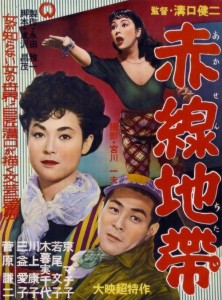

Street of Shame (1956)

“You can wipe off your rouge, but not the makeup of your trade.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Review: — it is nonetheless the only way they can earn enough money to pay off their debts, which range from a father’s bail bond, to medication for a TB-ridden husband, to a simple desire for fancy clothes and jewelry. There are many powerful moments in this at-times didactic, yet still consistently moving, film. My favorite has the mercenary Yasumi (Ayako Wakao) running into one of her regular Johns at a cafe while he is eating with his family, being introduced as his secretary, and giving him a sly wink when leaving. A particularly painful scene shows aging widow Yumeko (Aiki Mimasu) stopping to eat some noodles on her way to visiting her son, making herself presentable in the mirror, and being told snidely by the restaurant’s nursing proprietor, “You can wipe off your rouge, but not the makeup of your trade.” Perhaps the most startling scene shows tough, sexy young Mickey (Machiko Kyo) — who never stops eating, dancing, or shopping — propositioning her own father in angry defiance of his request that she come home and stop debasing their family name. While Mickey — a hip and sassy girl in her American pedal-pushers — appears to be eagerly embracing prostitution as a way of life, she, too, has skeletons in her closet which have led her down this tenuous, socially-caustic career path. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

Links: |

One thought on “Street of Shame (1956)”

Very much a must.

In a 33-year period, famed director Mizoguchi made 90 films – and still died rather young (58). ‘Street of Shame’ (the original title translates as ‘Red-Light District’) was his last, and among his best (possibly his most accessible).

As the madam of ‘Dreamland’ tells a police officer re: the proposed anti-prostitution bill, “Yoshiwara [the district] is 300 years old. Does an unnecessary business last so long?” From the standpoint of this all-around-sad affair of a film – with its semi-atonal, sci-fi score – members of Japan’s chapter of the oldest profession went from being often powerful (in their hierarchical struggle in days of old) to usually completely powerless as their open presence was dissolved. But, in many ways, the problems remained the same for work demanding a complicated web of association.

Though ‘SOS’ is well cast and all of the women (particularly) turn in strong performances, Kyo – from her first commanding entrance – clearly dominates and anchors the film. She operates from a simple platform – “Everyone’s selfish. …Deceive or be deceived.” – and, though not nearly as resourceful as Wakao’s character, does all she comes into contact with one better. Her character occasionally recedes from the proceedings but always returns with force – and is esp. (somewhat subtly) arresting in certain group scenes: watch her closely when a colleague is about to get married and then when the same colleague returns after her marriage crumbles. And, yes, the scene with her father is startling.

This is definitely not one to miss – and it has a memorable and melancholy coda.