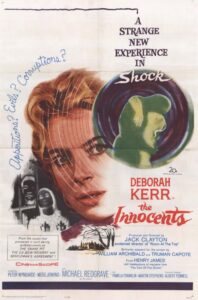

Innocents, The (1961)

“They must be made to admit what is happening — one word, one word of the truth from these children, and we can cast out those devils forever!”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Review: The performances in The Innocents are, across the board, superb. It’s difficult to imagine anyone better than Kerr at playing Miss Giddens, an idealistic, faithful, sexually repressed woman who is mortified to learn that her sweet charges may have been corrupted — and who will stop at nothing to “clear” them of their sins. Both Pamela Franklin (who, six years later, starred in Clayton’s Our Mother’s House) and Martin Stephens (from Village of the Damned) are entirely believable as the inscrutable siblings, and Megs Jenkins rounds out the cast beautifully as the children’s well-meaning, naive maid — her performance never hits a false note, and is essential to the success of the story. Equally impressive are the film’s visuals, including the stunning black-and-white cinematography, appropriately baroque set designs, and effective use of pastoral outdoor settings. Much like in Robert Wise’s The Haunting (1963) and Val Lewton’s early films for RKO, the frights here are cinematically suggested rather than made explicit, with Clayton using a variety of techniques (including deep focus framing and double exposure) to evoke horror; yet even some straightforward shots — such as a bug crawling out of a statue’s mouth — are enough to cause one to jump. Ultimately, the “horror” here is truly psychological, indicating that the worst monsters are the ones we — like Miss Giddens — conjure up for ourselves. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

Links: |

One thought on “Innocents, The (1961)”

An absolute must! And easily lends itself to (indeed, to be best appreciated, may even require) multiple viewings.

I’ve just rewatched this as a blu-ray – a very nice upgrade.

On the DVD disc are three very informative extras about the making (and makers) of the film. Helpful to know: The film is based on William Archibald’s play – which director Clayton was not all that fond of, since it was difficult to make it work…as a film. Writer John Mortimer was brought in to ‘Victorian-ize’ the dialogue. At one point, Capote was brought in…and that made most of the difference for the actual film, since Capote (who Clayton credits for about 90% of the working script) reworked the script with a Freudian/Southern gothic sensibility.

Much is made about whether or not the crux of the story is a figment of the governess’ imagination. Clayton himself said he intended the film to be ambiguous and, therefore, open to interpretation – the open-endedness of which does result in a more powerful film (rather than everything being spelled out).

On one hand, I understand the inevitability of the story being read as the ‘ravings’ of a repressed or vulnerable mind. (The same logic was placed on Rosemary in ‘Rosemary’s Baby’.) But for me, personally, I don’t find that interpretation as satisfying. Why must the main character (either the governess or Rosemary) be vulnerable or weak or repressed? Why can’t she – as an intelligent woman – simply be suddenly thrown into the world of the supernatural (for real) and deal with that as such? I think that works much more effectively as a narrative – if the woman *does* actually have her wits about her but, nevertheless, finds herself in the midst of (and subject to) an uncontrollable/unstoppable force.

In my reading up re: the film, very little is ever made of Michael Redgrave as ‘The Uncle’ – but, when you listen to Redgrave’s character speak, you can’t help but think he is gay. Keep in mind that the uncle (although a small part) has been filtered through Capote. Also, Redgrave (who once stated he was bisexual) seems to be playing the role as though he is a more contemporary version of Ernest Worthing (the character in ‘The Importance of Being Earnest’ that Redgrave played in that film version). It’s intriguing, to say the least.

But, of course, there’s no forgetting or overlooking the main cast – who are, in the assessment and just about everywhere the film is written about, all properly deserving of the praise they have all received.

~as is every aspect of this nearly perfect film: acting, direction, script, photography, production design, score, etc. I say ‘nearly’ because how perfect you find the film depends entirely on how much you give yourself over to it. If you don’t doubt the credibility of any of it for a second, then you may very well find the film to be…perfect.