|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Comedy

- Hollywood

- W.C. Fields Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

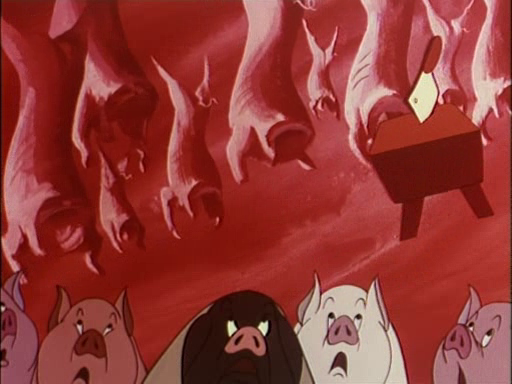

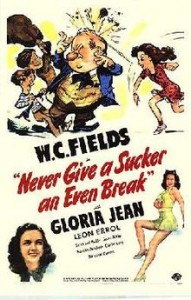

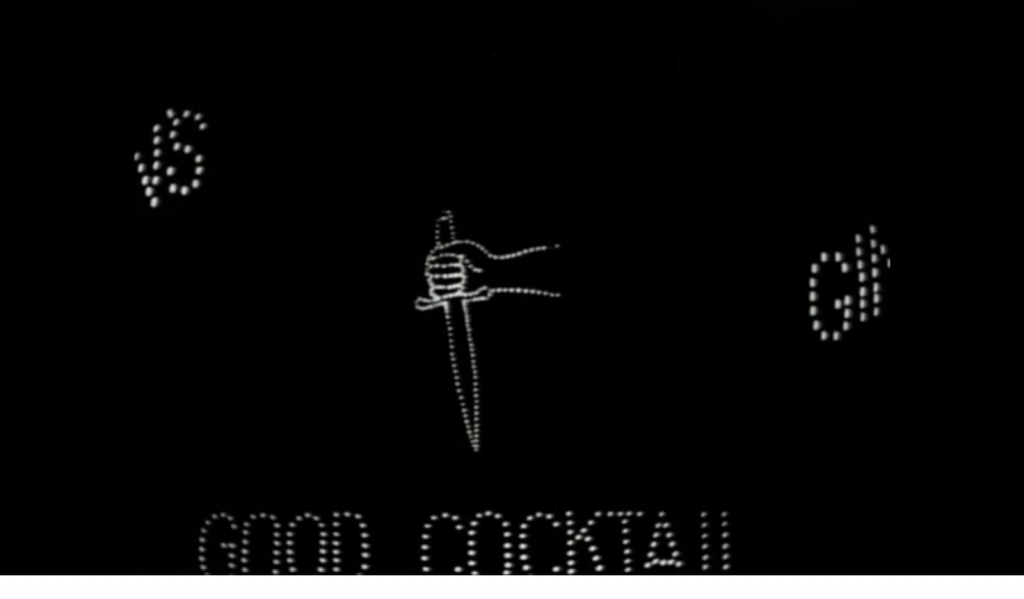

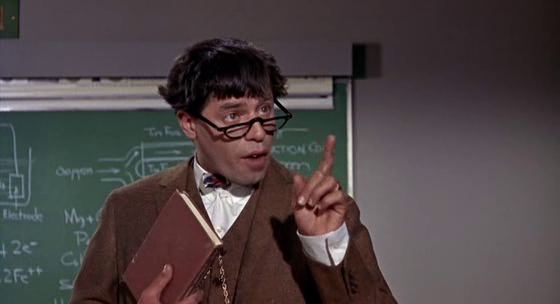

Peary argues that this “last starring role” for W.C. Fields isn’t “top-grade Fields because he isn’t on-screen enough…, he isn’t bombastic or aggravating enough, and he isn’t being constantly harassed by the nincompoops that usually populate his films” — but I have to say I disagree. While Fields might not be on-screen continuously, his presence as screenwriter (writing under the typically creative pseudonym of Otis Criblecoblis) is fully felt throughout, to joyfully surreal effect. Indeed, Peary does acknowledge that this is “the film where the surrealistic nature of Fields’s comedy is most evident”, given that the film-within-the-film (pitched by Fields to an exasperated Franklin Pangborn; what brilliant casting!:

transpires in a fantastical alter-universe: Fields is traveling with his niece, Gloria Jean, on an airplane, when suddenly he “leaps… to retrieve his whiskey bottle and falls thousands of feet before landing safely on Margaret Dumont’s mountaintop estate, where she lives with her pretty young daughter:

… a gorilla:

… and [a] Great Dane with fangs”:

… and later arrives at a Russian village in Mexico (!).

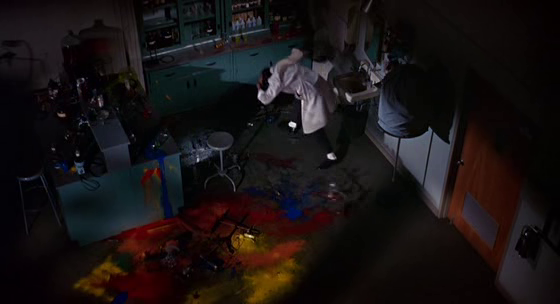

Truly, the preposterous scenario proposed by Fields — which Pangborn, naturally, rejects as “impossible, incomprehensible, inconceivable; and besides that, it’s no good” — seems to be the loopy product of both Fields’s accumulated years of experience on wackily hybrid studio sets (viz. the film’s opening sequences), and his constant inebriation, which is referenced continually throughout both the meta-narrative and the fantasy film. In one classic scene, for instance, Fields enters “an ice-cream parlor, where, before blowing the head off his ice-cream soda, he turns to us to reveal that censors wouldn’t let him stage the scene in a saloon”. Within the fantasy film, numerous laughs are milked (sorry) when Fields shares a stiff drink of goat’s milk (!) with an engineer (Emmett Vogan):

Fields would find intoxicating substances under a rock if necessary, it seems.

At any rate, your enjoyment of this film will ultimately depend upon how much you’re willing to forgo straightforward narrative in favor of something much more — dare I say, post-modern? Rewatching it again last night, after viewing and posting on numerous “pure” Fields films, I find myself enjoying it perhaps most of all, simply for its perversely illogical and “messy” status. Knowing in hindsight that this was to be Fields’s final starring role, it could be viewed as an especially apt “sayonara” — i.e., Fields’s attempt to throw everything plus the kitchen sink into his grand finale. At the same time, as Dave Kehr notes, the film “has an appealingly inward, mournful quality, as if it were a swan song that only its singer could hear. Unconcerned with reaching the audience, Fields seems to be muttering to himself through much of the movie, his barely audible remarks often achieving a strange poetry: ‘The chickens lay eggs in Kansas. The chickens have pretty legs in Kansas.'”

Note: My single favorite moment (over in an instant): Franklin Pangborn, agitatedly trying to help Gloria Jean rehearse, is momentarily caught up in a male chorus line dancing through the studio.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See?

Yes, as a truly surreal comedic effort — and for its historical relevance as Fields’ last film.

Categories

- Good Show

- Historically Relevant

Links:

|