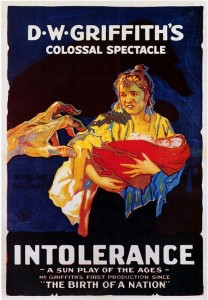

Intolerance (1916)

“Our play is made up of four separate stories, laid in different periods of history, each with its own set of characters. Each story shoes how hatred and intolerance, through all the ages, have battled against love and charity.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

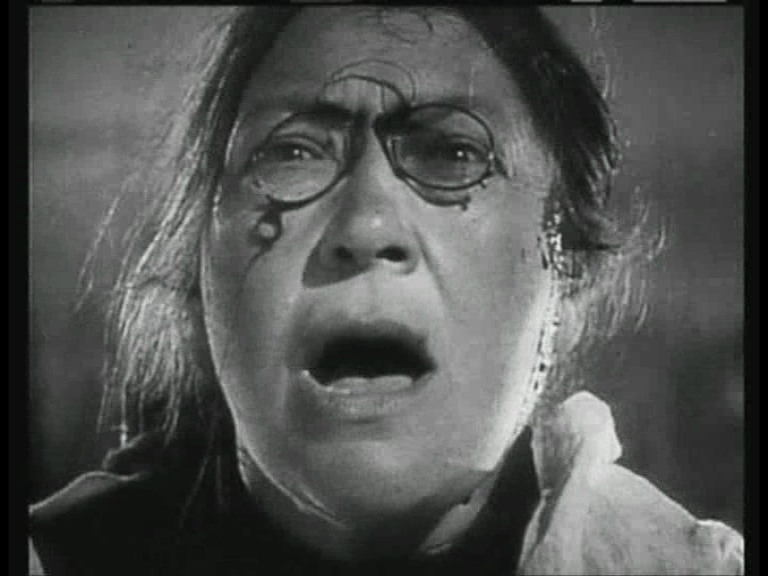

Response to Peary’s Review: With that said, there’s no denying that this three-hour-long silent movie will, for most ffs, feel like a bit of a long haul to get through. While Peary’s only complaint about the film is that Griffith’s “theme of ‘intolerance’ is a feeble link between the episodes” (he notes that Griffith “seems passionate only about the modern story”), I would argue that Griffith’s overly pedantic presentation style comes across as terribly dated throughout, and will be off-putting to most young ffs. Meanwhile, his groundbreaking attempt to weave numerous stories together has the unfortunate side effect of shifting our attention away from each scenario just as we’re beginning to make sense of it (and the characters). Indeed, despite its undeniable historical value, it’s difficult for me to agree with Peary that “this film has greatness written all over it”, simply given that it doesn’t touch me on an emotional level. I’m ultimately much more aligned with the sentiment of Time Out’s reviewer, who argues that despite the film’s “overwhelming” “visual poetry”, its “thematic approach no longer works”, and the “title cards are [both] stiffly Victorian and sometimes laughably pedantic”. As Chris Edwards argues in his “Silent Volume” blog, Intolerance “is not a silent film for someone new to the medium.” Of special interest, however, is what Time Out’s reviewer refers to as “the unbridled eroticism of the Babylon harem scenes”, which “demonstrate just what Hollywood lost when it later bowed to the censorship of the Hays Code”; indeed, these scenes are presented with such surprising casualness and lack of moral approbation that one can’t help feeling a renewed respect for Griffith’s sensibilities. Meanwhile, the enormously expensive, expansive sets truly are astonishing, and the lengthy recreation of a Babylonian battle is especially impressive in its rigor and attention to detail. I’m also fond of Mae Marsh’s performance as the female protagonist of the modern episode, playing a young woman whose falsely accused husband (Robert Harron) simply can’t seem to get a break in life; while her travails are presented in an overly melodramatic fashion, we remain fascinated throughout by her uniquely expressive face. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |