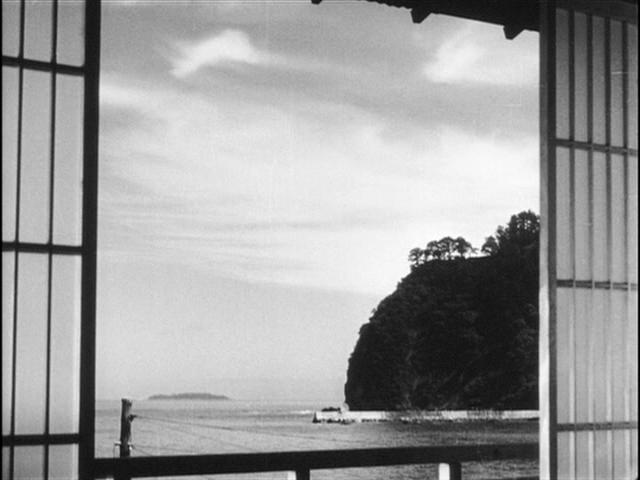

Tokyo Story (1953)

“We can’t expect too much from our children. Times have changed. We have to face it.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Response to Peary’s Review: Despite its prototypically Japanese setting, the themes in Tokyo Story are highly universal, and those who have seen Leo McCarey’s Make Way for Tomorrow (1937) will recognize many parallels. Just as the elderly couple in that film (Victor Moore and Beulah Bondi) are viewed as a burden by their married children, Ozu pulls no punches in portraying the impatience Ryu and Higashiyama’s children feel about their parents’ temporary presence. The couple’s beautician daughter (played with wonderfully snippy self-righteousness by Haruko Sugimura) comes across as especially shallow and uncaring, but she is not alone in her desire to be able to resume the rhythms of her regular life once her parents are gone; indeed, the son (Shiro Osaka) living closest to Ryu and Higashiyama in Onomichi has even less interest in caring for them, and must be reminded by his co-worker about the importance of filial concern. Interestingly, it is Ryu and Higashiyama’s non-blood-relative — their daughter-in-law, Noriko (Hara) — who becomes the most sympathetic character in the film. This lovely young widow is genuinely pleased to spend time with the parents of her husband, who died eight years earlier in the war; as Peary points out, the scene where she sees Ryu and Higashiyama looking at a photo of their dead son and “quickly runs to a neighbor to borrow fine cups for the occasion” is truly touching. Only someone like Noriko — who has already experienced the loss of a loved one early in life — can understand “the transiency of life, [and] the need to care about people when they are still alive.” Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |

One thought on “Tokyo Story (1953)”

A must – and, though I’ve never thought of an Ozu favorite, this is probably it. Odd that my favorite of his is the one that is, as you say, “perhaps his most beloved in America” as well as internationally, and that my next favorite, ‘Tokyo Twilight’ was perhaps Ozu’s biggest commercial failure in Japan and is still not really available in the US. I would venture to say that, because of its universality, if you are going to see only one Japanese film that is not anime or about samurai warriors, this is the one to see. The overall mood of ‘TS’ is somewhat elegiac and shares what would later be writer Yukio Mishima’s sentiment: Japan modernized at the expense of its soul. In that sense, the eventual death of the mother can be seen as symbolic. As you also more or less state, the film’s simple title suggests that it is more about Tokyo than its characters (the name ‘Tokyo’ is used constantly in the script). The sense of depersonalization is clear – even the nearby hot spring resort Atami appears less than restful, and the emotional distance of the children is chillingly revealed when, out of embarrassment, the most insensitive of them refers to her parents (within earshot) as “some friends from the country”. Ozu’s style is so mild throughout, however, that the sadness of the film’s journey is softened, and would remain so if Hara’s cryptic statement to her sister-in-law – “Life is nothing but unpleasant things.” – was not trumped by what she tells her father-in-law: “I’m not that nice woman [that you think I am].” Superbly shot in a minimalist way, this is a very powerful film experience. Having lived in Japan for over a decade, I have a special fondness for it – it’s particularly nice to see the various small touches not evident to the average Western viewer: for example, Sugimura’s beauty salon is called ‘Urara’ – an approximation of the American expression “Oo-la-la!”