|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Anthony Quinn Films

- Biopics

- Cross-Class Romance

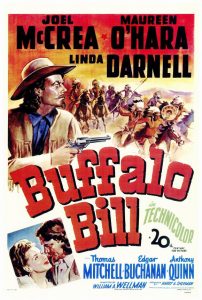

- Joel McCrea Films

- Linda Darnell Films

- Maureen O’Hara Films

- Native Peoples

- Thomas Mitchell Films

- Westerns

- William Wellman Films

Review:

William Wellman’s biographical western of William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody is an interesting attempt to add nuance and authenticity to a “cowboys and Indians” shoot-em-up flick, but ultimately doesn’t quite succeed at its goal. According to Jeff Wilson’s review for “Digitally Obsessed”, Wellman himself noted that the film was:

…meant to be a more cynical look at the legend of Buffalo Bill, but as Wellman described it to Richard Schickel in The Men Who Made the Movies, his co-writer decided that he didn’t want an American legend to be destroyed in that fashion, so the script was discarded and this more sanitized version was produced. Wellman was somewhat ashamed, as he put it, of the finished product, in particular the end.

Cody is shown as generally sympathetic and supportive of Indian culture (and concerned about too many bison being slaughtered), but it’s hard to tell fact from fiction, especially given the critical intervention of ultimate storyteller and myth-maker Ned Buntline (Mitchell) into Cody’s life.

The film’s most discomfiting scenes feature Darnell as an Indian princess who is openly jealous of Cody’s crush on O’Hara (thus adding a bit of “love triangle” tension to the film). In one scene, she helps the semi-literate Cody write a response to O’Hara’s note, looking at him with baleful eyes as she repeatedly attempts to craft an appropriate signature on his behalf. Later, she sneaks into O’Hara’s room and tries on a gown:

O’Hara [entering her room and spotting Darnell in her dress, admiring herself in front of a mirror]: Who are you? [Darnell turns around.] An Indian! What do you mean by breaking into my room and stealing my clothes?

Darnell: I… I didn’t come here to steal.

O’Hara: Maybe you Indians have another word for it, but that’s my dress you have on.

Darnell: I tell you I didn’t come here to steal.

O’Hara: Perhaps you’ll explain to me just what you’re doing in my clothes!

Darnell: I wanted to find out something.

O’Hara: And just what, may I ask?

Darnell: I wanted to find out… if I could be as beautiful as a white girl… in a white girl’s way.

O’Hara [melts, as violins begin playing]: Oh… I see. [smiles and takes Darnell’s hand, showing her the mirror.] There’s your answer. You look beautiful. [beat] I wish your Indian brave could see you now.

Darnell [eyes widen in anger, as pulsing drumbeats re-emerge on the soundtrack]: Indian! [she tears off the dress]

O’Hara: What is it? What did I say to offend you? Please… I’d rather you kept it. It was so becoming on you.

Darnell: I don’t believe you! You don’t want it because an INDIAN wore it! [throws dress at O’Hara]. Indian! [said as she climbs out the window].

This scene could be deconstructed in countless ways — but suffice it to say that Darnell’s character is openly ashamed of being Indian, and only believes she can have worth (and Cody’s heart) by looking beautiful in a “white girl’s way”. Meanwhile, the entire romance between McCrea and O’Hara lacks conviction:

We’re not given much insight into why Cody would be so attracted to her other than her beauty, and their ongoing clash in lifestyles (who knew?!) simply serves as a predictable plot element driving narrative tensions forward.

Note: Nine years after his supporting role in Annie Oakley (1935) as Buffalo Bill, Moroni Olsen was cast in essentially a cameo role here as the father of the woman Buffalo Bill marries — a nifty touch for those keeping track.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Fine Technicolor cinematography

Must See?

No; feel free to skip this one.

Links:

|

One thought on “Buffalo Bill (1944)”

First viewing. Not must-see.

It can be all-but-impossible to take the side of a film that both its director and writer dislike. As noted at TCM’s site:

[(Writer Gene) Fowler thought Cody “the fakiest guy who ever lived,” and wanted to make a movie that would speak to the less-glamorous truth of the man’s life. Wellman liked this approach, and the two men spent months researching the real Buffalo Bill. Wellman later said that he and Fowler worked on a screenplay for three months, after which time they had “half a script that was absolutely beautiful.”

Then one evening, as Wellman recalled, Fowler phoned him to say he’d decided their approach was all wrong. “You can’t kill any of these wonderful heroes that our kids…and everyone else, worship and like,” Fowler said. “And that’s what we’re doing. Buffalo Bill is a great figure, and we cannot do it.” In other words, to destroy the legend of Buffalo Bill might have been interesting and truthful, but the moviegoing public would likely have none of it. …So the two men spent a drunken night tossing their script into a fireplace, one page at a time. “[We] burned up three months of the most wonderful work I’ve ever done with a writer in my whole life,” said Wellman. “[But] he was right.”]

Well, ‘right’ in the sense that the film they intended would have been a box-office flop. Audiences didn’t want the truth; they wanted the legend – and they proved that by making ‘Buffalo Bill’ a box-office hit. Wellman didn’t want to make the film but he was stuck – “he had no choice but to make the movie because he owed Fox a film for having been permitted to make ‘The Ox-Bow Incident’ (1943), a film that studio chief Darryl Zanuck disliked as much as Wellman disliked ‘Buffalo Bill’.”

As also (humorously) noted at TCM: “O’Hara, in fact, later wrote that she believed it was the Technicolor photography that made the film such a substantial box-office success.” O’Hara also disliked the film.

So, is it a bad film? Probably not – if you prefer legends. It’s a well-made film (and it does seem to make some admirable points) – but apparently it’s mostly hogwash.

TCM finally notes: Fox released ‘Buffalo Bill’ before ‘The Ox-Bow Incident’, and while the former scored box-office gold, the latter made no dent with moviegoers, though critics loved it. In truth, Zanuck hated ‘Ox-Bow’ so much that he barely released it, so it never had a real chance. But ‘The Ox-Bow Incident’ has since become regarded as one of the great classics of the era, while ‘Buffalo Bill’ is remembered mainly for its rousing battle scene and technical merits.