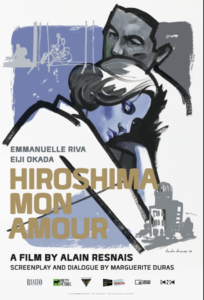

Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959)

“Why deny the obvious necessity of remembering?”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Response to Peary’s Review: … and “parallel montage whereby juxtaposed shots of [Riva’s hometown of] Nevers] and Hiroshima are filmed similarly and at the same speed — so that the unity of past and present (an important theme) is conveyed.” Also unique to this groundbreaking film are “surreal tracking shots of empty Hiroshima”: … and “the insertion of footage from the Japanese film Hiroshima [1953], with its grisly shots of A-bomb victims.” However, Peary posits — though I and many others disagree — that “while the film’s technical achievements are vast, there are problems with the central storyline.” He argues that despite “Resnais and Duras den[ying] that they were trying to draw parallels between the Hiroshima holocaust and the tragedy that befell Riva in Nevers at the same time,” they nonetheless “offer as a theme that love will vanquish terrible memories,” “suggesting that the memory of Nevers is as tragic to Riva as the memory of Hiroshima is to Okada but presuming that the Japanese are trying to forget about Hiroshima in order to move forward.” Frankly, I don’t see any of these ideas playing out in the film. Love is not presented as a way to eradicate terrible memories; rather, sensual connection is shown as a form of visceral engagement with uncomfortable truths. By pointing out parallels between the bombing of Hiroshima and Riva’s past — when the German soldier she was in love with “was killed by a sniper on Liberation Day” and “she had her hair shorn by villagers, and her parents locked her in a cellar,” and “at one point she had a mental breakdown”: — Resnais and Duras are simply making note of the many (indeed, uncountable) tragedies that befall people across the globe as they go about their daily lives during wartime. Peary seems to be part of a critical camp asserting that “a major problem” with this film “is that Duras did not know what to do with Okada, or know what he represents,” so “Duras concentrates on Riva and foolishly, and insultingly, ignores Okada’s story.” Peary adds: “That Riva tells [Okada] her past and doesn’t ask him to reciprocate and that he accepts this suggests that Duras regarded the white woman as being more important to the film than her Japanese lover.” However, we now understand that attempting to represent someone else’s lived experience in art — while occasionally successful — is generally not recommended; rather, one should write about or from one’s own truths, which is exactly what Duras does here, to strong effect. Since the publication of Peary’s GFTFF in 1986 and 1987, we (film fanatics) have many more resources available to help us understand and contextualize the titles he’s listed and reviewed — including restorative DVDs with commentaries and online analyses and discussions (i.e., through blogs and videos posted on YouTube). This film is, to me, an example of where Peary’s reviews begin to show their age: he was writing at a time when nuclear threat (though still very present and real) was at the forefront of everyone’s minds, and I believe he writes about this film through that Cold War-era lens of (justifiable) paranoia. What our country did to Hiroshima remains undeniably controversial (to say the very least), and of course a false equivalency should never be made comparing this catastrophic event to one young woman’s shaming at the hands of fellow villagers. But what Resnais seems to be saying here (though he has professed he doesn’t analyze his own films — he simply makes them) is that grief and unspeakable trauma at all levels resonate across geographic, gender-based, and cultural boundaries; only by deeply listening to one another can we begin to process the harm we cause each other — and yes, Okada’s character should be given a chance to make a film from his own unique perspective (it’s a movie I’m sure we’d all be eager to watch). Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |

One thought on “Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959)”

A once-must, as a uniquely challenging film experience.

This is only the second time I have seen this film. The first was many years ago in NYC; my best guess is that I saw it at the Bleecker Street Cinema on a double-bill with ‘Last Year at Marienbad’. Seeing it again did not particularly alter its initial impact; I felt just about the same reaction as I did then. ~ which leads me to think that this may not be a film that benefits much from repeat viewings. What it has to say it says rather loud and (more or less) clear the first time.

~ though, simultaneously what it ‘means’ in detail could easily be up to the individual depending on the extent to which it touches individual lives. (I can’t say I related to it, necessarily, but I can empathize.)

I would agree that “Resnais and Duras are simply making note of the many (indeed, uncountable) tragedies that befall people across the globe as they go about their daily lives during wartime.” That seems to sum up the film rather well.

[There have, of course, been many films about the German occupation in France – but cinema history has rarely explored the bombing of Hiroshima (and Nagasaki). Along those lines, and from the Japanese POV, a particularly potent entry is Shohei Imamura’s ‘Black Rain’ (1989).]