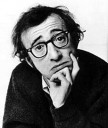

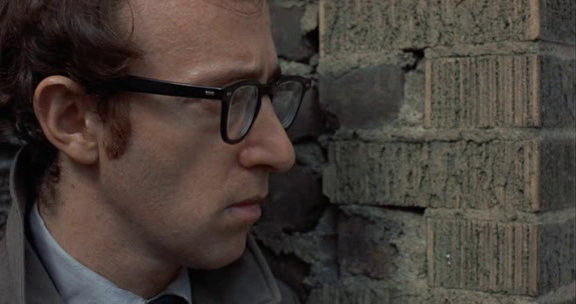

I’ve now posted on all 18 of the Woody Allen titles listed in Peary’s GFTFF — which happens to cover every single feature he directed (and/or starred in) up to the time of the book’s release. Interestingly, I’m voting all but one as “Must See” — providing evidence either of Allen’s indisputable genius during the first half of his lengthy career, and/or my personal fondness for his work:

I’ve now posted on all 18 of the Woody Allen titles listed in Peary’s GFTFF — which happens to cover every single feature he directed (and/or starred in) up to the time of the book’s release. Interestingly, I’m voting all but one as “Must See” — providing evidence either of Allen’s indisputable genius during the first half of his lengthy career, and/or my personal fondness for his work:

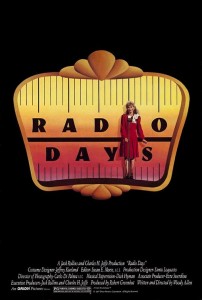

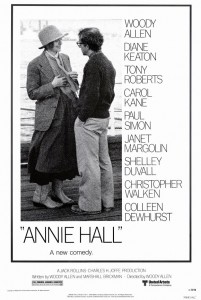

For Allen fans, it’s nearly impossible to pick a favorite title from the above list, or even a few favorites, given that so many of his earlier movies delight on a variety of different levels. Like many others, I have a personal fondness for Annie Hall (it’s probably the Allen title I find most consistently clever, enjoyable, and romantic) — but I also wouldn’t want to live without repeat visits of Sleeper or Zelig (close runners-up). Manhattan earns my dubious vote as the most highly regarded Allen film which I find least personally satisfying, though (naturally) there’s much about it to appreciate — and I’ll try it again in later years to see if my opinion has changed.

Having recently rewatched so many of Allen’s films during a short period of time, I’m once again enormously impressed by the trajectory of his creative vision — shifting from his “early, funny” films (each an enjoyably gonzo comedic treat), to the heartbreaking yet life-affirming insight of Annie Hall, to the devastating emotional rigor of Interiors, to the complexity and joy of Hannah and Her Sisters. Meanwhile, those interested in tracing thematic trends across an auteur’s lifelong vision will surely have a field day with Allen’s work, given how much of it is based so closely on elements of his own life — carefully crafted as fictional narrative, yet oh-so-clearly a manifestation of his own idiosyncrasies and interests. Some parallels are obvious — i.e., the close overlap between the three grown sisters in Interiors and those in Hannah and Her Sisters. Others are subtler — i.e., as Peary astutely points out in Cult Movies 3, the connection between Alvy Singer’s initially liberating yet ultimately claustrophobic “mentoring” of “naive” Annie Hall, and the “imposing, Nosferatu-like” role played by “Max von Sydow as Barbara Hershey’s possessive, soon-to-be-dumped mentor” in Hannah and Her Sisters.

Any discussion of Allen’s career would, of course, be incomplete without mentioning what he’s produced since 1987 — which amounts to an astonishing film-a-year, much of it (unfortunately) not worthy of a film fanatic’s attention. Below is a chronological list of his theatrically-released full-length features as of 2012:

- September (1987)

- Another Woman (1988) (not must see, but recommended)

- Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989) — MUST SEE

- Alice (1990) (not must see, but recommended for Allen fans)

- Shadows and Fog (1991)

- Husbands and Wives (1992) (not must see, but recommended)

- Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993) — MUST SEE

- Bullets Over Broadway (1994)

- Mighty Aphrodite (1995) (not must see, but recommended simply for Sorvino’s performance)

- Everyone Says I Love You (1996)

- Deconstructing Harry (1997) (not must see, but recommended once for diehard Allen fans)

- Celebrity (1998)

- Sweet and Lowdown (1999)

- Small Time Crooks (2000) — MUST SEE

- The Curse of the Jade Scorpion (2001) (not must see, but recommended for Allen fans)

- Hollywood Ending (2002)

- Anything Else (2003) (not must see; skip this one)

- Melinda and Melinda (2004)

- Match Point (2005)

- Scoop (2006) (not must see, but recommended)

- Cassandra’s Dream (2007) (not must see, but recommended)

- Vicky Cristina Barcelona (2008) (not must see)

- Whatever Works (2009) (not must see)

- You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger (2010) (not must see, but mildly recommended)

- Midnight in Paris (2011) (not must see, but recommended)

- To Rome with Love (2012)

It’s been too long since I’ve seen many of these films to say definitively whether I’d vote them as “modern must-see” titles or not — but the ratio of essential to non-essential titles in this list will certainly be much, much lower. I’ll check back in later, as I rewatch the second half of Allen’s oeuvre and carefully select the wheat from the chaff. [ADDENDUM: I’m casting my votes now, as I rewatch these later titles; as predicted, very few are “must see”, though a surprising number are recommended — at least for Allen fans.]

P.S. (8/9/12): I recently stumbled upon this indispensable website/blog for Allen fans:

http://www.everywoodyallenmovie.com/

It’s dedicated to much the same project I’ve been engaged in myself recently, albeit on a grander, much more detailed scale. You’ll find yourself unable to stop clicking from title to title, reading Trevor’s insights into each Allen film as he watches them in chronological order and makes extensive thematic connections. What’s most interesting to me is how strongly we differ in our critical opinions of many of Allen’s later titles, demonstrating once again how fickle and subjective Allen-allegiance can be; I think it ultimately comes down to each viewer needing to decide for him/herself whether any given (post-1987) title is worth watching or not. At any rate, definitely check his site out!

P.S.S. (1/8/21): Well, life keeps evolving, as does the internet. It appears that everywoodyallenfilm.com is no longer, and I can’t find traces of it anywhere — however, for diehard fans, there are other sites devoted to covering Allen’s oeuvre and ongoing projects, including https://www.woodyallen.com/ and http://www.woodyallenpages.com/. Allen has remained as prolific as ever, continuing to churn out roughly a movie a year since 2012 for a total of 7 additional feature-length films and a T.V. mini-series — none of which, sadly, I have any interest in checking out.