|

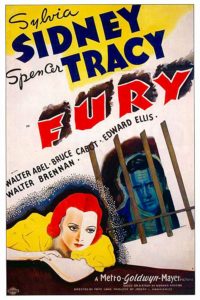

Genres:

- Character Arc

- Courtroom Drama

- Falsely Accused

- Fritz Lang Films

- Living Nightmare

- Revenge

- Spencer Tracy Films

- Sylvia Sidney Films

- Walter Brennan Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

Peary writes that this “frightening social drama” — “Fritz Lang’s first American film” — “gave Lang the opportunity to advance several of his most important themes: it is unsafe to be a stranger in this world”, given that “people are very territorial; when townspeople band together they may turn into a mob; a man’s innocence or guilt is not what determines how a jury or a mob will judge him; [and] there is no such thing as justice” given that “a hero who seeks revenge and continues the violence initiated by the villains becomes as bad as they, because to play on their terms he relinquishes his humanity”. While Peary points out the “ending is disappointing”, this remains “one of the strongest indictments of America’s small-town lynch-mob mentality.” The film is too nightmarishly surreal at times to be considered strictly realistic — Tracy’s flipped-switch character is a precursor to his role in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1941); most of the townspeople are caricatures — but the sentiments and morality behind this living-nightmare flick remain scarily authentic. Mob violence is no joke, and continues to cause untold misery across the globe; surely few knew this better than Lang at the time, who had just fled from Jewish persecution in Nazi-occupied Germany.

With that said, it’s important to note that this film was thoroughly whitewashed in order to be more palatable to white audiences of the day; according to TCM’s article:

The story was conceived during a shocking time in American history when lynching and mob violence escalated in the early 1930s. The fires of injustice were further stoked when a federal anti-lynching bill drafted by NAACP lawyers was killed by the U.S. Senate. But with his hands tied by the notorious movie censorship of the studio years, Lang was unable to explicitly treat lynching as a crime against black people. Lang was even forbidden to use black actors as minor characters in the film, though he initially shot several scenes featuring peripheral black characters to subtly drive home the idea of lynching as a threat to black Americans. In one deleted scene, a black laundress sings a song of freedom as she hangs out the wash, and in another a crowd of Southern blacks is shown responding to a radio speech by Fury‘s district attorney condemning lynching. Both scenes were cut from the film at the studio’s behest.

Clearly another, more authentic film remains to be made about the true horrors of lynching against black Americans in early 19th century America.

Note: Fury was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress in 1995 for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Sylvia Sidney as Katherine

- Spencer Tracy as Joe Wilson

- Atmospheric cinematography

- The truly frightening mob scene

Must See?

Yes, as a still-powerful indictment of mob brutality.

Categories

Links:

|

One thought on “Fury (1936)”

A once-must, for its place in cinema history. A particularly strong film from Lang – and it remains a cautionary tale. ~though it would never be easy cautioning a mob intent on following a mob leader.

Once news of Tracy’s capture gets out to the public and a stream of gossip quickly begins, I was reminded of the stirring sermon given (by Philip Seymour Hoffman) on the insidious nature of gossip in John Patrick Shanley’s ‘Doubt’.

More than that – I kept thinking of the spirit of mob mentality that rests within the current White House administration and the hearts of its followers. Of course, unlike in this film (which at least has the mob following a genuinely angered sense of justice), what is happening in our country is the growth of a political mob dead-set against genuine justice – in favor of anarchic mob rule. They operate differently than what Lang depicts but it amounts to the same thing – and it still ends up killing people, only in different ways.

This film’s value – in one form or another – may be a now and forever thing.

Note: The black laundress appears in the version I just watched – and seems clearly recognizable as Ethel Waters.