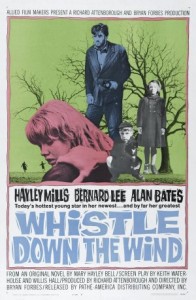

Whistle Down the Wind (1961)

“[It’s] Jesus — He’s in our barn. He’s come back.”

|

Synopsis: |

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Review: This powerful opening sequence — quiet and grim, yet hopeful at the same time — effectively establishes a tense dialectic between childhood idealism and adult pragmatism, a theme which continues through the entire film. The notion of these village children mistaking a scruffy, bearded stranger for Christ is highly credible, as is their quest to keep him safe from the evil hands of Adults Who Want Him Gone — after all, if adults will kill innocent kittens, what aren’t they capable of? Fortunately, though grown-ups may be the ones in power most of the time, children easily trump them in terms of their cleverness, imagination, and sheer trust in goodness, as this film ably shows. In addition to its provocative, unusual storyline, Whistle Down the Wind benefits from marvelous acting. Mills is once again natural and vibrant in a role which required her to ditch her perfect Queen’s English for a Northern dialect, and Alan Bates (in his film debut) wisely plays The Man (a.k.a. “Jesus”) as someone reticent and careful rather than vicious and bold, thus allowing the children’s impressions of him to form the bulk of his characterization. The cast of local children (labeled “The Disciples” in the film’s closing credits) are appropriately diverse in both appearance and demeanor, and the town’s adults (including Diane Clare as the children’s well-meaning Sunday School teacher, Bernard Lee as the siblings’ harried yet concerned single father, and Hamilton Dyce as the local vicar) are realistic as well. But the film’s stand-out performance undeniably belongs to the youngest Bostock sibling (Charles), played by Alan Barnes — who, as Bosley Crowther of the New York Times put it, “is absolutely the most terrific little fellow we’ve ever seen in a film.” Charles is the type of precocious kid who suddenly announces out loud at the breakfast table: “198”, then explains — as though the relevance and importance of this numerical fact should be obvious — that this is how many eggs he’s eaten since Easter. Charles is a boy who requires concrete proof of anything in order to be persuaded, and when “Jesus” allows the kitten Charles has placed in his care to die, Charles’s faith is suddenly and irreparably damaged: “It isn’t Jesus. It’s just a fella,” he takes to announcing with cynical disdain. Ultimately, however, Whistle Down the Wind is most concerned with Mills’s character (Kathy), and how she negotiates the tricky terrain of childhood conviction in the face of adult authority. Fortunately, the film builds to a credible denouement, with the movie’s final scene arriving as a satisfying solution to what seemed (to me at least) like an impossible task — bringing about justice for the fugitive’s crimes without shattering Mills’s faith completely. It is a testament to this fine, original film that it manages to achieve both. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

Links: |

2 thoughts on “Whistle Down the Wind (1961)”

Yes, very much a must. It’s puzzling, to say the least, that this film is so difficult to find. I’ve always thought it would be a good one for tv at Christmastime (are you reading, Robert Osborne?) but I’ve never seen that happen. The story (written by Hayley’s mom) struck me as possibly a response in part to odd behavior in the name of Christianity. In short, it’s not surprising that Kathy (Hayley) doesn’t believe in Jesus at the top of the story, since (as we see throughout the film) supposed believers around her lean toward the unenlightened (shall we say) or ineffectual (even if nice). But, when faced with a ‘second coming’, it’s fascinating watching Kathy’s devotion develop. Perhaps my favorite scene occurs in the schoolyard: a bully has been tormenting children who say they’ve seen Jesus, and Kathy stands up to him. It’s a stunning moment. The film, as you say, is finely crafted in all aspects – and at times even quite funny. It is a rare and marvelous movie about faith and should appeal to anyone who, like myself, quite often finds faith at very obvious odds with organized religion.

Ah, yes, this *would* be an excellent choice as a Christmas-time airing — especially given the unique melodic use of “We Three Kings of Orient Are” as part of the film’s soundtrack…

My rather obvious take on the film’s theme of Christianity is that the children (rather than the supposedly pious adults around them — i.e., the vicar) are shown to be the ones exhibiting “true” faith and Christian charity in their behavior; on the other hand, since Bates is clearly (?) NOT Jesus Christ returned to Earth, the film makes the excellent point that the logistics of Jesus’s return aren’t what matters — it’s how we react to such a concept, and how we treat others in the meantime, that counts.