Mean Streets (1973)

“Honorable men go with honorable men.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

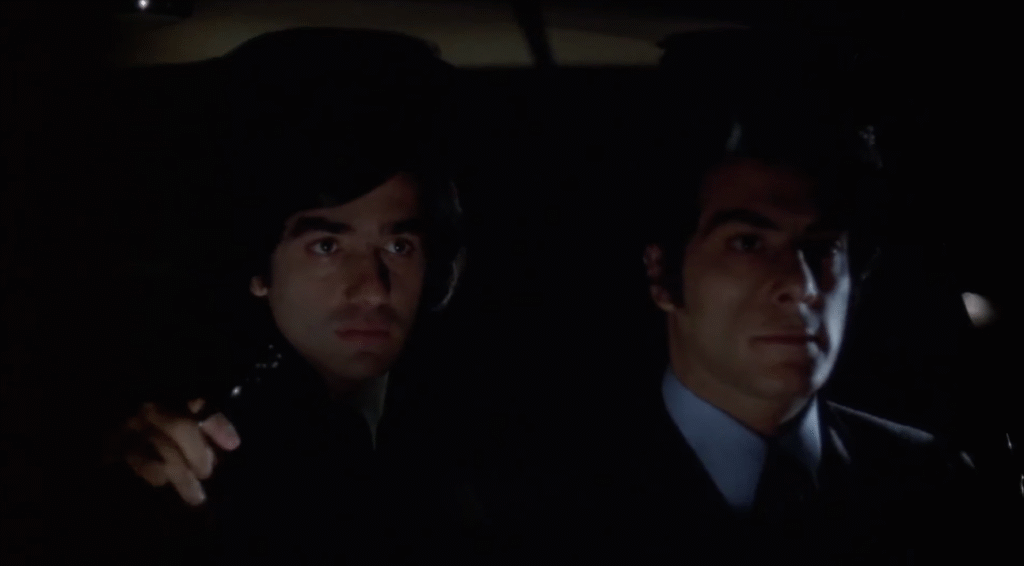

Response to Peary’s Review: Specifically, the storyline centers on Harvey Keitel’s Charlie, who “wants his Mafia uncle [Cesare Danova] to give him a restaurant that was taken from its rightful owner” — but in order to achieve this goal “must keep secret his friendship with stupid, irresponsible, reckless Robert De Niro (who became a star as Johnny Boy)”: … and his “love for De Niro’s epileptic cousin, Amy Robinson.” The bulk of Charlie’s time is spent “getting De Niro out of trouble… and eventually tr[ying] to get him out of town to avoid a loan shark (Richard Romanus) … to whom he’s deeply in debt.” Peary describes this film as “an alternative to Diner,” showing “young Italian buddies hanging out” in a bar, “carrying on conversations (heavily improvised) that have more slaps and shoves than words, holding two-minute grudges against each other, losing their tempers”: … “discussing what’s happening on the streets, making a play for women, scheming to get cash to see a movie up on 42nd Street, figuring out how to smooth things over between De Niro and Romanus, [and] watching strangers engage in violence.” Peary notes that while “Scorsese calls attention to his characters’ foul racism and [their] foolish male posturing” he “sees these young men sympathetically, as victims of their crowded, brutal, corrupt hell-town.” He points out that the “film has [a] distinct rhythm created by [a] rock-band score, camera movement, [and a] special brand of patter between characters”; meanwhile, “the strong use of city locales indicates Scorsese was an expert on post-WWII Italian neo-realist films.” Ultimately, he argues that “this remains one of Scorsese’s most exciting efforts.” While I appreciate all of Peary’s points — and can see how Scorsese fans would view this film as a powerful harbinger of what was to come — I differ from most critics in that I don’t see it as necessary viewing in its own right. There is little satisfaction in watching these young men hanging out and wreaking havoc; while Scorsese’s camerawork is consistently creative and Kent Wakeford’s cinematography is highly atmospheric, the storyline they’re working in service of doesn’t quite pay off. Watch for David Carradine as a drunk in the bar who meets a violent (what else?) end: … and Scorsese himself in a small but crucial (and violent; what else?) cameo near the end. Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments: Must See? (Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |

One thought on “Mean Streets (1973)”

(Rewatch 7/1/22, first viewing since its release.) A once-must, as a signature (and influential) film by a major contemporary director.

Overall, Scorsese’s films that focus on violence have limited appeal for me personally. One reason I never returned to this film until now is because of the number of ways that I find it unappetizing.

Still, as he made clear, he made a film about his own experiences. The film “was based on events Scorsese saw almost regularly while growing up in New York City’s Little Italy.” (Wikipedia). I rarely cite a critic’s take on a film. However, in Vincent Canby’s view, “no matter how bleak the milieu, no matter how heartbreaking the narrative, some films are so thoroughly, beautifully realized they have a kind of tonic effect that has no relation to the subject matter.” (Wikipedia)

While watching, it’s not all that necessary to follow the film’s subject matter – one way or the other, its essence comes through, as well as the singularity of Scorsese’s viewpoint.

I prefer this film over Scorsese’s much more brutal and lurid ‘Taxi Driver’ (which I have a hard time even thinking about revisiting anymore). Its importance in ’70s cinema seems undeniable.