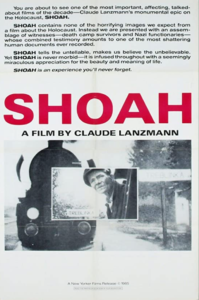

Shoah (1985)

“It’s hard to recognize, but it was here.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Response to Peary’s Review: Lanzmann interviews many different impacted individuals, including “concentration camp survivors (their stories are horrific) who often did special work duties that kept them alive (one cut hair of women going to the gas chamber, another cleaned the crematorium, etc.).” They tend to “talk without emotion, then something snaps and they burst into tears, and Lanzmann [controversially] urges them to continue.” Indeed, it may seem that Lanzmann is exploiting the “survivors, forcing them to reopen old wounds for what he believed would be the definitive film about the Holocaust” — but, Peary asserts, “because it is not, what they go through for him isn’t worth it.” Lanzmann “also speaks to former Nazis, a Polish train engineer who transported Jews to Treblinka: … and the people who lived by the camps.” He points out that “what is most terrifying is that these people would [seemingly] not protest the roundup and extermination of the Jews if it happened again” — unless, perhaps, it’s to protest the trauma they are put through in having to watch such atrocities occur; as one bystander casually notes:

Peary calls out a particularly “revolting” scene in which the “one survivor of Chelmno stands with his Christian ‘friends’ outside a Roman Catholic church” and hears how “the people didn’t like the Nazis but still talk about how God intended Jews to be punished for what happened to Christ.” Peary argues that while the survivors suffer in telling their tales, “we viewers do benefit from each recollection, each harrowing detail about the slaughter. And the obsessive Lanzmann insists on details: we get exact accounts of what happened, involving the amount of time prisoner trains took to reach the camps from their destination, what the prisoners were wearing, [and] how they were greeted by the Nazis at the camp.” Peary adds that while the “first half of the film contains much unforgettable material, [the] second half goes off on too many tangents (i.e., a long recollection about the Warsaw ghetto)” and “by the end you’re sick of Lanzmann (who often acts like Mike Wallace at his worst) and his techniques.” He concludes that this film remains “important viewing, but not consistently powerful, though it should be, considering its subject.” I disagree with Peary on several of his points: I don’t think it’s up to us as viewers to say whether it was “worth it” for the survivors to be pushed in the way they were, and I don’t believe Lanzmann becomes annoying. Meanwhile, the “tangents” in the final portion of this lengthy film serve as an invaluable back-story for everything we’ve seen and heard until then: by starting with footage of the death camp sites, then moving back and forth in time and space to talk with various people who either participated in or saw what was taking place, we gradually build a collective sense of how this years-long genocide unfolded. Indeed, Lanzmann is incredibly clear about what he’s determined to document, and refuses to compromise on his vision. Once you give in to the fact that this film 9 1/2 hour film will not relent — instead forcing you to watch, listen, absorb, and make sense of people’s memories without the mediating support or distraction of historical visuals — you begin to appreciate what Lanzmann is doing, and how, and why. Quotes from participants become seared into your brain:

In response to a question about his stylistic choice to not show any archival footage or stills, Lanzmann at one point noted that not a single photo actually exists of activity within the death camps — so, the only way to try to document this historic atrocity s to talk with people who were there. And if hearing Nazi bureaucrats discuss the logistics of exactly how the death camps operated doesn’t convince you, then what will? Take, for instance, this excerpt from Lanzmann’s interview with war criminal Franz Suchomel (being filmed secretly from a van parked outside):

This lengthy narrative is followed immediately by interview clips with Jewish survivor Filip Müller, who describes what it was like to enter the incineration chamber in Camp 1 at Auschwitz and engage in disposal of corpses for hours on end — in his case, “doing the work” instead of “choosing” to be shot. Suffice it to say that there is nothing in existence comparable to this documentary, which remains not only essential (albeit grueling) viewing for film fanatics, but an invaluable archive of facts that — shockingly — continue to be refuted and denied by some. Please do make the time and energy for it, though I recommend chunking it out into more manageable sessions (perhaps four). Redeeming Qualities and Moments: Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |

2 thoughts on “Shoah (1985)”

A must-see.

I saw this film when I first returned to NYC after living in Tokyo for a decade. My bud Tom (who was an NYU professor) would sneak me into the library with him so that I could watch library films during the day. I watched the film over the period of a few days on VHS. So I agree that it’s probably easier to watch while “chunking it out into more manageable sessions (perhaps four).”

It’s a grueling watch and mandatory viewing.

I also agree with the following: “I don’t think it’s up to us as viewers to say whether it was ‘worth it’ for the survivors to be pushed in the way they were, and I don’t believe Lanzmann becomes annoying.”

Although it’s not a film I think I am ever likely to rewatch, the reason for that hinges on ‘How could I?, or anyone?’ It’s not like it’s a film you ever forget, once you’ve seen it. I haven’t forgotten it to this day.

Interestingly, as I was re-watching parts of the film to prepare my review and gather quotes, I found myself caught up all over again in certain scenes –which I believe speaks to the power of the work Lanzmann produced here. It’s compulsive viewing.