42nd Street (1933)

“Sawyer, you’re going out a youngster — but you’ve got to come back a star!”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

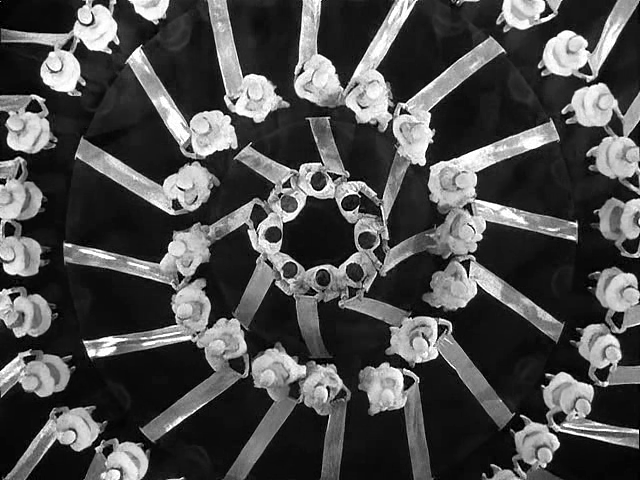

Response to Peary’s Review: Peary notes that the “picture ends with a bang”, with a production number (“42nd Street”) that — in typical Berkeley fashion — is clearly “too elaborate ever to be performed on a real stage, with sections filmed from above, women used as props to form geometric patterns, closeups, dollies, pans, and an ending in which Berkeley thrusts his camera forward between the spread legs of numerous chorines who stand on a revolving stage”. Before this extravaganza, however, we’re treated to several other enjoyable numbers (check out the surreal final moment of “You’re Getting to Be a Habit With Me”, performed by Bebe Daniels), as well as an enjoyably sassy Pre-Code script. (My favorite throwaway one-liner is Ginger Rogers’ snappy retort to a snarky competitor in line at a casting call: “It must have been tough on your mother, not having any children.”) Regarding the film’s reputation as campy, the primary element that causes one to guffaw these days is the notion that Keeler has any kind of viable or visible leading-lady potential; when Rogers gives away her own chance at fame, humbly allowing Keeler to take her place while citing Keeler’s superior dancing capacity, one literally gasps at the ludicrousness of her statement. Speaking of Keeler’s overall talents, this topic has been debated for years (a debate which continues on IMDb’s message boards). Peary — who writes bluntly in his Cult Movies essay that Keeler “taps like an elephant” — is not alone in his derision, but others come to her defense by noting that her unique tap style (known as “buck dancing”) was intentional, and deserving of the praise it received by critics at the time. My own two cents is that Keeler (or at least her character here) possesses nothing close to the requisite star-power needed to replace Daniels and wow the film’s fictional audiences — but she does adequately represent the fantastical notion that “any woman” might have a chance at fame, if only the stars align in just the right way; such was the power of escapist Depression-era cinema, of which this is likely the epitome. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |

One thought on “42nd Street (1933)”

A once-must for its place in cinema history.

~but it’s not really the iconic musical that many think it is. Prior to the film’s final 15 minutes (more about those presently), things do move along nicely enough thanks to Bacon’s direction and a somewhat snappy feeling to the script (especially with its punchy line every now and then, as noted).

But things don’t really take off until the last 15 minutes – during which we do (finally) get something to make us sit up and take real notice. The songs in the medley conclusion remain clever even today and they’re given signature Berkeley treatment (though, nice as it is, this isn’t Berkeley’s best work).

Note: Ken Russell borrowed significantly and delightfully from this film for one of his masterpieces, ‘The Boy Friend’.