Hardcore (1979)

“A lot of strange things happen in this world — things you don’t know about in Grand Rapids, things you don’t want to know about, doors that shouldn’t be opened.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

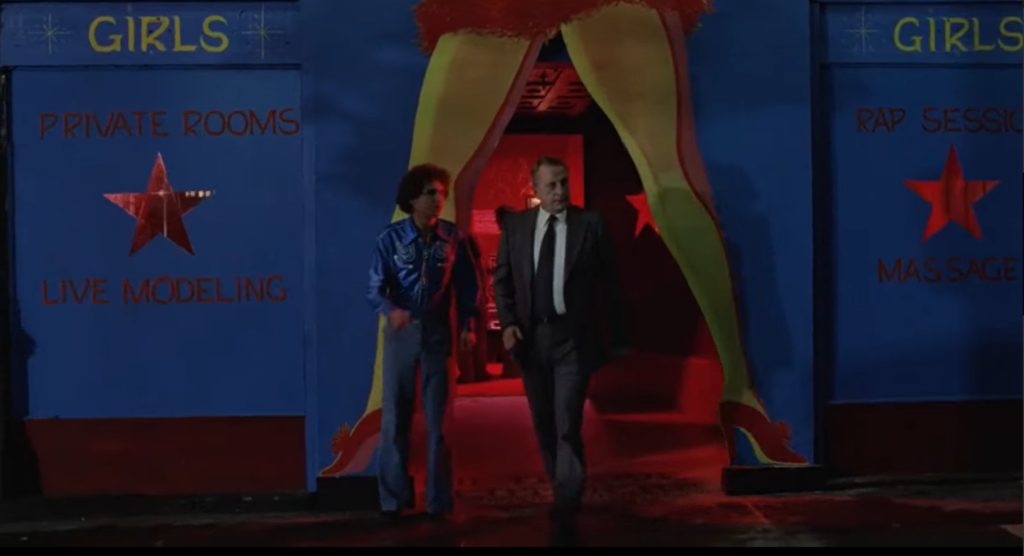

Response to Peary’s Review: — things slowly go downhill, as Scott’s months-long undertaking (why don’t we ever see him checking in on his business back home?) turns into simply a convenient pretext for “exposing” the underground porn and prostitution industry — an expose which these days no longer seems all that shocking. Scott’s performance is as fine and true as always, but his character as written doesn’t possess much of an arc — even once he begins opening up to a fresh-faced young prostitute (very nicely played by Season Hubley), we see little evidence of any real character transformation. The film’s deeply unsatisfying ending involves a sudden slo-mo action sequence (what happened to Schrader’s eye for naturalism?), an inexplicable shooting, and a cursory reunion between father and daughter. Given its intriguing premise and fine performances, Hardcore should ultimately have been much better than it is. Redeeming Qualities and Moments: Must See? Links: |

One thought on “Hardcore (1979)”

A once-must, tho I understand the reservations expressed.

I’m something of a Schrader champion. Admittedly, he’s made a few films that have missed the mark considerably. But, more often than not, his films are unique and compelling. ‘Hardcore’ is not a perfect film, but I feel it’s strong and solid enough for ffs to see – esp. for how it sits in relation to Schrader’s other films with the recurring theme of ‘the tortured outsider’.

Here, one might for a moment think that outsider is Scott’s daughter – but it’s Scott’s character; a man supposedly raised to have a deep and strong faith who nevertheless has been left unprepared re: how to treat people in anything but an austere (or, at best, semi-austere) manner. (His daughter’s eventual tirade at the end comes as no surprise when we recall an earlier scene in which Scott – in typical Midwestern manner – makes clear his distaste for a designer’s work while simultaneously superficially praising her. What the daughter reveals is her own distaste for her father’s non-stop mixed messages.)

I don’t feel Schrader is using his subject matter for the sake of exploitation. If you look at his overall body of work, his preoccupation tends to be with the underbelly of the human condition in general. Lead characters in his movies always struggle with something that could lead to their undoing, be it matters of the flesh, money, power, drugs, feelings of inferiority, actual placement of inferiority, etc. The ‘home’ of a typical Schrader protagonist is a deeply unsettled one.

Atypically here, the protagonist has no clue how unsettled his internal life is until he is forced to realize that. Interestingly, though Schrader seems to be indicating his own distaste for certain aspects of organized religion, he does so in a dispassionate manner – thus ultimately allowing us to feel for both father and daughter.