Giant (1956)

“We Texans like a little vinegar in our greens, honey — gives ’em flavor.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

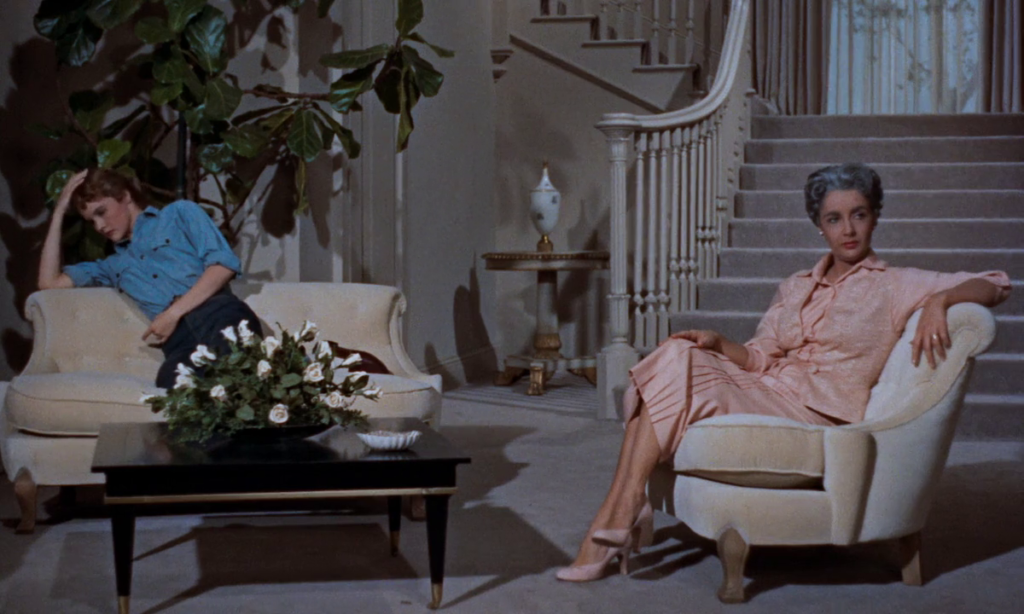

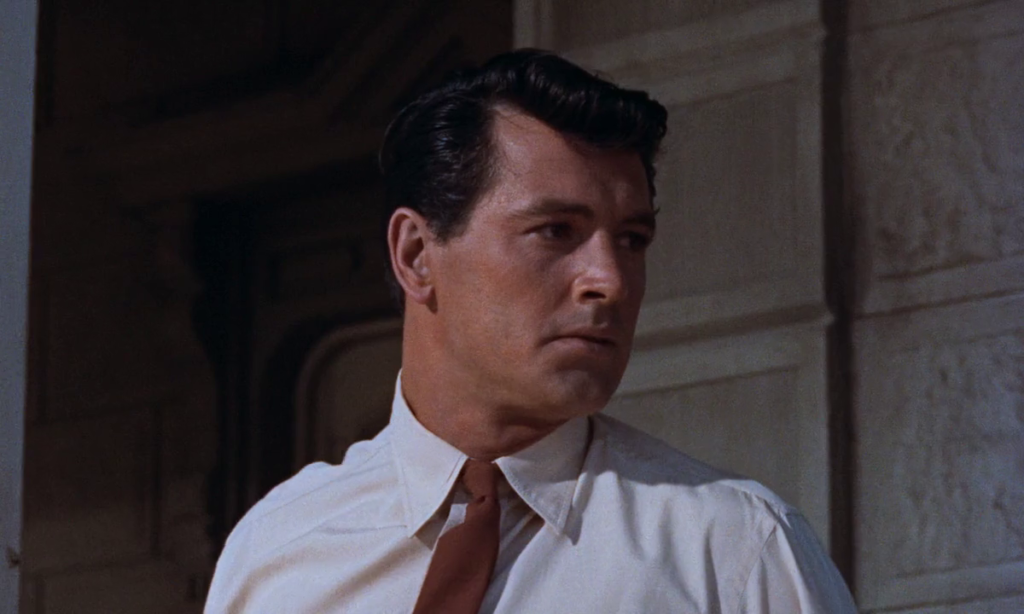

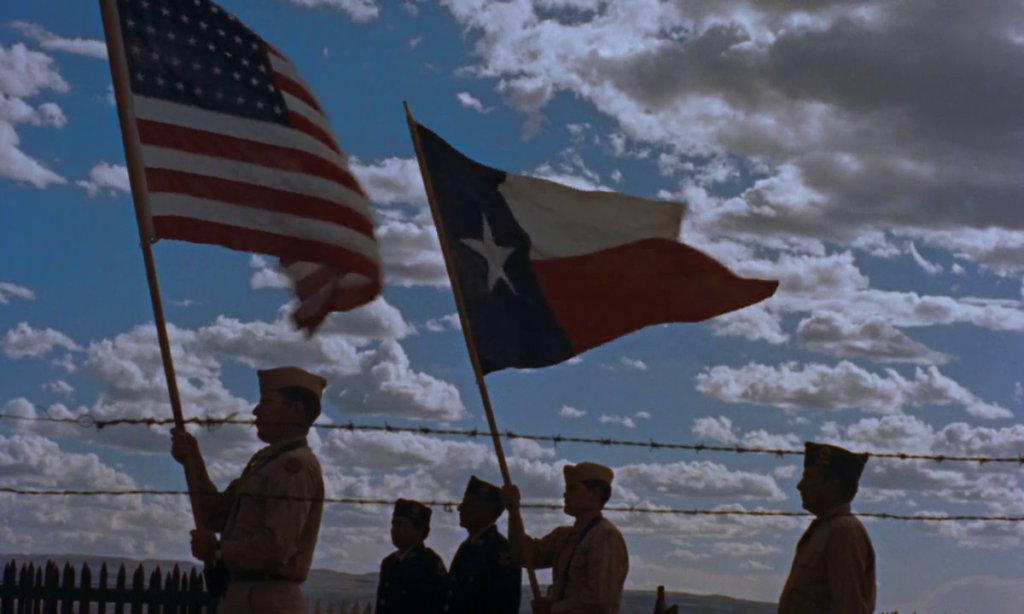

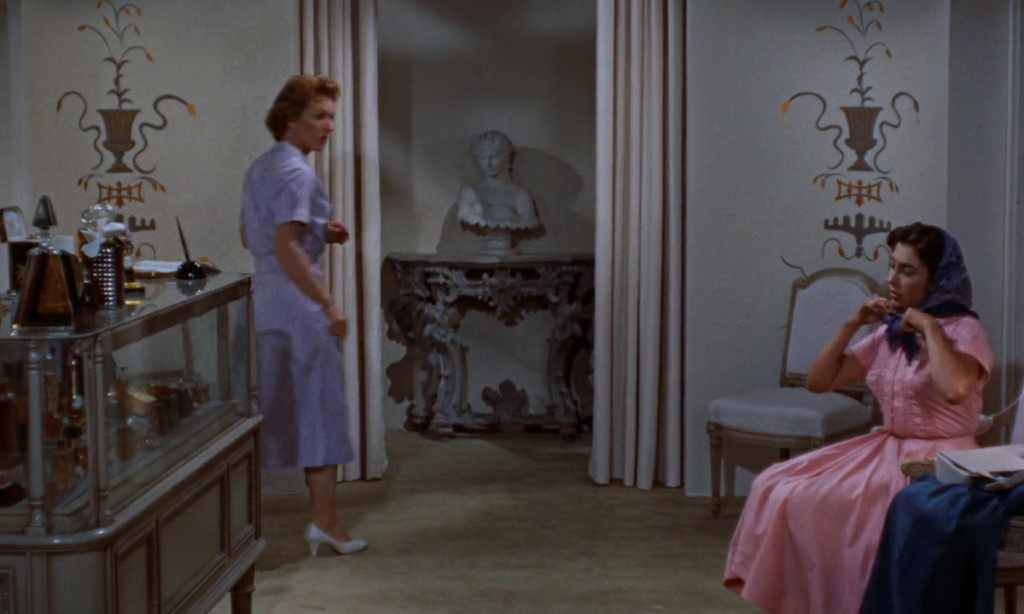

Response to Peary’s Review: With that said, I agree with Peary that a “particularly memorable” scene is the one “where he strikes it rich and gets covered by oil”: … though I’m less enamored by “the scene where [Dean] — now an older man — drunkenly recites a speech although his audience has long gone home.” Apparently Dean resisted having much aging make-up applied — though to be fair, it looks pretty awkward on Hudson and Taylor: Peary ultimately writes that “more interesting [than Dean] is Hudson’s character, who’s basically a nice guy but tries — without complete success — to cover up his gentle, soft qualities so he won’t seem weaker than his father”; however, since “it’s a new time in American history,” “men don’t have to strut their machismo to be giants.” Unmentioned in Peary’s review but of even more interest to me upon this re-viewing is Hopper’s character — a bold young man who knows what he wants (to be a doctor) and who he wants (Cardenas), and represents Taylor’s no-nonsense approach to equitable racial relations coming to full and personal fruition. Speaking of racial relations, the film’s most notable theme is that of racial intolerance — and the filmmakers deserve acclaim for presenting this in such a straightforward fashion. While modern social justice language isn’t used, we can clearly see white supremacy on dominant display time and again — from Hudson’s huffy refusal to acknowledge the theft of Texan land from Mexicans (one of Taylor’s first comments to him the night they meet), to his annoyance at Taylor humanizing their Mexican-American employees by seeking to know and correctly pronounce their names, to Taylor’s insistence that a doctor go look at a sickly “wetback” Mexican baby. In later scenes, we see even more egregious acts of racist segregation in 1940s Texas: a beauty salon refuses to serve Cardenas once they see her skin color (per orders of Dean); and, in the film’s penultimate scene, Hudson ends up in a fist fight with a bigoted cafe owner (Mickey Simpson) who refuses to serve a Mexican family and treats Hudson’s daughter-in-law and grandson with racist contempt. As Peary notes, this is a “terrific scene” — and though the “wide-screen production is patriotic,” it “still acknowledges that bigotry is widespread.” Peary closes his review by noting that while the “film has slow and hackneyed scenes,” it’s “quite enjoyable.” Sadly, I can’t really agree: while it’s worth a look for its historical popularity, it’s not one I personally plan to revisit. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories (Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |

One thought on “Giant (1956)”

A once-must for its place in cinema history.

I’m in general agreement with the assessment given. For all its epic sprawl, it’s not the most exciting of pictures – certain scenes have more impact than others; it’s often content being quiet and sharply observational and there are particular moments of visual beauty. One of the most potent sequences is the penultimate restaurant scene. The film’s main value seems to rest in its re-creation of a specific time / place / culture… and that culture’s shifts. Personally, I enjoy watching Taylor (esp.) and McCambridge in it.

Wikipedia tells us: “‘Giant’ won praise from both critics and the public, and according to the Texan author, Larry McMurtry, was especially popular with Texans, even though it was sharply critical of Texan society.”