Raisin in the Sun, A (1961)

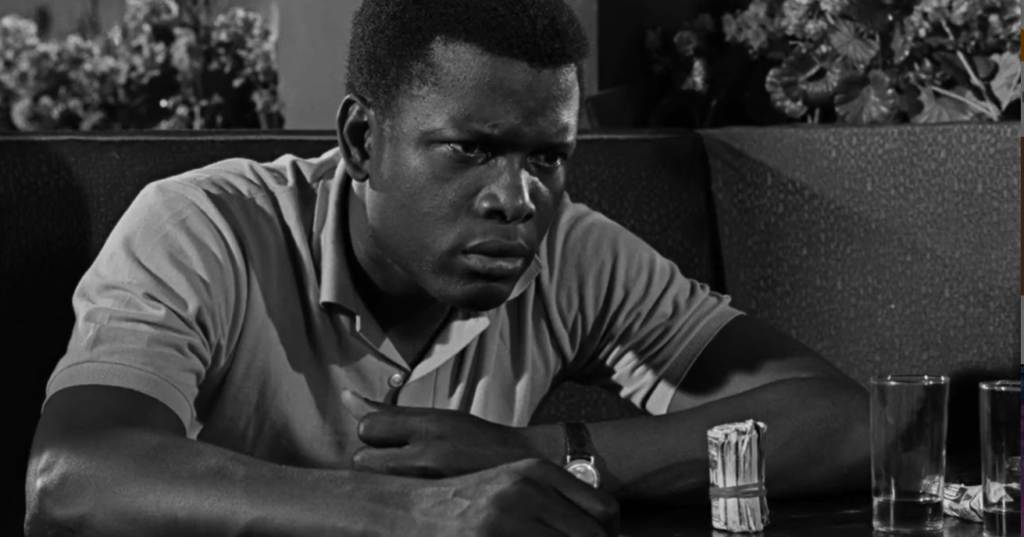

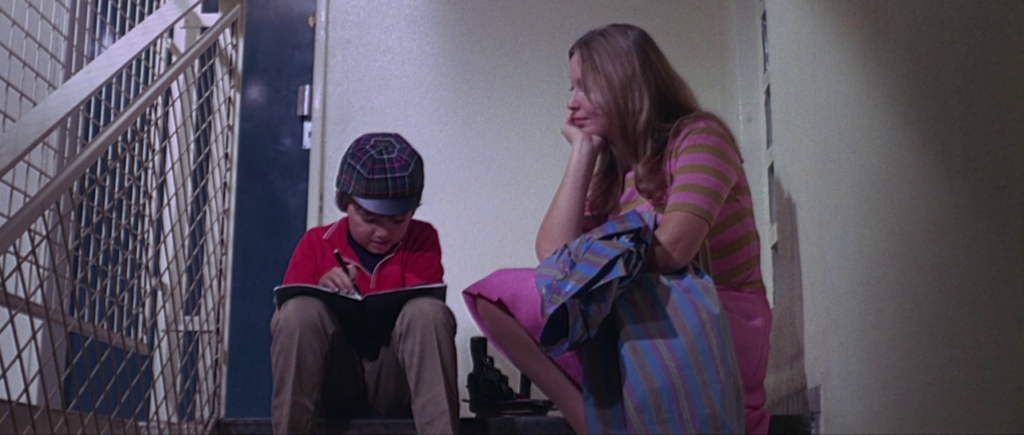

“I’m lookin’ in the mirror this morning and I’m thinkin’, I’m 35 years old, I’m married 11 years, and I got a boy who’s got to sleep

in the living room because I got nothin’ — nothin’ to give him but stories like on how rich white people live.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

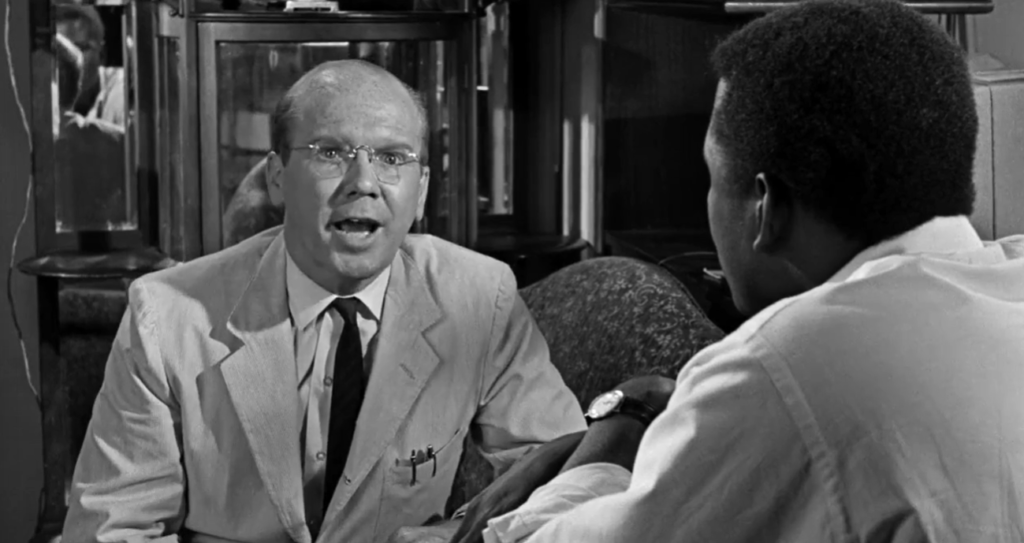

Review: It’s heartbreaking to watch each of these characters grappling with challenging constraints, and see the pressures that inevitably arise within a landscape of limited funds and diverse ideas of how to achieve success and happiness. The toxicity of societal racism comes through loud and clear, with John Fiedler’s representative from the “Clybourne Park Improvement Association” (in the family’s intended new neighborhood) embodying the sniveling “new” format through which racial intolerance is communicated. Authentic tension abounds through each of the interwoven narrative sub-strands, ranging from Poitier’s desperate desire to finally break free from his job as a chauffeur and work for himself, to Dee’s angst over bringing a new child into their family, to McNeil’s determination to provide a home for her family, to Sands’ indecision around who to date: her well-to-do suitor George (Louis Gossett Jr.) or a Nigerian classmate (Ivan Dixon) who entices her with visions of exploring her cultural heritage. This engrossing, finely-acted film — which was selected by the Library of Congress in 2005 for preservation in the United States National Film Registry as being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” — remains well worth a look. Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

Must See? Categories

Links: |