|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Historical Drama

- Military

- Russian Films

- Sergei Eisenstein Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

Peary argues that this “monumental achievement by Sergei Eisenstein” is “his greatest film” — a “visual tour-de-force about Russia’s heroic 13th-century prince [who] forms a great army to wage war against the seemingly invincible Germans who have invaded the country.” He refers to it as “a peerless propaganda piece that extols Russian nationalism, displays the courage of the common Russian in battle, and viciously attacks Germany, Russian’s historical enemy, which in the 1930s was again on an imperialist march in which impersonal medieval-like soldiers committed atrocities in the name of Christianity.”

He adds that just “in the same way that Triumph of the Will is fascinating when Hitler mingles with his adoring subjects,” it’s fascinating “how Eisenstein humanizes his hero… to show he is not superior to the Russian soldier or peasant, just a better leader.”

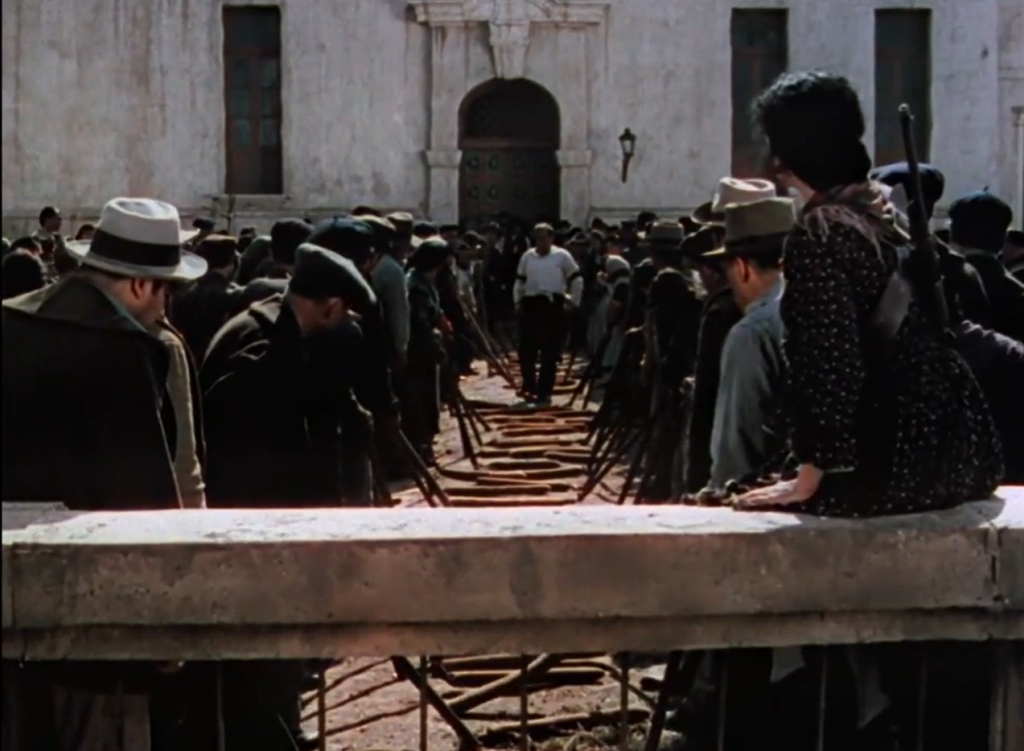

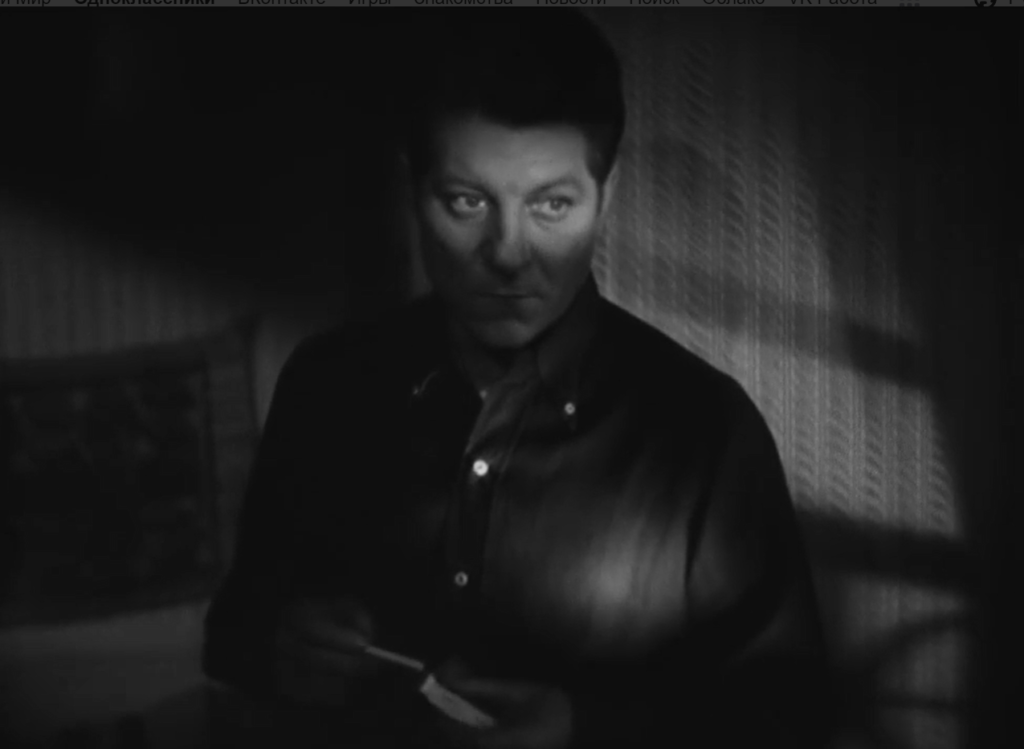

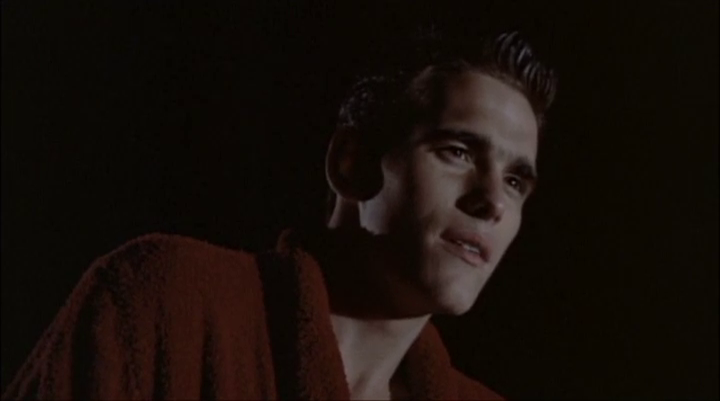

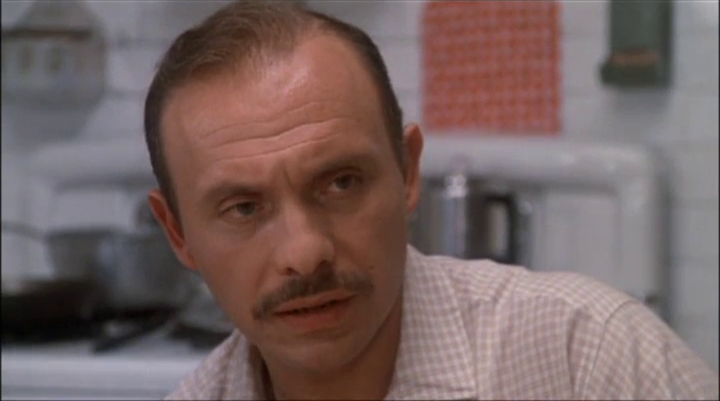

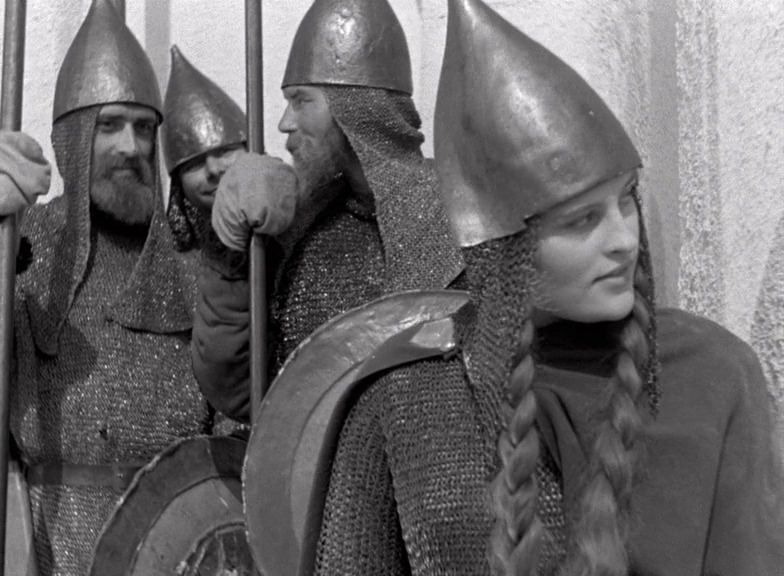

For example, “he never talks down to his men; he lets the people decide what to do with his prisoners;” etc. Peary writes that “common men are elevated to Alexander’s level,” given that “Eisenstein films them with a camera tilted upward and sets them in the foreground against the gray sky (there is always space behind them) so that they look enormous, like heroic epic figures of Alexander’s magnitude.”

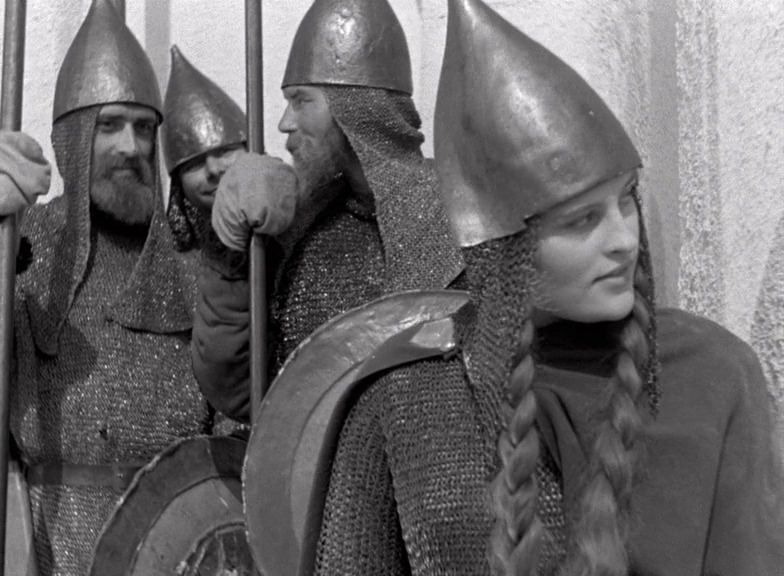

He points out how important it is that “we see the soldiers” in battle, not Alexander, and mentions “a subplot in which each of two friendly soldiers [Vasili Buslai and Gavrilo Oleksich] hopes to win the hand of a young woman [Valentina Ivashova] by fighting more gallantly than the other,” which comes across “like a stock Hollywood storyline.”

Peary inaccurately adds, “Only in this case the woman is also a warrior, fighting alongside the men”; this is actually a different female protagonist (Aleksandra Danilova) who nonetheless plays an important and distinctive role later on:

Peary notes that “Eisenstein’s picture is known for its remarkable close-ups”:

… its “innovative use of the frame (whereby action is taking place in several different planes and as far back as the eye can see)”:

… the “beautiful shots of man and landscape”:

… a “mix of realism and theatricality, gorgeous pageantry”:

… “and Sergei Prokofiev’s grand score.”

He asserts that “the climactic Battle on the Ice, a lengthy [37-minute], precisely directed sequence that employs thousands of warriors and horses, is perhaps the greatest battle scene in movie history” (at least up to that time), and “can’t be described properly without actually seeing it”:

He adds that he suspects “Eisenstein received special pleasure from directing the segment in which the ice breaks and hundreds of Germans drown,” given that we “are seeing Russia itself literally swallow invaders.”

Peary concludes his review by writing, “I admit some Russian classics are boring, but not this masterpiece.” While I agree this film is masterfully made on every level — especially given the severe Stalinist constraints Eisenstein was working under — it’s not a film I personally would return to numerous times, other than to analyze it from a stylistic perspective. I’m most taken with the striking costumes and sets, which effectively hearken back to a distant time and place. With that said, it’s most definitely worth a one-time look by all film fanatics.

Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

- Fine sets, costumes, direction, and editing

- Sergei Prokofiev’s score

Must See?

Yes, simply for its historical significance within Russian cinema.

Categories

- Historically Relevant

- Important Director

Links:

|