Shining, The (1980)

“Some places are like people: some shine, and some don’t.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

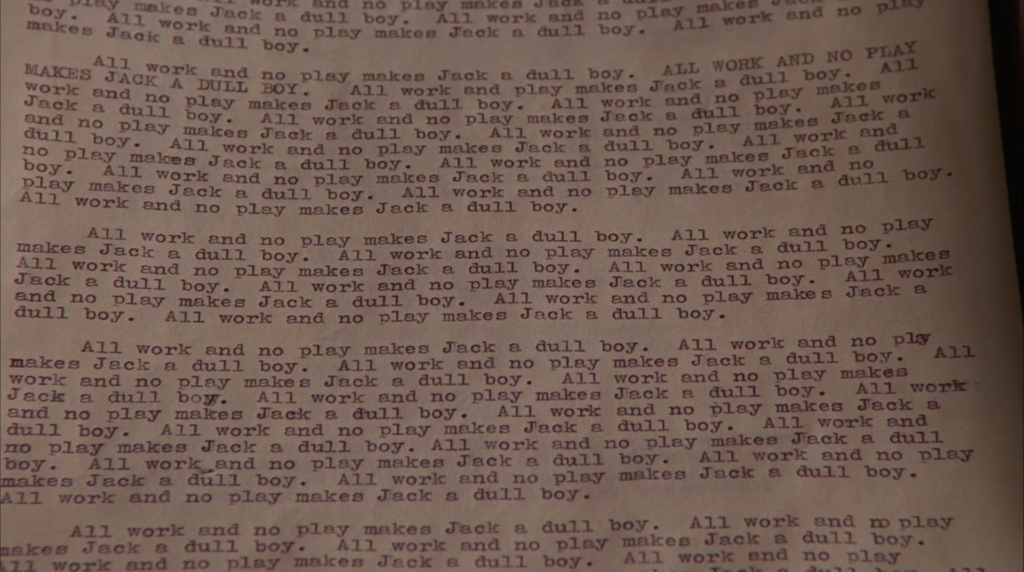

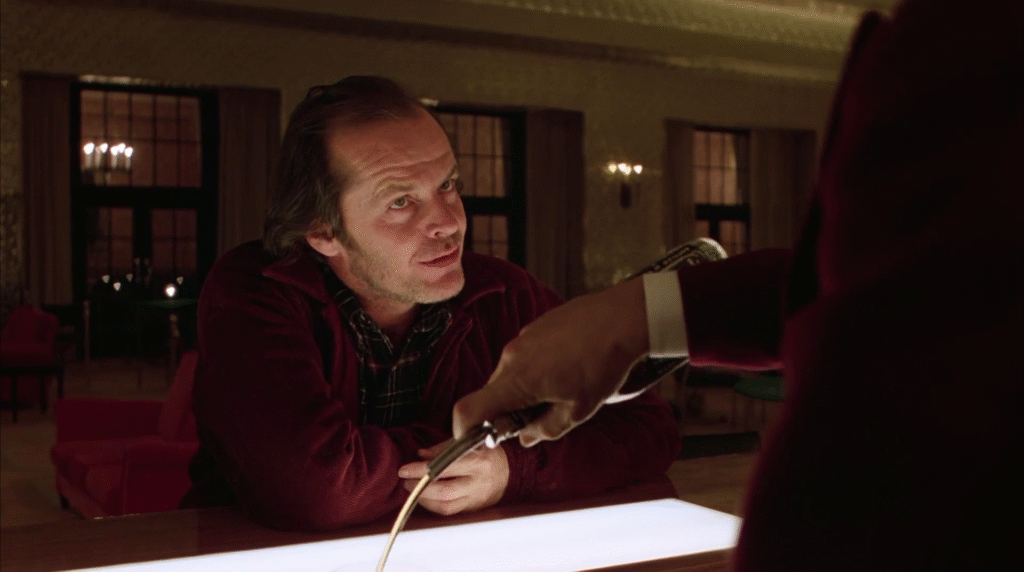

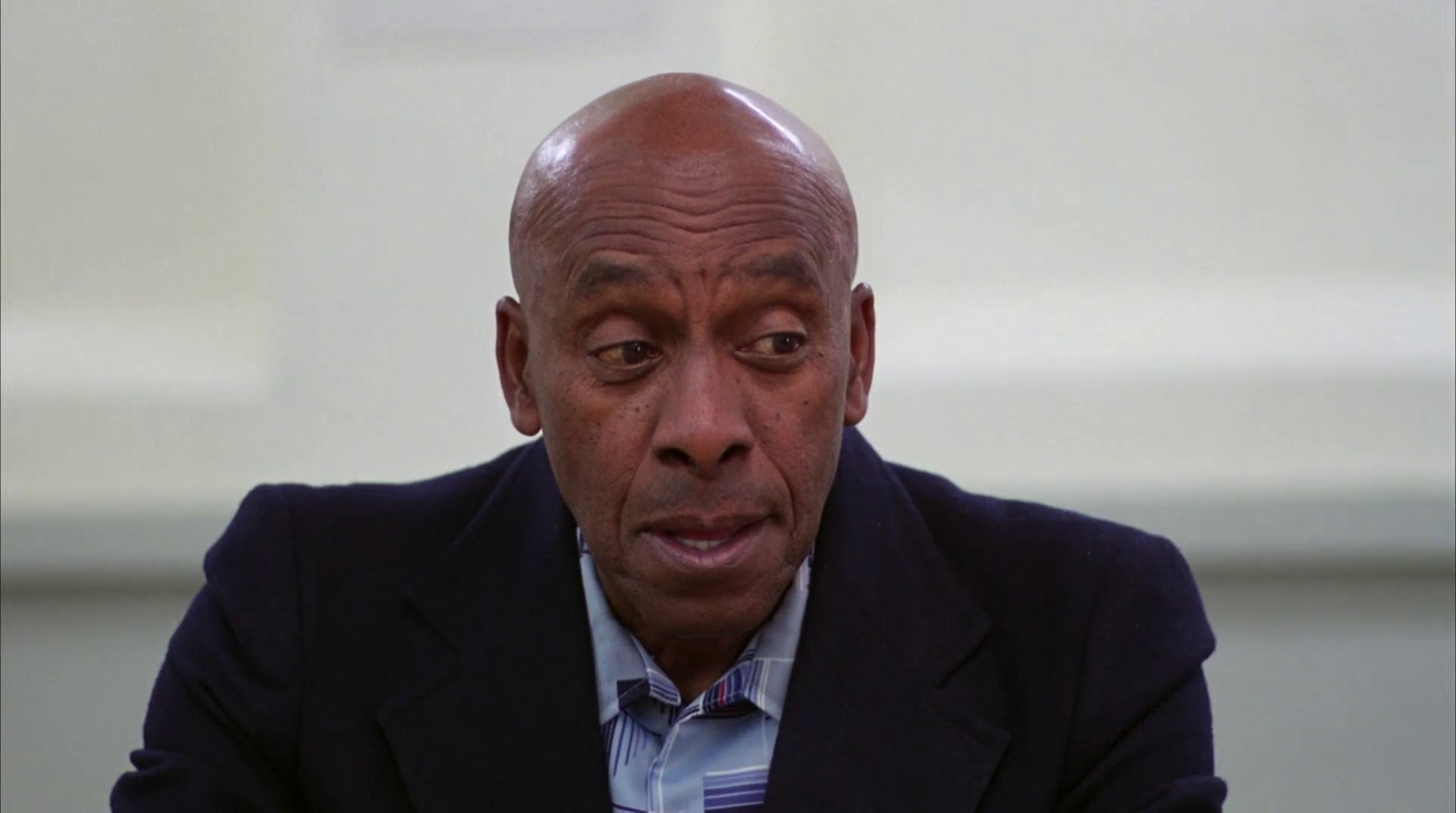

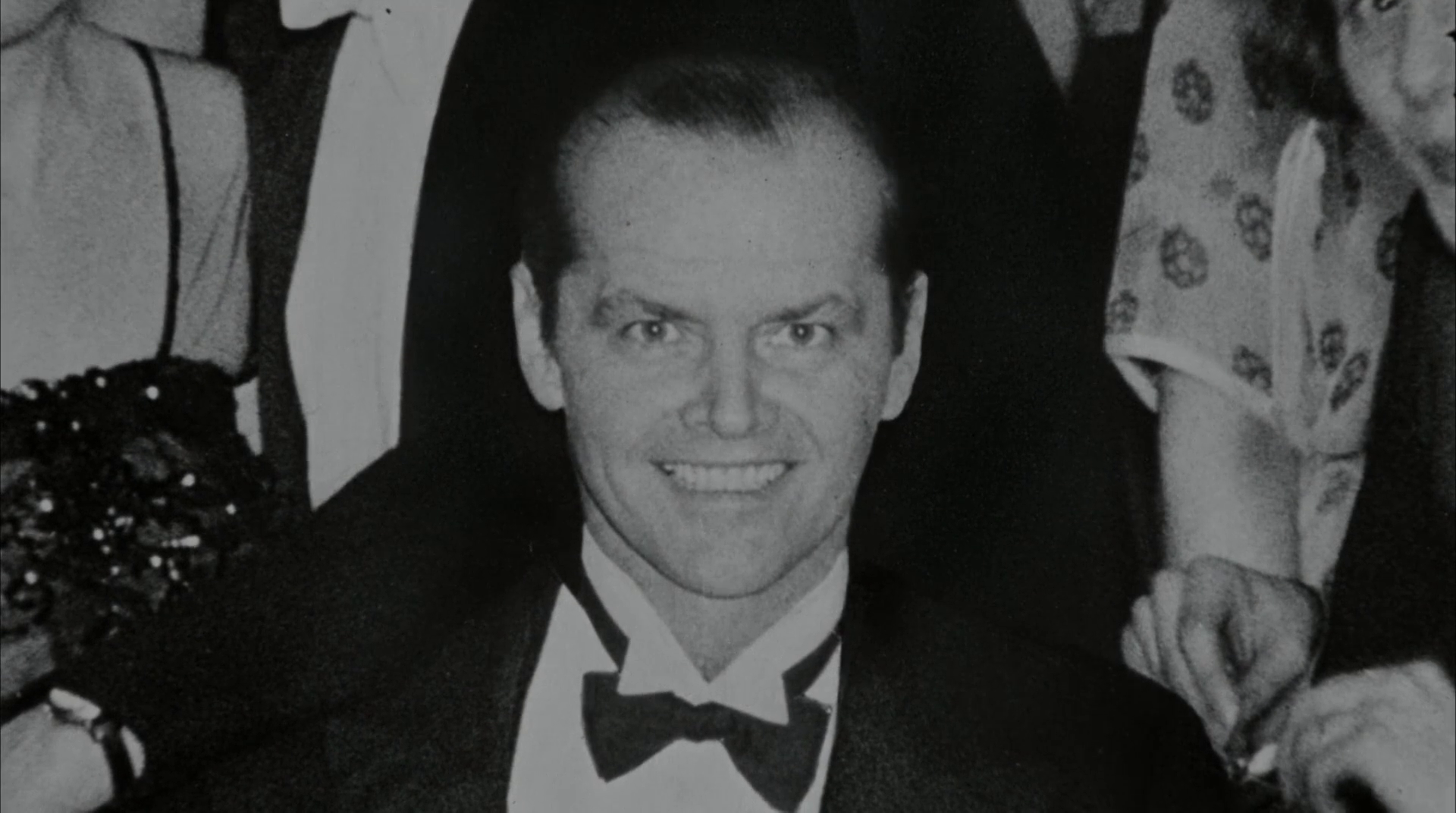

Response to Peary’s Review: Peary argues that “for us to fully grasp Danny’s primal fear that his father will turn on him and his mother, it’s important that the father begin the story as a sympathetic, loving father and husband” — though I’m not sure I agree with this assessment. Much to King’s stated chagrin, Kubrick most definitely made this story his own — but within the logic of Kubrick’s interpretation, it makes sense that Lloyd’s fear of his father (who abused him sufficiently to prompt him to stop attending school) would simply intensify upon moving to an isolated house away from the rest of humanity. Peary posits that “Nicholson’s crazed performance begins to wear on one’s nerves, no matter how remarkable it is at times” (I would agree), and that “by [the] picture’s end, one realizes that Duvall has outacted him” (well, she certainly gives a powerhouse performance — perhaps the best of her career!). Peary concedes that “there are scary things in the movie — the appearance of the dead twins: … Duvall reading her husband’s lengthy manuscript and discovering that it’s proof positive he is insane: … Nicholson chasing his son through the outdoor maze with an axe”: — and he writes that “for a while it is both powerful and creepy”. But he believes that “the moment Nicolson talks with the ghost bartender, the picture loses its grip,” and “from then on everything comes across as absurd.” Peary also hates the famous final shot, arguing that it’s “a terrible choice” and illustrates that “neither Kubrick nor his co-writer, Diane Johnson, was familiar enough with horror films to know what were the cliches of the genre.” In the film’s favor, Peary notes that “as do all Kubrick pictures, this one (in which he employed a Steadicam) looks great — better, in fact, than all other horror films”, and that Kubrick’s “familiar mannered, intentionally rapid dialogue (in which everyone uses the other person’s first name repeatedly) does create tension.” Given what a tremendous fan base this film has — an entire documentary, Room 237 (2012), is devoted simply to various potential explanations of underlying themes — it’s impossible to deny its importance in cinematic history. Like Peary, I appreciate much of the craftsmanship on display in The Shining — and unlike Peary, I’m not upset about the numerous significant shifts from King’s novel (which I haven’t read); I believe viewers should watch this film as part of Stanley Kubrick’s oeuvre, rather than as a “King adaptation”. However, I’ll admit to not being a huge personal fan of the film, simply because the pacing seems off (it takes more than half an hour for the family to finally be left alone in the hotel), and Nicholson’s psychopathic character is so utterly unlikable and obnoxious from start to finish that he’s challenging to watch for so long. I do recommend that all film fanatics give Room 237 a look, simply to take a deeper dive into what might possibly be going on in Kubrick’s meticulously planned storyline (is the shift in typewriter color an accident of continuity, or intentional? what is the significance of Danny’s Apollo USA sweater?). Agree or disagree with the views espoused, you’ll surely begin to understand the depth to which many people obsess over this movie. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |

2 thoughts on “Shining, The (1980)”

Agreed but, to me, it’s just a once-must for its status as a cult classic. It’s just too high-profile to ignore.

That said, it’s not a film I like much and my thoughts on it are brief. Although, as always, one has to see a source novel and a film as two completely different things, I find this a case in which the two are hard to separate.

I read the book. It scared the *crap* out of me (very much like ‘Salem’s Lot’ had done). So it was very difficult to take that feeling and stand it next to a film that simply seemed to… bungle it. It seemed that Kubrick had attempted something along more intellectual lines… something that the novel hardly needed; all it needed was to be made into an equally scary movie. To me, that didn’t happen.

That said, the film does have its isolated moments (it does have a great opening credits sequence) – the ones I recall having the most punch being the scenes between Nicholson and the bartender. But Nicholson does begin to go bonkers without all that much of a build, leaving his performance with few places to go.

Apparently Kubrick put Duvall, in particular, through a certain kind of hell. A number of her scenes work well (one, in particular, with social worker Anne Jackson – in which Duvall bizarrely and offhandedly reveals that her son gets hit fairly often). (This will be the film that audiences will remember Duvall for – but, personally, I think she’s better in ‘Three Women’.)

There are sequences which can come off as unintentionally funny (i.e., Crothers to Lloyd: “Do your parents know about… Tony?”; the woman in 237; Duvall happening upon the ‘monster bear’ giving the upper-class gentleman a blowjob, etc.).

Here’s a piece of trivia: I saw the film on its opening day, a Friday night in NYC. At that screening, the film had an extra scene at the end, in which hotel manager Barry Nelson tells Duvall something to the effect that Nicholson was simply missing, that “we went through the entire hotel and the grounds with a fine-tooth comb and we found *nothing*.” (cut to Duvall’s shocked face). That weekend, Kubrick cut that scene.

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️ out of ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Not terribly faithful but terrifying adaptation of the 1977 book. Really creepy and chilling even if Nicholson is too “out there” from the get go.

A definite must as an all-time classic.