|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Lewis Milestone Films

- Soldiers

- Survival

- World War One

Response to Peary’s Review:

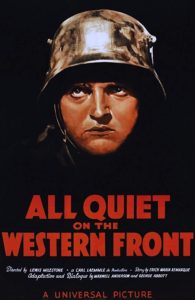

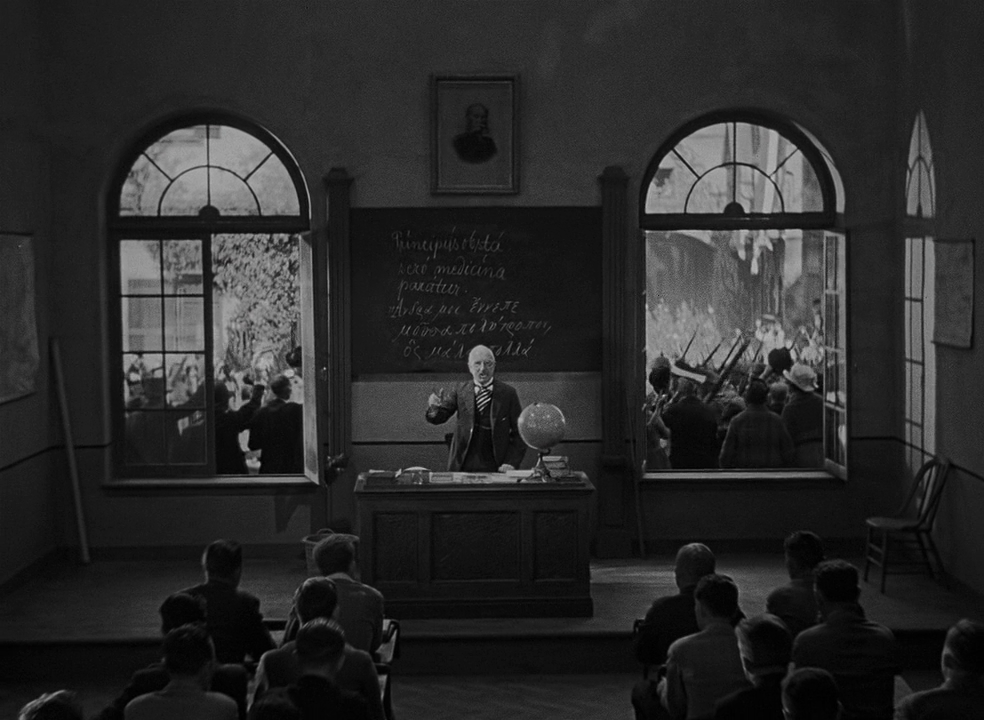

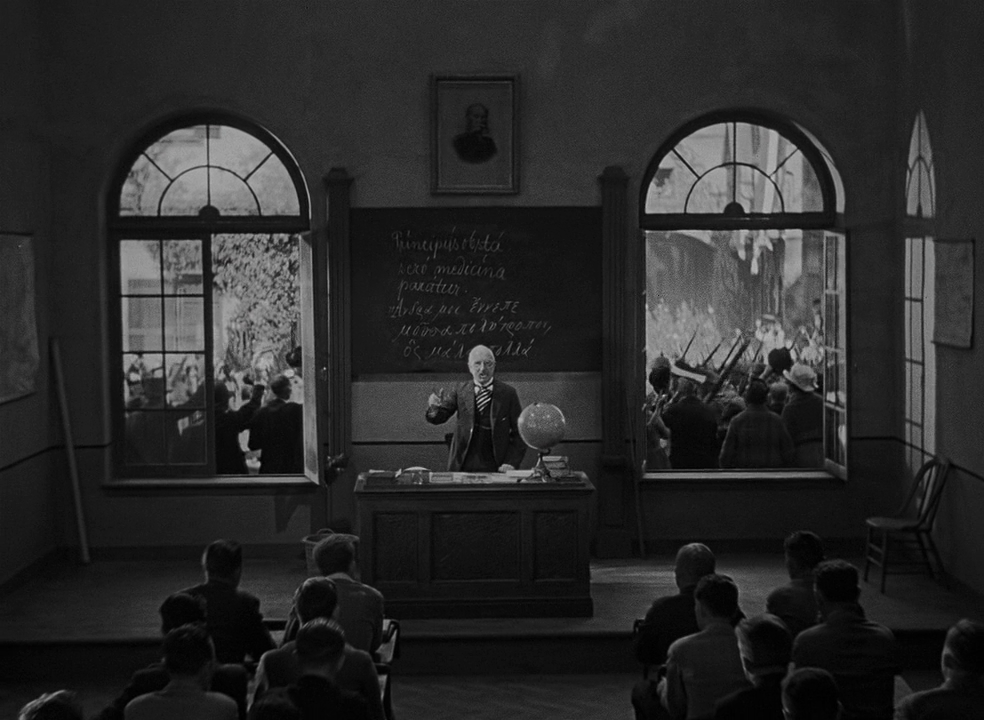

Peary writes that while “the most famous pacifist film is not as grisly as Erich Maria Remarque’s novel,” it “has enough horror and brutality to drive its anti-war theme home a hundred times over”. Influenced by a “rousing pro-militaristic speech by their professor”, a group of impossibly young and naive German teens quickly “discover that war has nothing to do with gallantry, duty, or the right cause” — instead, they “suffer through bombings, gassings, massacres, [and] hand-to-hand conflicts”. Peary argues that while “the dialogue scenes are static”, the “human story is powerful”, with “director Lewis Milestone’s visuals of the battle scenes… still impressive”, “effectively convey[ing] that being a soldier is a terrifying prospect.” Peary concludes his brief GFTFF review by noting “it’s unfortunate that films like this are never made when a war is in progress.”

In Alternate Oscars, Peary agrees with the Academy in naming this the Best Picture of the Year, and elaborates on what makes it so enduringly powerful. He writes that while “the boys enthusiastically enlist en masse, all hoping to be heroes”, “once in uniform, they realize that there is no glamour to war” — “instead, there are dictatorial officers, endless marchs, hunger, fatigue, nostalgia for home, rats in the trenches, mud and rain…” Indeed, there is “no heroism. Instead there is confusion, terror, hysteria, madness, amputations, [and] meaningless deaths. All that matters is survival, and those who survive are either insane, without limbs or sight, or unfit to return to civilization where old men still champion wars.” Most chilling and heart-stopping among many powerful moments is “the battle scene in which Arthur Edeson’s camera pans while charging soldiers are mowed down by machine-gun fire” — a scene “as impressive as it is terrifying”, and which “becomes even scarier when soldiers break through and jump into the trenches for hand-to-hand combat.” As Peary adds, “Significantly, not one shot is heroic or glamorizes war; instead we see how vulnerable all soldiers are and want to close our eyes until the fighting stops.” This almost unbearably impactful film will quickly convince you that war really is hell.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Powerful direction by Milestone

- Arthur Edesen’s cinematography

- Countless memorable moments

Must See?

Yes, as an enduring classic.

Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|