“About her, I know even less. I don’t understand what is between them.”

|

Synopsis:

A young man (Gosta Ekman) takes a job helping to organize the papers of a renowned philosopher (Lars Ekborg), and soon finds himself inextricably embroiled in Ekborg’s troubled marriage to a seemingly insane wife (Adriana Asti); when Ekman’s frustrated girlfriend (Agneta Ekmanner) appears at their house, relations get even more surreal and complicated.

|

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Marital Problems

- Scandinavian Films

Review:

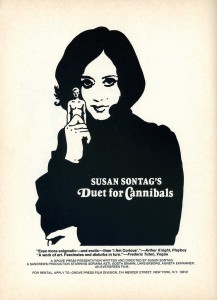

It’s no surprise that noted philosopher/essayist Susan Sontag’s directorial cinematic debut — a Bergmanesque psychological drama housed within a Bunuel-ian/Godard-ian surrealist framework — has nothing to do with actual flesh-eating cannibals; what’s disappointing, however, is how ultimately derivative and pointless her experimental vision is. While we’re kept intentionally in the dark about various characters’ motivations, it’s immediately clear that Ekborg and his wife are manipulative narcissists desperate to ensnare gullible subjects in their troubled marital web; the real question (for those involved enough to care) is why Ekman and Ekmanner allow themselves to become part of such a farcically dysfunctional drama. When trying to read a bit more about Sontag’s possible intentions with the film, I stumbled across the following quote in an analytical essay, in which Duet… is described as “a film that punishes you vindictively for threatening its existence by trying to interpret it away” — in other words, viewers should be forewarned that any director who previously published a collection of essays entitled Against Interpretation (1966) is not likely to create a movie that allows for easy or straightforward analysis. Ultimately, this one is exclusively for diehard Sontag fans; all others should be forewarned.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Occasional moments of head-scratching surrealism

Must See?

No; this one will only appeal to certain constituents, and isn’t worth seeking out by all-purpose film fanatics. Listed as a film with Historical Importance in the back of Peary’s book, though I’m not sure why.

Links:

|

One thought on “Duet for Cannibals (1969)”

First viewing. A once-must, as an enjoyable cult item.

Yet another Peary title which almost defies discovery; I’ve only now been able to happen upon it for the first time since it’s currently available on YouTube (though, it being YouTube, who ever knows for how long?).

The person who posted the film at YouTube attached the NY Times review, which followed the film’s premiere in 1969 at the NY Film Festival. What’s particularly amusing about the review is that it takes the film ABSOLUTELY SERIOUSLY (!), as if its intent is to be genuine cinema.

It isn’t. It can’t possibly be. In too many instances, the film is simply too funny to be interpreted as…um…art.

With its similarly claustrophobic setting and its focus on two heterosexual couples, it doesn’t take much to recognize the wonderfully titled ‘DFC’ as a parody of ‘Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?’ (released as a film three years earlier). It’s like watching Albee’s work rewritten and directed by Ingmar Bergman, with a slight dash of soft porn director Joe Sarno thrown in. The main difference here is that the Nick and Honey characters of ‘VW’ are seen less as mere punching bags; instead, they each become sexually involved with the main couple. (Sontag was bisexual. The sex in the film is not explicit and though there’s a hint of lesbianism, male homosexuality is absent.)

‘DFC’ is basically ridiculous. A look at Sontag’s Wikipedia bio reveals the following quote: “…it’s never been my prime mission to give comfort, unless somebody’s in drastic need. I’d rather give pleasure, or shake things up.” That’s what Sontag appears to be doing with this film – pleasurably shaking things up. The film is something of a slight fever dream which, though mostly played as realism, regularly delves into the absurd. For example, at one point, rather than confront each other verbally, the two male leads take turns ‘talking’ to each other by writing on a blackboard (!); and much of the dialogue hangs on the edge of hilarity (the strangely sexy Ekman to his wife: “Now listen! I’m going to do one of three things: I’ll beat the hell out of you, walk out with you or leave here alone. You can choose. …Which is it to be?”) – and let’s not overlook the scene in which Asti challenges Ekman to watch her making love to her husband in a car…while she simultaneously completely covers the front windshield with what appears to be shaving cream. …There are other scenes of unexpected ‘delight’ as well.

Sontag is not working with amateurs here – the four leads have fairly accomplished resumes (oddly, Ekborg died the year of the film’s release, at age 43), so the whole thing is played with earnest conviction and it’s not boring in the least. It will be appreciated most by those who take it as the lark that it is. It’s certainly not the best of cult films – but considering this film is the work of the writer who gave us ‘Notes on Camp’, it’s not to be ignored.

Note: FFs unfamiliar with Sontag can also see her in a charming cameo appearance in Woody Allen’s ‘Zelig’.