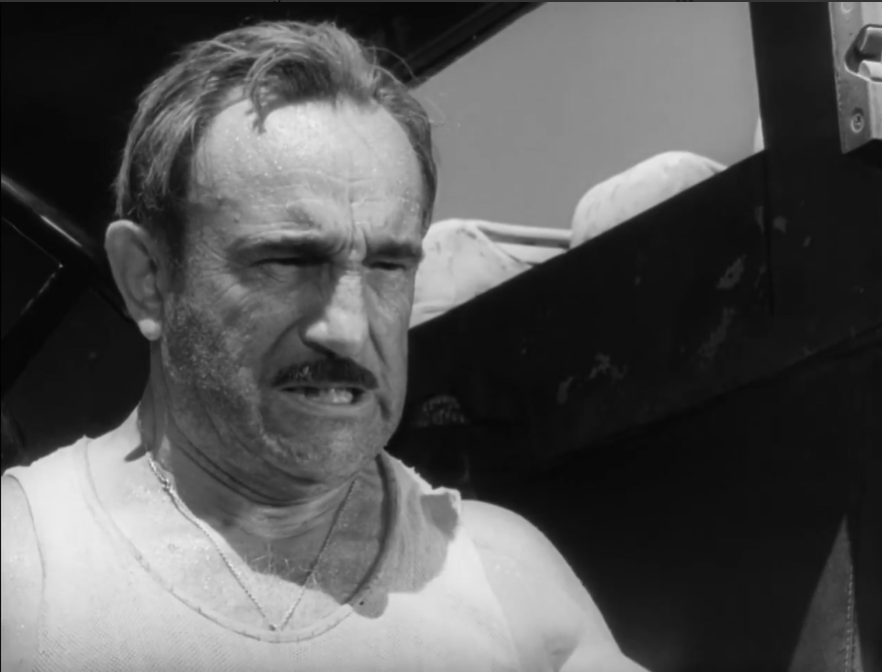

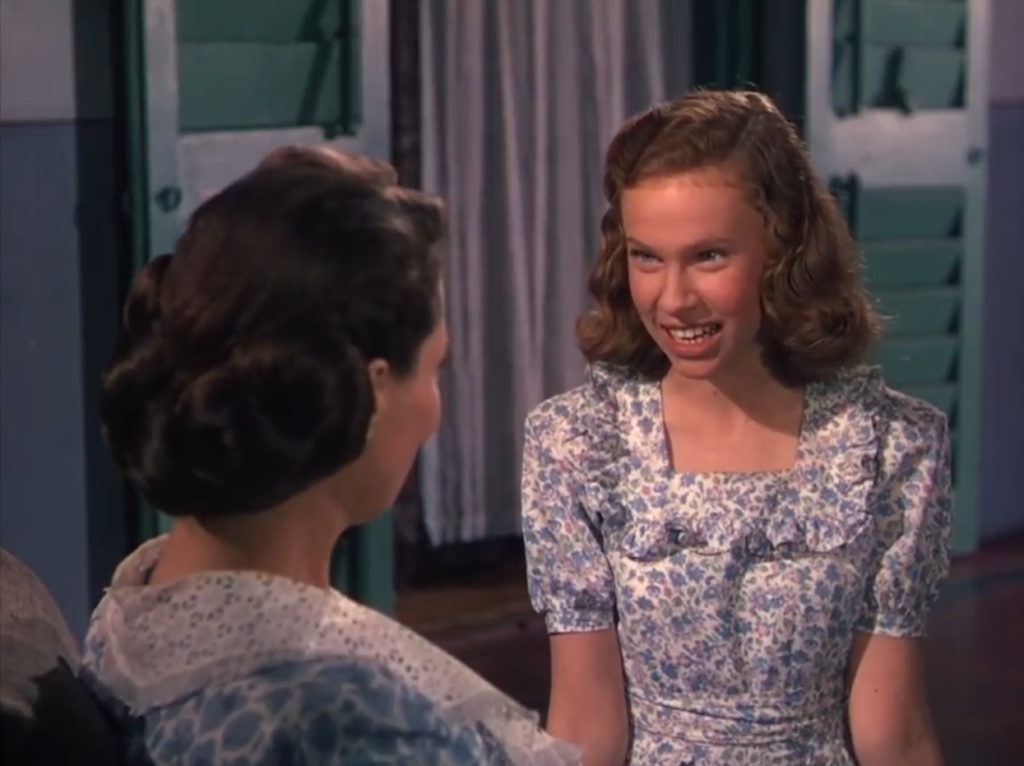

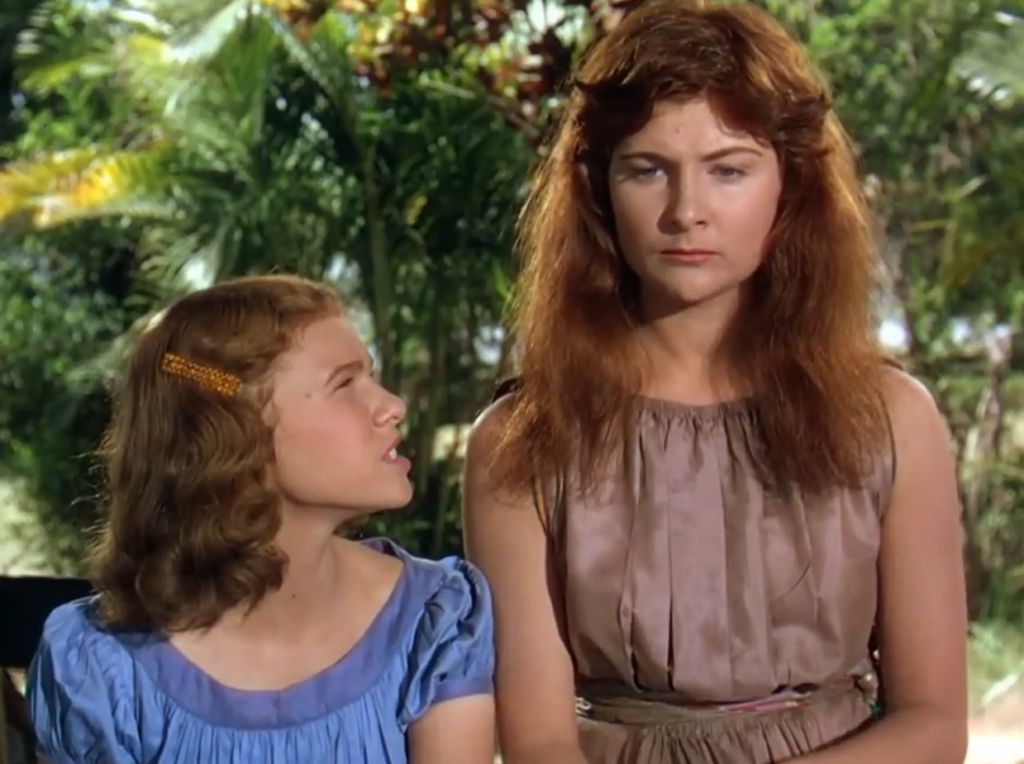

I actually don’t agree with Peary: while I share his sentiment that Part I is “ludicrously melodramatic” and over-rated, there’s a lot going on this time around, with the storyline heading in a more interesting (and dangerous) direction — and we definitely see “pivotal characters” from the first movie, most notably Aunt Efrosinia and her son, who is as infantilized as ever but now has the beginnings of a beard:

In Part II we’re given better insight into Efrosinia’s naked ambitions (“I’d suffer the pangs of your birth a hundred times over to see you seated on the Tsar’s throne!”), and we actually begin to feel compassion for idiotic Vladimir, who pitifully asks, “Why are you always trying to make a leader of me, mother?” To that end, the “lullaby” Efrosinia sings to Vladimir is appropriately creepy:

A black beaver was bathing in the river,

in the frozen Moscow River.

He didn’t wash himself cleaner;

he only got blacker.

Having taken his bath, the beaver

went off to the capital’s high hill

to dry himself, shake himself, and look around,

to see if anyone was coming to look for him.

The hunters whistle, searching out the black beaver.

The hunters follow the scent:

they will find the black beaver.

They want to catch and skin the beaver,

and with its fur then to adorn a kingly mantle

in order to array Tsar Vladimir!

The final sequence — involving carefully crafted deception and violence — really jolted me, making me realize how invested I’d become in this scenario.

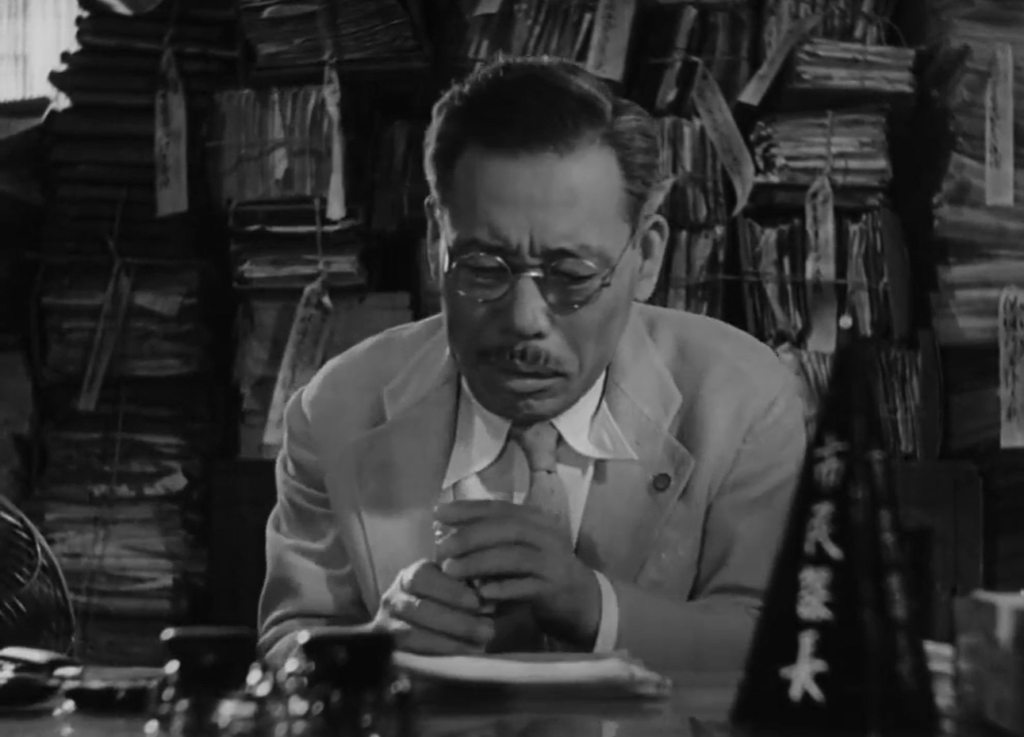

Meanwhile, the early inclusion of a flashback sequence showing the trauma young Ivan experienced when his mother was brutally killed by boyars helps us to better understand his enduring hatred for them:

It’s too bad that Eisenstein passed away before he was able to complete the intended third portion of this epic, given that he was going to continue to build on Ivan’s paranoia. Peary writes that “obviously, Eisenstein’s czar is meant to represent Stalin’s view of himself” — and this time around, that makes a lot more sense.

Note: Putting an accurate date on this film is tricky; Peary lists 1945, but I’ve put 1958 given the following information (from Wikipedia): “Part II, although it finished production in 1946, was not released until 1958, as it was banned on the order of Stalin, who became incensed over the depiction of Ivan therein.”

Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

- Atmospheric cinematography and memorable imagery

- Sergei Prokofiev’s score

Must See?

Yes, as the powerful second part of Eisenstein’s final work.

Categories

- Historically Relevant

- Important Director

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|