“I must know what’s going on: who am I?”

|

Synopsis:

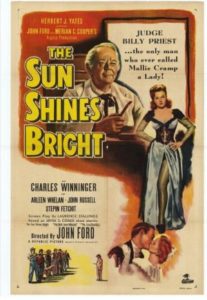

With help from his loyal servant (Stepin Fetchit), a Southern judge (Charles Winninger) defends the rights and dignities of the downtrodden in his town, including a young black man (Elzie Emanuel) falsely accused of rape and a newly repatriated sickly prostitute (Dorothy Jordan). Meanwhile, a beautiful southern belle (Arleen Whelan) is courted by a handsome young man (John Russell) who is unaware of her true parentage, and who battles on her behalf against a local bully (Grant Withers).

|

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Deep South

- John Ford Films

- Judges

- Mistaken or Hidden Identities

- Morality Police

- Prostitutes and Gigolos

Review:

John Ford’s follow-up to his 1934 film Judge Priest — based on characters in several short stories by Irvin S. Cobb — was, along with Wagon Master (1950), purportedly one of Ford’s personal favorites. It tells a meandering if ultimately coherent tale of numerous small-town events, all centering around morality and the need to stand up for the innocent and unfairly maligned. Unfortunately, the film’s morals come across as decidedly problematic, given that Fetchit is reduced yet again to playing a typically servile, lazy, incomprehensible, and fumbling Black companion, while Winninger’s defense of Emanuel posits him unambiguously as the town’s necessary White Savior. This is especially ironic given an extended sequence early in the film — one seemingly included as character enhancement rather than to further the plot — in which Winninger celebrates his former role in the Confederacy. While the final funeral procession does arouse one’s emotions, it seems to come at the cost of a misremembered sense of chivalry, nobility, and racial justice — ideals that have yet to manifest in our nation.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Atmospheric cinematography

Must See?

No; you can skip this one unless you’re a Ford completist.

Links:

|

One thought on “Sun Shines Bright, The (1953)”

First viewing. A once-must (with reservations), for its place in cinema history. As per my post in ‘The ’40s-’50s in Film’ (fb):

“And the scribes and Pharisees brought unto Him a woman taken in sin…”

‘The Sun Shines Bright’ (1953): To appreciate what director John Ford called one of his favorite films (if not his actual favorite), it’s necessary to separate the wheat from the chaff – something one must do with some other Ford films as well. But if certain aspects of ‘TSSB’ are contradictory, they also mirror the mass of contradiction that was Ford himself… all of which is largely documented (it makes for fascinating study) and is easily found. (For example, he was a professed socialist Democrat, yet he went from being a JFK fan to being a Nixon supporter.) Occasionally, the ‘split’ seems so pronounced – and ‘TSSB’ is a case in point – that some people just want to avoid a particular film altogether, in ‘baby with the bathwater’ fashion. However… this film has rewarding merit. Yes, it reflects racism in its depiction of blacks – and, yes, it offers up a protagonist (a judge, played with gusto by Charles Winninger) who is sentimental (to say the least) about The Old South. But it also has some memorably startling sequences which, in relief, serve to mitigate the film’s flaws. I’m referring specifically to three standouts: an anti-lynching scene (which, years later, will echo in ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’); the near-reunion of an estranged mother and daughter; an extended funeral procession which simply yet boldly builds in remarkable power. ‘TSSB’ is significant, in general, for its focus on women – something Ford did not often do; his films almost always traffic in uber-masculinity. (In her autobiography, Maureen O’Hara mentions that she once walked in on Ford kissing a male actor that she didn’t name. Does that partially explain his rare highlighting of women?) … With ‘TSSB’, Ford wanted to remake his 1934 film ‘Judge Priest’ because the attempted lynching content in the first film had been cut. When ‘TSSB’ was released, its producer had, in turn, cut over 10 minutes (mostly character-establishing material) – which was much later restored when a full print was found.