|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Burt Lancaster Films

- Gena Rowlands Films

- John Cassavetes Films

- Judy Garland Films

- Mentally Retarded

- Paul Stewart Films

- Teachers

Review:

Judy Garland’s next-to-last film — one of just two studio pictures directed by independent filmmaker John Cassavetes — is a well-intentioned but ultimately patronizing, dated, and frustrating affair. It shows just enough evidence of Cassavetes’ famed cinéma vérité style (through footage of actual children at the school where the story takes place) to frustrate viewers hoping for much more of this:

Meanwhile, the storyline itself is purely calculated drivel all the way. One would think that Garland, close to the end of her tragically drug-addled existence, would be well-suited for the lead role, playing a musician desperately seeking some kind of meaning in her life (rumor has it that Garland loved children in general, and children with disabilities in particular) — but her character is frustratingly shallow here; all we learn about her is that she’s an unmarried, well-trained musician.

Meanwhile, she’s allowed to come work at the school despite possessing no credentials other than her own good intentions — and even once she’s hired, we simply see her wandering the grounds for the majority of the film:

until she’s finally tasked by Lancaster to actually teach the music classes she claimed in her brief interview that she wanted to implement; ultimately, her character comes across as simply one more “case” for Lancaster to explore (though this angle isn’t sufficiently exploited, either).

That a mid-century-Hollywood “issue” film like this comes across these days as horribly dated is no surprise, and shouldn’t necessarily be a deal-breaker for would-be viewers. Fortunately, at least in the United States, we’ve moved beyond the well-intentioned but utterly corrupt notion that children with mental retardation (now referred to more properly as students with intellectual disabilities) are best served by being separated from their families and taught to live “independently” in a group home with others; in one climactic “horror scene”, we’re shown older MR individuals (clearly in a state of blathering incapacity) who were apparently allowed to stay at home with their parents for too long, and consequently were left helpless and without appropriate skills by the time they were finally institutionalized as adults (!!). While surely well-intentioned at the time, this scene comes across nowadays as voyeuristic at best.

Meanwhile, Reuben (well-played by Bruce Ritchey, the only actor among the cast of children) becomes the film’s token representative case study — someone Garland immediately “adopts” as her special-interest child (perhaps because he looks “normal”, in comparison to the other children, though her rationale is never made quite clear).

We’re shown flashbacks of the trauma his well-heeled, educated parents (Gena Rowlands and Steven Hill) experienced before finally realizing that their child was “defective”:

As Lancaster explains heatedly, and in all sincerity, to Garland, “His parents didn’t face the fact that he was retarded until very, very late; they let him play with ordinary children, and go to Kindergarten!” This kind of statement would be campily laughable if it weren’t so painfully representative of erstwhile attitudes.

The film’s best moments are those in which Cassavetes is allowed to show his directorial hand, and presents us with more authentic slices-of-life — most noticeably during the interactions between Rowlands and Hill (both wonderful):

and one short scene in which Paul Stewart shares his own experiences as the father of a child with intellectual challenges. In contrast, all scenes with either Lancaster or Garland simply smack of Hollywoodized “best intentions”:

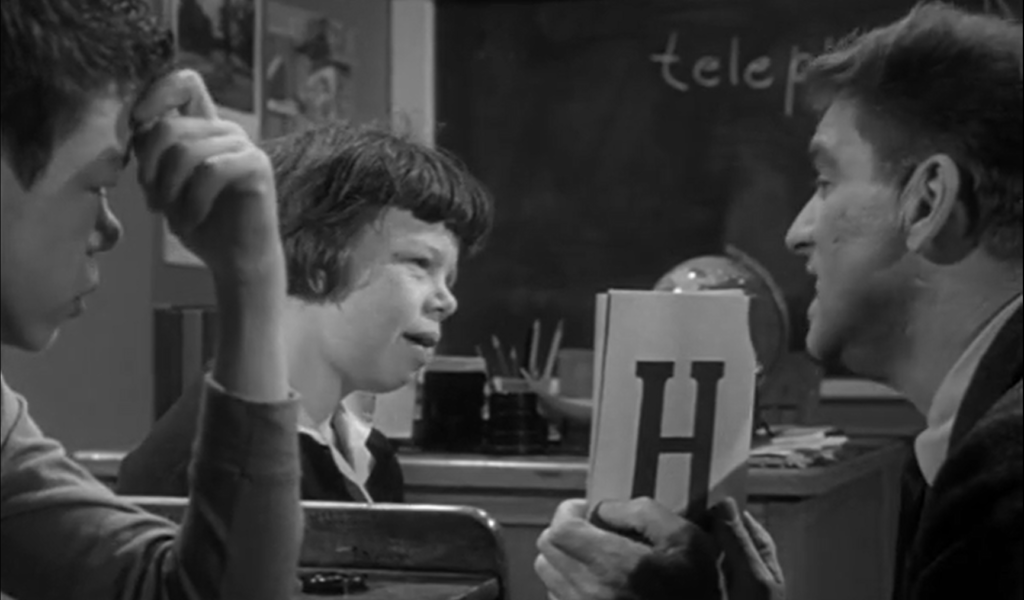

While many viewers (see IMDb) seem to adore both actors here, and to admire the film in general for its “daring” subject-matter, I’m not impressed by any of it (as should be clear by now!). Lancaster’s Dr. Clark represents a Firm-But-Kind Authority Figure who occasionally (for no apparent reason other than to allow us a refreshing glimpse of the “real” children) wanders through the school quizzing the students on their letter recognition skills (wouldn’t this be done by a trained speech pathologist?):

Meanwhile, Garland’s character isn’t nearly fleshed-out enough — she seems to simply be wandering the set in a state of dazed bewilderment (surely a reflection of her personal health at the time), and we quickly become desperate to see more spunk and vitality of some kind.

True Garland fans (and there are plenty of them!) probably won’t mind — but all other film fanatics should simply stick with watching her earlier films.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Bruce Ritchey as Reuben

- Gena Rowlands as Reuben’s mother

- Steven Hill as Reuben’s father

- Paul Stewart in a small but memorable role as a sympathetic school staff member

- Fine, if frustratingly intermittent, use of cinéma vérité techniques

Must See?

No, though most film fanatics will be curious to check it out once.

Links:

|

One thought on “Child is Waiting, A (1963)”

A once-must, for its subject matter.

While I’ll concede the validity of the points brought out in the assessment – and while I’m not an expert on the film’s topic, its rarity as the basis for a film (esp. at the time) makes it (I think) worthy of a look. Those with a deeper interest can always do further study elsewhere.

I’d seen this many years ago but I went into this rewatch with the idea of taking the film on its own terms. I believe those terms have more to do with the adult characters rather than the children. As Lancaster says at one point, in mild frustration to his secretary, “Y’know, sometimes I think we should be treating the adults instead of the children.” Hence, I feel the film is focused more on how adults react to / face children with developmental disabilities.

It’s probably important to consider that the script was inspired by the Vineland Training School in New Jersey. Although the school was involved in agriculture and pioneered work with challenged children from the mid-1800s, it didn’t establish its Division of Emotional Disturbance until 1970.

I mention that for two reasons: 1) The film suggests that more effective methods of treatment were either not-yet-known or not established as effective, and were to come later; Lancaster’s methods are referred to as “controversial”. 2) In line with that, the film reminds me of my own family – specifically my eldest brother, who was sent away for a period of time to a mental institution for shock therapy (one of the types no longer legal). Apparently, in the ’60s, they didn’t yet know how to establish that someone was clinically crazy – so they chose harsher, unproven methods for those who were just depressed and / or socially maladjusted.

Abby Mann was a solid screenwriter, so I’m assuming he took both his topic and his research seriously. I’ll agree that, in significant ways, the film is now very much a product of its time. But I tend to believe its sincerity – and its courage for tackling a very non-commercial subject.