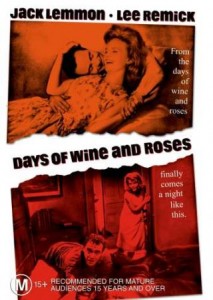

Days of Wine and Roses (1962)

“You and I were a couple of drunks on the sea of booze, and the boat sank.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Review: Indeed, it’s Lemmon’s performance here which ultimately kept me vitally engaged in the story. While his character starts off like simply a variation on the fun-loving jokesters he so often portrayed, Lemmon quickly invests his “Joe Clay” with far more depth and pathos than one might expect. We fully sympathize with the frustrations he feels in his job, and understand how the social drinking he’s expected to engage in likely accelerated his addictive approach to alcohol. When he’s first introduced on-screen, he’s already so immersed in destructive drinking patterns (without realizing it) that we can’t help wondering why Remick doesn’t react with a bit more concern — except for the fact that she appears to love him unconditionally. Indeed, it’s to Miller’s credit that so much care is taken to fully establish Lemmon and Remick’s characters as romantic individuals who fall deeply in love with one another before communal drinking enters the scene; they are clearly soulmates, which helps to ground the film as a tragic love story, first and foremost. Lemmon’s inevitable next step is turning his beloved teetotalling wife on to boozing, in a much more disturbingly manipulative way than happens, for instance, between Al Pacino and Kitty Winn’s characters in 1971’s The Panic in Needle Park (wherein Winn is curious enough to try heroin herself, but is never pushed). Miller’s point, we learn, is that alcoholics will always try to push or guilt the ones they love into joining them — and that’s what perhaps remains most unique about this cinematic presentation of alcoholism: the way we witness its effects on a mutually drinking couple, not just an individual. To that end, Remick’s descent into alcoholism comes across as less authentic than Lemmon’s, perhaps due to the stage-bound nature of the screenplay, which skips across enormous periods of time. We see Remick tentatively joining her husband in a hard drink for the first time, and then suddenly alcohol has become so second-nature in their household that it’s causing irreparable damage. From what I’ve heard (and seen, in brief snippets), Piper Laurie — star of the original teleplay — was a bit more effective at portraying this undeniably complex character (though Remick remains sympathetic throughout, and certainly gives an impassioned performance). Speaking of the teleplay, kudos must be given for the decision to retain the story’s original bleak yet realistic ending. It’s a respectful finale to the hard-hitting ride we’ve engaged in, and one appreciates the honesty it offers in its assessment of the chances for recovery. To that end, along with I’ll Cry Tomorrow (1955), it provides one of the earliest on-screen depictions of Alcoholics Anonymous as a viable option for alcoholics with nowhere left to turn (and Jack Klugman turns in a fine, subtle, believable performance as Lemmon’s AA mentor, patiently counseling him through the worst of his challenging decisions). It’s refreshing to finally hear alcoholism acknowledged as the mysterious addiction it is; what a positive shift from the days when alcoholic characters such as Ray Milland’s Don Birnam in The Lost Weekend (1945), or Susan Hayward’s Angie Conway in Smash-Up: The Story of a Woman (1947), were — out of sheer ignorance — implicitly condemned for their behavior. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

Links: |