|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Flashback Films

- French Films

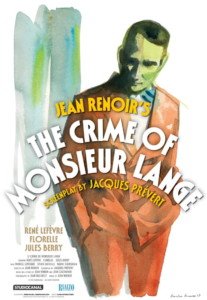

- Jean Renoir Films

- Revenge

- Womanizers

Response to Peary’s Review:

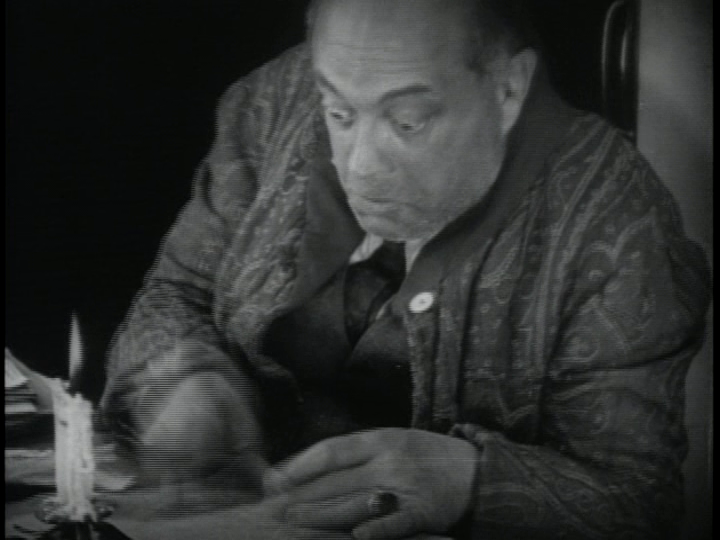

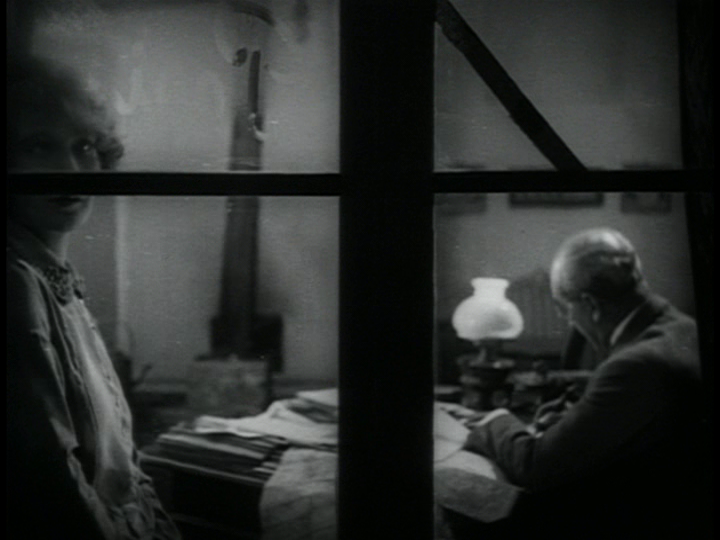

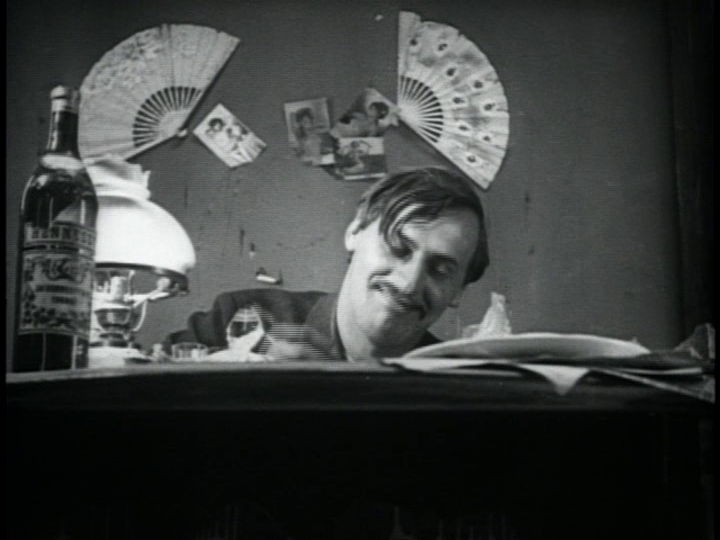

As Peary writes, “Jean Renoir’s first popular success has long been overlooked by those quick to champion Grand Illusion and The Rules of the Game” — however, he argues that “this is Renoir at his best,” providing “a marvelously moving, beautifully directed and acted celebration of romance, brotherhood, art, life, and the common French men and women who are guided by their hearts.” He writes that the title character, Monsieur Lange (Lefevre), “is a gentle, passive, low-paid worker in a publishing house run by the charming but ruthless Batala (Jules Berry)”:

… who has “sexually used” “every young female in this story” and “financially exploited” “every male”. He notes that “at first we are amused by how the fast-talking Batala charms everyone into doing his bidding (the scene in which he lavishes great praise on a creditor’s scruffy mutt is a classic)”:

Lange: “What a fine dog you have. I know a lot about dogs.”

Creditor: “Daisy’s a bitch.”

Lange: “Daisy? Ah, yes… an excellent breed.”

… but “by the time he seduces a vulnerable young laundress (and impregnates her”:

… “and gets Lange to sign away his rights to his Arizona Jim pulp western, we begin to realize that he is meant to personify evil (i.e., a fascist/money-hungry capitalist).”

Peary writes that this “picture has wit, warmth, [and] characters you care about” — and “what is most remarkable is the picture’s sexual maturity and frankness. This is no Hollywood film: we see Lange and his girlfriend in bed together”:

… “men take for granted that their lovers have had previous sexual experiences, a girlfriend’s pregnancy by another man is shrugged off, an unwed mother is accepted.” He concludes by noting that “this being Paris, both men… and women… are sexual prey: in Renoir, it’s important not to be isolated from those who care about you.”

I’ll admit to taking a moment to warm to the unusual pacing and narrative of this film, which moves quickly from character to character, showing us a mélange of individuals whose various roles in the story only gradually emerge as clear — but once we understand that Batala is, as Peary writes, the unambiguous villain of the piece (capitalist evil personified), we become more intrigued by how events will fall out — especially knowing from the outset (this is a flashback film with a give-away title) that Lange is being pursued for committing a crime, and that a priest Batala meets on the train will likely end up playing a role of some kind:

This fable about collective support in the face of oppression remains a powerful little tale, and is well worth viewing as an introduction to Renoir’s work.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Atmospheric cinematography

Must See?

Yes, as a fine early classic by Renoir.

Categories

- Genuine Classic

- Important Director

Links:

|