|

Synopsis:

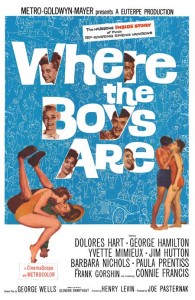

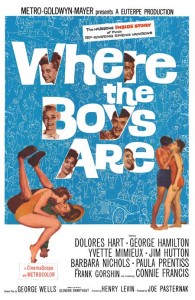

A group of midwestern college girls (Dolores Hart, Paula Prentiss, Yvette Mimieux, and Connie Francis) head to Fort Lauderdale for spring break, seeking romantic happiness and adventure in the sun — but they quickly find that dating is much more complicated than they anticipated, as Mimieux becomes sexually involved with a series of partying “Yalies”, Prentiss struggles to maintain her “good girl” status while dating an eccentric student (Jim Hutton), Hart dates a suave millionaire (George Hamilton), and Francis desperately pursues a quirky jazz musician (Frank Gorshin).

|

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Coming-of-Age

- George Hamilton Films

- Jim Hutton Films

- Paula Prentiss Films

- Sexuality

- Yvette Mimieux Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

Peary argues that while this “cult favorite” (directed by Henry Levin) is “dated in many ways”, it remains an “enjoyable, offbeat, interesting film with appealing performances by the lead actresses”. He points out that “it’s surprisingly more advanced than other films of the period in regard to sex”, noting that “the dialogue about sex is frank” and that “it’s clear that our four girls are in search of boys for sex” (a point I can’t quite agree with, as discussed below). He further notes that “the four leads are very appealing”, given that they “all have a sense of humor” and “their characters are believable”; he commends the script for providing us with an “early film in which the girls are supportive friends, rather than rivals”. In his Cult Movies 3 book, Peary provides a much more detailed analysis of the film, describing its many differences from the novel it was based on (by Glendon Swarthout), which is apparently even more sexually explicit, and focuses primarily on the sexual adventures of Merritt (Hart).

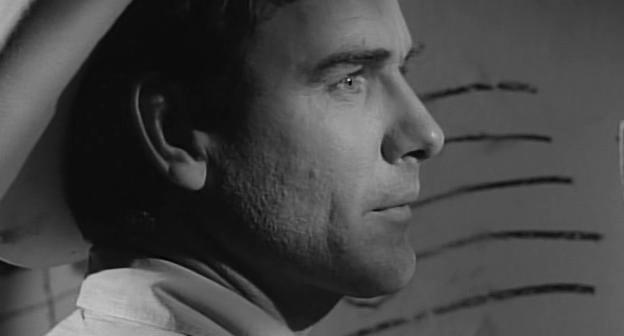

In Cult Movies 3, Peary concedes that WTBA shouldn’t really “be taken all that seriously”, given that “any picture about the students who migrate to Spring Break in Fort Lauderdale is bound to be somewhat stupid and junky”. He further points out that one shouldn’t forget “this picture actually has George ‘Mr. Tan’ Hamilton striding across the beach — an image that never fails to delight camp-movie addicts”. However, he argues that the film “is above being enjoyed only on a camp level”, given that “there is much to appreciate” — including “young heroes and heroines” who are portrayed as “caring, smart, and, ultimately, responsible”, and men who “show… respect for the women they’re attracted to”. The exception to this latter statement is, of course, the tragic subplot involving Mimieux’s fatally naive sexual interactions with a group of faux-Yalies — but it’s to the film’s credit that these male characters never emerge as anything other than bit players designed to play slimy louses.

As noted above, I don’t quite agree with Peary that all the girls in this film are interested in pursuing sex per se. While they are all sexually curious to one extent or another (who isn’t?), it’s evident that they’re primarily looking for boys to date, to have fun with, and to possibly turn into longer-term mates. Prentiss’s “Tuggle”, for instance, is a self-avowed “good girl” who makes it clear that she’s exclusively interested in finding a man to settle down with: “Girls like me weren’t built to be educated. We were made to have children. That’s my ambition: to be a walking, talking baby factory.” In her screen debut, Prentiss has an appealing comedic presence, and her interactions with lanky Hutton generally ring true. Much less satisfying is the character played by Connie Francis, who nicely sings the title song but otherwise is relegated to a thankless role as the girl desperate to catch a man, any man; she’s too attractive to merit this type of degrading characterization, and I don’t blame her for dismissing the film later in her life as terrible.

Note: Where the Boys Are remains of minor historical interest as well simply given that its lead, Dolores Hart, left Hollywood after making this film to become a lifelong Benedictine nun in Connecticut.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Yvette Mimieux as Melanie

- Paula Prentiss as Tuggle

- Dolores Hart as Merritt

Must See?

Yes, once, simply for its (relatively) bold exploration of ’50s sexual mores. But I doubt it holds much of its cult status any longer.

Categories

Links:

|