|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Class Relations

- Dancers

- John Travolta Films

- New York City

- Social Climbers

- Womanizers

Response to Peary’s Review:

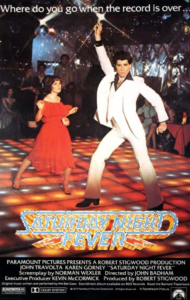

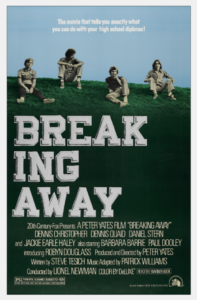

As Peary writes, “John Travolta danced the disco beat to instant superstardom in this smash hit” in which he “plays 19-year-old Tony, who lives in a lower-middle-class Catholic neighborhood in Brooklyn” and on “Saturday nights” is “top dog at the local disco.”

Indeed, “dancing gives him his only fulfillment” — though “he senses that it can’t last forever,” and “across the bridge is Manhattan — the promised land.”

Peary asserts that the movie’s theme “is that every person has the talent to ‘make it,’ to escape the neighborhood where there are no opportunities; all anyone needs is drive and opportunities” — and for “Travolta and Gorney, opposites who get serious about each other,” the “disco’s upcoming dance context [is] their springboard to the big time.”

Unfortunately, the “film is shallow,” but Peary argues that “Travolta is electrifying, whether getting dressed in his room, wiggling down the street:

… trying desperately to express himself in conversation, making love, or, of course, putting on an amazing display on the dance floor.” He adds that the “disco score, featuring popular Bee Gees songs, is super,” and points out that the film is “stylishly, feverishly directed by John Badham, who isn’t ashamed to explore Travolta’s sexual appeal.”

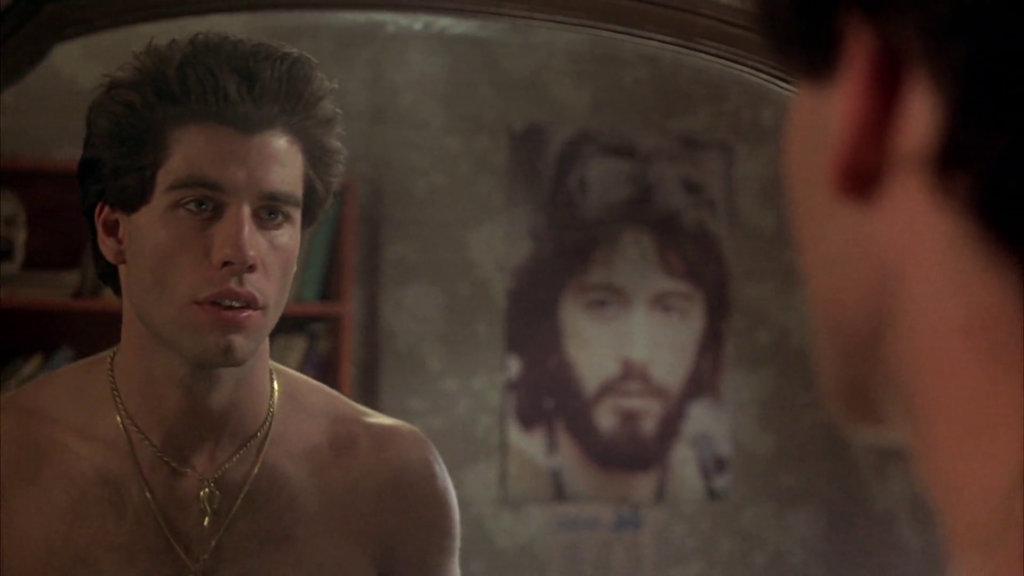

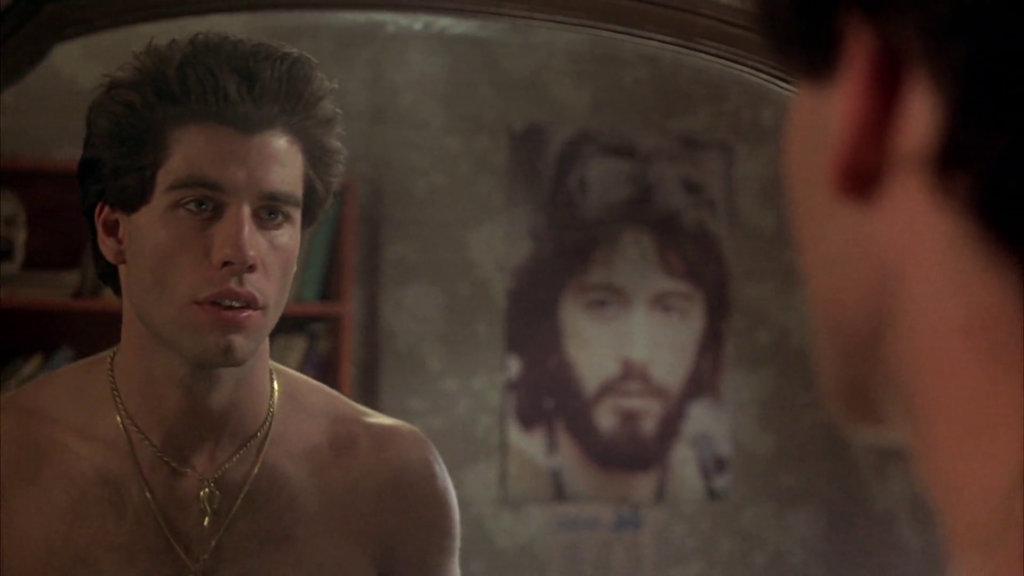

Peary elaborates on Travolta’s breakthrough big-screen performance in Alternate Oscars, where he names him Best Actor of the Year and writes: “There was doubt that Travolta could make the transition from television, where he’d built up a following as Vinnie Barbarino in the high school comedy Welcome Back, Kotter.” However, “in his first movie lead (he’d been funny in a secondary role in Carrie) he became the sensation of the year, a magazine cover boy and sex symbol.” He points out that Travolta — who is “captivating” — is “great out on the dance floor, making sexual moves to the Bee Gees that have the females in the 2001 [Club] sighing:

… but he’s just as much fun to watch while strutting down the street as if he knows everyone is watching, or gazing at himself in the mirror — a moment of narcissism for a young boy without much self-esteem.”

He highlights how Travolta “has sweet, puppy-dog eyes, a sheepish face, and a delivery that starts out aggressive but ends up sounding hurt or defensive, as if he expects to be put down”; and he smiles “appreciatively if he gets a compliment, as when his boss gives him a raise:

… and when Stephanie [Gorley] admits he’s interesting and even intelligent.”

In his review for DVD Talk, Stuart Galbraith IV argues that:

The movie benefits from an almost classical script rich in characterizations. I was impressed by how in the movie tells us so much about Tony in just the first two minutes. Before the end of the first reel the audience learns Tony: likes to chase women, is a kind and thoughtful brother, is trusting and kind-hearted to strangers, thinks fast on his feet, and is popular in his neighborhood. The posters in his bedroom say it all — on the walls are Bruce Lee, Farrah-Fawcett, Rocky, and Al Pacino (as Serpico).

Interestingly, in the original magazine article upon which this script was based — later acknowledged by the author to be made up — the lead character (here named Vincent) daydreams explicitly of disturbing violence.

… Whenever he gazed into the mirror, it was always Pacino who gazed back. A killer, and a star. Heroic in reflection. Then Vincent would take another breath, the deepest he could manage; would make his face, his whole body, go still; would blink three times to free his imagination, and he would start to count.

Silently, as slowly as possible, he would go from one to a hundred. It was now, while he counted, that he thought about death.

Mostly he thought about guns. On certain occasions, if he felt that he was getting stale, he might also dwell on knives, on karate chops and flying kung fu kicks, even on laser beams. But always, in the last resort, he came back to bullets.

Fortunately, this isn’t how Tony is portrayed on-screen — though his buddies’ crude and immature behavior is often challenging to watch, as is Tony’s rejection of his original dance partner (Donna Pescow), who is eventually subjected to highly disturbing treatment.

Indeed, women aren’t exactly portrayed in the best light in this film. While Gorney — who Peary claims “can’t act” — refreshingly stands up for herself time and again, she’s referred to repeatedly as “practicing to be a bitch” and is given a hard time for being a “social climber.” Other young women (i.e., Denny Dillon’s “Doreen”) clamor to dance with, sleep with, or simply be nearby Tony:

… while the women back at home (Tony’s mother and grandmother) merely fuss over food or show deep distress when Tony’s priestly brother (Martin Shakar) has a career crisis.

Another subplot — involving neurotic Bobby (Barry Miller), who has gotten his girlfriend pregnant and is seeking advice from everyone around him on what to do — is intentionally meant to mirror James Dean and Sal Mineo’s relationship in Rebel Without a Cause (1955), though in a less nuanced and more distributed way.

Ultimately, Saturday Night Live is a film to watch for Travolta’s dynamic performance and as a snapshot of a certain era — not because of any particularly profound insights it offers into the human condition. Be forewarned that you will get “Night Fever” stuck in your head for hours (if not days) after watching this flick.

Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

- John Travolta as Tony

- Excellent use of location shooting across the city

- The Bee Gees’ iconic score

Must See?

Yes, for Travolta’s performance and its historical significance.

Categories

- Historically Relevant

- Noteworthy Performance(s)

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|