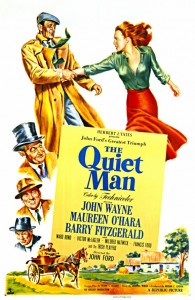

Quiet Man, The (1952)

“I’m Sean Thornton and I was born in that little cottage. I’m home, and home I’m going to stay.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Response to Peary’s Review: In his GFTFF, Peary analyzes the film’s sexual politics, noting that Mary Kate’s refusal to “consummate [her] marriage if she doesn’t have the dowry” makes her like a “modern woman”, given that she “doesn’t want to enter a relationship unless it’s on equal terms”. He writes how refreshing it is that, despite their obvious challenges, Mary Kate and Sean ultimately both view each other with maturity, love, and respect. Mary Kate “decides to have sex with Sean although he has not come through for her”, given that she “senses that he has reasons for not challenging her brother, although she herself may not understand them”. Similarly, Sean “challenges Will for Mary Kate’s sake”, conceding “that her reasons for wanting the dowry are not trivial, although he doesn’t understand them”. Peary goes on to note that “there’s so much Irish humor in this film and so many quirky characters that one tends to overlook that just below the surface there is much seriousness, hurt, and guilt; both Sean and Mary Kate are tormented in real ways and we feel for them”. Finally, Peary points out that while “Ford was never known for ‘love scenes’… the silent passage in which Sean and O’Hara hold hands, race for shelter from the sudden rain, and then stop, clutch (he drapes his sweater over her), and kiss as the rain soaks through their clothing is incredibly sexy”; I agree. Wayne and O’Hara are both in top form here, and are indeed — as Peary notes — “one of the screen’s most romantic couples”. In Alternate Oscars, Peary names Wayne Best Actor of the Year for The Quiet Man, and provides a detailed analysis of why this performance was one of Wayne’s best and “most relaxed”. He notes that Sean “is Wayne’s gentlest character”, that he’s “formidable” but without McLaglen’s “need to be a bully or braggart”. As Peary writes, “He has such confidence in his masculinity that he is polite, emotional, sentimental, and sweet enough to plant roses”, never “hid[ing] his love from Mary Kate, [and] never assum[ing] a paternal or authoritarian stance with her”. Indeed, it’s easy to see why O’Hara would fall in love with him — though naturally, she’s equally appealing, for her own reasons. This romantic couple is one we truly enjoy watching on screen. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |