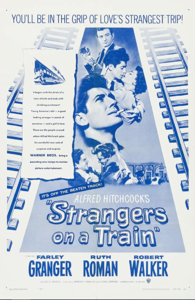

Strangers on a Train (1951)

“Everyone has somebody that they want to put out of the way.”

Synopsis: |

|

Genres:

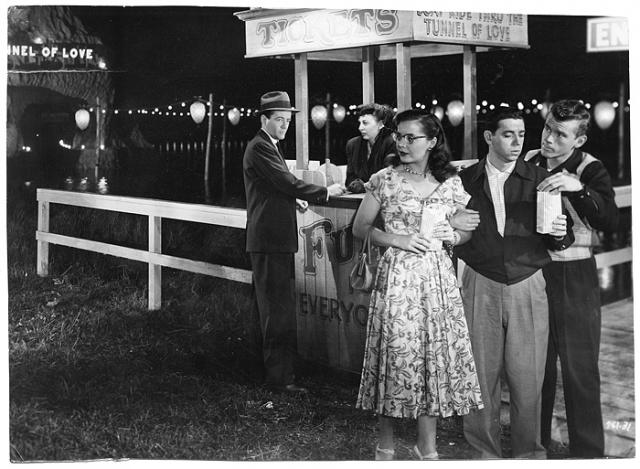

Response to Peary’s Review: With that said, the film has its flaws: as one avid poster on IMDb has pointed out, there are more than 20 instances in which the characters in the film act irrationally and/or foolishly, simply to move the plot forward (a policeman shoots into a crowd with children, for instance). But Hitchcock’s films aren’t designed to present the most “logical” progression of events; they’re strategically crafted for maximum dramatic and psychological effect. Indeed, the story is presented as a sort of “living nightmare” for Guy, who — desperately hoping for some kind of resolution to the seemingly impossible situation with his sluttish, obstinate wife (delightfully played by Elliott, a.k.a. Kasey Rogers, in Coke-bottle glasses) — finds that her convenient “disappearance” merely resolves one dilemma while opening up a host of others. Most of Peary’s review in GFTFF centers on an analysis of Walker’s character (Bruno Anthony), who he refers to as a “picaresque hero” — someone who, “if it weren’t for a domineering father and daffy mother (Marion Lorne), might have been a great person.” He argues that “we like this fellow Walker plays; it’s as if we were under his skin, sweating his sweat. We care more about his hurt feelings than about the survival of Guy and Ann’s relationship.” But I can’t entirely agree. While it’s true that Walker does a remarkable job humanizing Bruno, I disagree that we actually “like” him; he’s far too vengeful and unhinged to really empathize with. And while it’s true that Granger (who Peary argues is miscast; I think he’s ideal for the part) fails to project even a fraction of Walker’s complexity, his character remains at the very least a decent fellow, someone we can’t help hoping will emerge from the situation unscathed. Meanwhile, watch for a host of other engaging performances — most notably Patricia Hitchcock (in what was arguably the best role of her brief acting career) as Granger’s fiancee’s younger sister, and Marion Lorne as Bruno’s incomparably eccentric mother. Note: There are multiple other “layers” to the film as well; while Peary doesn’t touch upon it at all in his review, it’s impossible to ignore the homoerotic tensions between Walker (fairly openly “coded” as gay) and Granger (bisexual in real life). Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |

One thought on “Strangers on a Train (1951)”

A no-brainer must; one of Hitch’s richest films.

Here is a rare example of a movie that doesn’t botch the source material (Highsmith’s book, which I recently read) but, rather, re-invents it. The screenplay by Raymond Chandler (an inspired choice) seems to have taken the novel’s main premise (made clear when Guy and Bruno…what? ‘meet cute’?), the specifics of the first murder – and not much else; at least not in accordance with Highsmith’s structure or development. (A major departure has Guy as a tennis player in the film rather than an architect; certain other major elements – such as the deliciously wry Patricia Hitchcock character – are not found in the book at all.)

Yet, the overall result remains adequately faithful to Highsmith’s spirit even as it tones down the nihilistic pathology. Though the film is indeed very creepy, the novel is much more so.

I agree with the idea that logical analysis of the play-by-play action is of little importance here, and was apparently of little concern to both Hitch and Chandler. At any rate, scrutinizing the film in order to reveal it as a ‘house of cards’ just spoils the ‘fun’.

As well, I agree that we are not meant to empathize with Bruno (played to brilliant perfection by Walker, in the year that also saw his untimely death). We are, however, in a significant twist of the novel, clearly meant to be on Guy’s side since he is not depicted in the film as ‘the other side of the same coin’. Hitch seemed to prefer seeing his villains clearly drawn as villains first – and not necessarily people second – and he tended to be very watchful that the actors playing such roles refrained from too much, if any, humanization (as witness Joseph Cotton in ‘Shadow of a Doubt’, Tony Perkins in ‘Psycho’, etc.).

While it’s true that Highsmith was a lesbian (and that informed her work), the film of her book only contains – as I see it – a hint of the homoeroticism evident in what she originally wrote. So, while it’s certainly there in the movie, I only detect a slight suggestion of it (and, believe me, I was looking).

I do highly recommend the book, not only because it’s a gripping read (and you have to practically wring yourself out afterwards) but as a fascinating counter to the film adaptation.