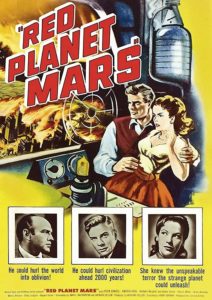

Red Planet Mars (1952)

“Our economic system is a shambles — industrial production shot to blazes — our entire civilization collapsing about our heads like a house of cards, and the whole western world going down with us.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres:

Review:

Unfortunately, while its title promises vibrant color, the only “red” in this black-and-white flick is Communism, personified as villainous bad guys with an unwilling hostage (Calder) in their hands. When the primary theme of the film is revealed: … we’re meant to believe that if only all humans were free to practice Christianity, we would be lovingly at peace with one another. Naturally, nothing is ever this simple, though it’s fascinating to see what audiences once-upon-a-time may have been wishing for. Redeeming Qualities and Moments: Must See? Links: |

One thought on “Red Planet Mars (1952)”

First viewing (8/18/19). A once-must for camp / cult film fans with a sci-fi leaning. As per my post in ‘The ’40s-’50s in Film’ (fb):

“And you’ll have done it. You’ll be the next to advance science – and maybe us – right into *oblivion*!”

‘Red Planet Mars’ (1952): Taking a tip from his young son, an astronomer (Peter Graves) finally manages to communicate with the people of Mars by using the value of pi to establish intelligence (um… ok… ). Anywho… once you get beyond that and a bunch of other scientific mumbo-jumbo, ‘RPM’ establishes itself as a by-product of the era of McCarthyism (1950-54), when apparently there was a marked increase in spiritual matters, as a panacea to counteract the human hysteria of the time. (See also 1950’s ‘The Next Voice You Hear’ and 1951’s ‘The Day the Earth Stood Still’.) One of several messages transmitted to Earth is that Mars is so far advanced (relying almost purely on ‘cosmic energy’) that it basically resembles the nirvana of Heaven. (It seems God lives there as well.) Such news first causes a dual worldwide panic – but then there’s an unforeseen shift. ‘RPM’ walks a fine line between earnestness and silliness – both of those elements resting firmly in the performance of famous acting guru (and husband of Uta Hagen) Herbert Berghof as an ex-Nazi scientist mainly responsible for the means to interplanetary communication. (Impressively, Berghof does prove that it’s possible to act just about *anything* if it’s done with conviction.) Viewers of this film tend to be squarely split: some find it to be either intellectually offensive or on the level of an Ed Wood film (which isn’t really fair – although, yes, I did occasionally giggle); others recognize it as a ‘logical’ reflection of the Cold War-era. You decide.