Dead of Night (1945)

“There’s a ghost as well as a skeleton in everyone’s cupboard.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres:

Response to Peary’s Review: Most also agree that the fourth vignette (“Golfing Story”, directed by Charles Crichton) — about golfing buddies (Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne) whose rivalry for an indecisive woman (Peggy Bryan) leads to Wayne’s watery death and his resurrection as a vengeful ghost — seems out-of-place, given its decidedly lighthearted tone; Peary argues that it “should have been omitted” altogether, noting that “it was excised from the original print released in America”. Also missing from this original print was the third vignette (“Haunted Mirror”, directed by Robert Hamer), a creepy morsel about a man (Ralph Michael) who “looks into a newly purchased antique mirror and sees the room of the previous owner, a jealous maniac who strangled his wife”, then “becomes possessed” and “starts to strangle his own wife (Googie Withers)”; it’s a satisfying little thriller, though we can’t help wanting to know more about the characters and their back stories. The same holds true for the first and second vignettes (“Hearse Driver”, directed by Basil Dearden, and “Christmas Party”, helmed by Cavalcanti) — both of which, as Peary notes, “should have been expanded”. But it’s the connective story of this edited tale (directed by Dearden) which ultimately emerges as the unexpected shocker: what begins as a relatively straightforward tale of an everyman (Mervyn Johns) experiencing perpetual deja vu turns into a surprisingly complex meta-narrative. As noted by DVD Savant, “audiences even now will be thrown by the ending revelations, because few people expect Borges-like time-space enigmas to intercede in mundane filmic reality”. While the vignettes in Dead of Night aren’t quite as frightening or creepy as one might hope, it’s nonetheless satisfying to see the way this diverse team of writers, directors, and actors manage to pull their stories together into one cohesive nightmare. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories Links: |

One thought on “Dead of Night (1945)”

A once-must, for its place in cinema history.

Watching it again, the film now does come off to me as somewhat quaint. I’m told that this was Britain’s first real horror film. But, though a certain creepiness does remain, there’s more of a tentaive quality: the first two tales are shorter than they should be (for maximum effect), for example, and the golf sequence throws off the film’s overall tone.

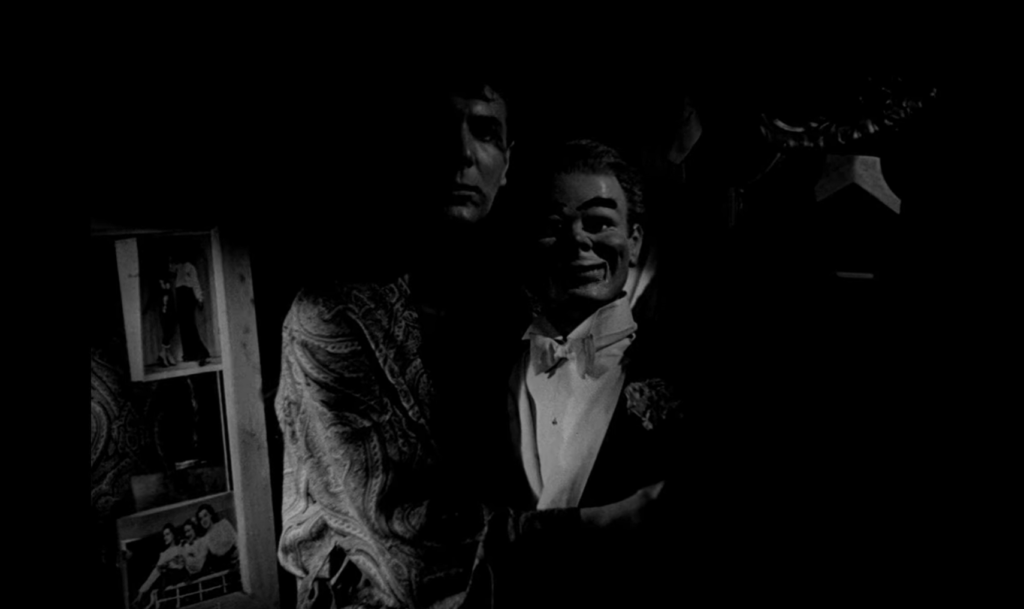

Still, there is the mirror sequence – with its appropriately strident score…and the dummy story (which, in 1964, would grow to full-length with ‘Devil Doll’)…and, best of all (to me), the whole frame of the film in general. I actually find it creepiest of all that, at the beginning of the film, the main character would be describing his worst feelings of impending doom to a group of strangers who are being almost nothing but nice to him (!). Of course, the visiting psychiatrist is a (necessary) cog in the wheel. But the protagonist is faced with a genuine fear that appears to grow as it continues being lost in a surrounding of perfect decorum.

(Truth be told, either that character has some very alarming and deep-rooted anxieties about life and death…or he should be careful about what he eats before going to bed. 😉 )