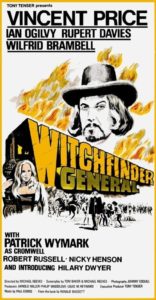

Conqueror Worm, The / Witchfinder General, The (1968)

“Men sometimes have strange motives for the things they do.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Response to Peary’s Review: Peary’s GFTFF review is lifted directly from his lengthier Cult Movies essay, where he contrasts this horror film (based in name only on a poem by Poe) with “all those enjoyable Poe films starring Vincent Price, like The House of Usher (1960), The Pit and the Pendulum (1961), and The Masque of the Red Death (1965)“, which were “intentionally claustrophobic, with almost everything taking place within secluded castles”, and evil — as “personified by the mad, hermitlike Vincent Price characters” — “confined to the castles themselves, so that if the castles are destroyed the evil within their walls will be destroyed as well.” In The Conqueror Worm, on the other hand, we “are presented with an evil that is overwhelming, invulnerable, and that will emerge victorious” — it is “not confined to a single castle but runs rampant across all of England, contaminating the people, wiping out whatever goodness exists and replacing it with a contagious sickness characterized by each ‘victim’s’ desperate need to be cruel to his fellow human beings.” Peary adds that two of Reeves’ greatest achievements with this film — his third and last after The She Beast (1961) and The Sorcerers (1967) — were managing “to keep Price from going into the ham actor routine that mars many of his performances”, and for keeping narrative tensions consistently high. He points out that the film starts with a “pre-credits sequence so powerful — a screaming woman being led to a scaffold where she is hanged — that the film must be kept at a high level of intensity in order to avoid a dramatic letdown”, but notes that Reeves is successful in maintaining “an extraordinary momentum throughout”. Viewers should be forewarned that “along the way there is much violence — executions, tortures, a nerve-wracking soldier-ambush sequence” — and “whenever there is a chance that the hectic pace might be slowing a bit, Reeves automatically has Marshall [Ogilvy] jump on his mighty steed and race it across the countryside”, thus never giving the audience “a chance to relax”. I agree with Peary’s closing statement that “by the end of the film it is as if you have just run the gauntlet”. With that said, this film’s relentless violence has a (sadly relevant) purpose, showing how easily mankind can descend into joy of torture — or at least mindless acceptance of it as commonplace and necessary. Reeves includes plenty of tracking shots showing villagers calmly watching as “witches” are burnt to death; minor facial expressions demonstrate that they likely believe the heretics deserve their fate. Also of note is the film’s gorgeous cinematography, showcasing real-life horror taking place in an atmospheric landscape of Gothic forests, meadows, village squares, and dank interiors. With his expert directorial hand, Reeves makes powerful visual statements throughout: for instance, as Ogilvy comes back to Dwyer and listens to her “confession” about what she’s done to try to save her uncle, she is framed by the word “WITCH” scrawled on the wall of a church behind her — but when Ogilvy brings her down to her knees with him to pray and ask God to marry them, the term neatly disappears from our view. In another notable instance, crashing waves at the seashore (freedom) turn into the fiery flames that will put an innocent victim to death. Reeves’ film is both brutal and brilliant, a worthy culmination to his far-too-short career. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories Links: |

2 thoughts on “Conqueror Worm, The / Witchfinder General, The (1968)”

A classic and very much a must see film for its historical relevance. It’s also a great horror film.

A no-brainer must-see, as a unique (practically one-of-a-kind) entry in the horror genre, and for Price’s performance and Reeves’ direction.

If I don’t watch this film once a year, it’s likely I see it every other year. It’s that good, that worthy of repeat viewings. Probably what I appreciate ‘The Witchfinder General’ (the better title) for most is the way it makes us re-think what a horror film can be.

As viewers, we can distance ourselves from many horror films because of the way the horror is often depicted: i.e., ‘real’ murders are often depicted unrealistically. (An exception being the shower scene in ‘Psycho’.)

But ‘TWF’ isn’t about the horror of murder – nor is it about anything that most horror films concern themselves with. It’s more about a philosophy – and how that combines with the thirst for power.

I don’t think Reeves was at all interested in shocking people for its own sake. I think his main intent was in realistically revealing – as closely as possible – the evil of the mind-set shown in the film… and the powerlessness that average people feel while in the midst of it. I also feel Reeves felt compelled to remind people that this was very much an abominably real – and shameful – chapter in history.

I’ve always liked the story told re: Price’s initial experience of working with Reeves: he didn’t like him, esp. when Reeves told him (in whatever words he chose) to not ham it up. As the story goes, Price reminded the relatively new director of the large number of films he’d appeared in and asked him, “How many films have *you* made?” Reeves’ response: “Two good ones.” …Price then did as he was asked. The upshot was that, when Price finally saw his total performance, he admitted that Reeves had been right all along.

I’m a huge Price fan – and though that means I’m a fan of a huge number of his performances, I would probably also say that his performance in ‘TWG’ is his best. It’s not just that it’s a committed performance; it almost borders on terrifying (in a way).

There will probably always be speculation re: how / why exactly Reeves died when he did. I don’t personally believe the talk of suicide; I think, at that point in his career, he had too much to say as an artist and was only beginning to come into his own as a visionary (and that he probably knew that). I tend to go with the theory that it was a fluke (involving a miscalculation with medications). We’ll never know for sure.

But, before he left us, he left us this remarkable film.