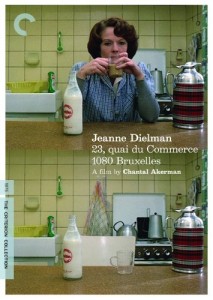

Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1976)

“See you next week, then.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Review: In Jeanne Dielman, however, director Chantal Akerman strips prostitution completely bare: there are no fancy outfits or make-up here; no cat calls; no dangerous street positioning; no pimps; no underlying psychological reasons for having entered into this profession. What we’re left with instead is a middle-aged homemaker and mother who happens to have sex for money with men on a regular basis. It’s never stated explicitly in the film, but it’s implied that neither Jeanne’s son nor any of her neighbors have any idea what she does to bring in money. Indeed, until the final moments of the film, not even the audience sees Jeanne servicing her Johns — all we are allowed to witness are scenes of Jeanne inviting a man into her bedroom; exiting a few seconds later (in a convenient time lapse); coldly accepting cash from him; and stating almost robotically, “See you next week, then,” before seeing the man out the door. Akerman’s three-hour long character study is ultimately concerned with chronicling the predictable minutiae of Jeanne’s daily life, as she takes care of her home, cooks for her son, answers letters from her sister, watches her neighbor’s baby, and runs various errands around town. None of this is inherently compelling, yet it’s strangely hypnotic to watch Jeanne pursuing her mundane rituals, day after day. Indeed, because so much time is spent showing the way Jeanne carefully maintains control over her life — and the frustration she feels when things don’t go just right — the shocking final moments of the movie seem almost like an inevitable outgrowth of her routine. It’s difficult not to impose one’s own interpretation onto a film like Jeanne Dielman, which leaves so much room for deliberation and conjecture. The unusual power of this marathon exercise in minimalism is the way in which we both accept Jeanne’s “final” action as natural, and find ourselves questioning everything that has come before. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |

One thought on “Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1976)”

POSSIBLE SPOILER WITHIN:

First viewing. Ultimately a must – its place as (stated) “a landmark in experimental European cinema” cannot be ignored – even film fanatics with a penchant for long, difficult films (and I sat through “Satantango” and “Berlin Alexanderplatz”, to name a few) may be tested here. There is very little dialogue (though what there is takes on weight) and the camera often remains stationary through long stretches as the protagonist completely washes dishes, has often-silent meals with her son, simply sits at a table staring ahead, etc. See what I mean? Still wanna see it?

As directed by Akerman, Delphine Seyrig eschews what is intriguing (and stunning) about her elsewhere in favor of a plain performance, in look and delivery…until midway, when the film begins building a vague momentum. Seyrig’s character is so fixated on getting things done, or else relaxing, that there seems little evidence of any kind of internal processing. Halfway, oddly, when Seyrig’s Jeanne is peeling potatoes (!) and undergoes a sudden, subtle shift (she begins dropping things, etc.), if the viewer doesn’t think he/she is watching paint dry, or is a fool for watching at all, it’s possible that a certain personal transference may develop (if it hasn’t started to already). Still wanna see it?

Watching Seyrig as Jeanne is rather like removing the other two stories in “The Hours” and simply following Julianne Moore’s taciturn character around. Although Jeanne is not as obviously depressed as the (esp. younger) woman Moore played, there is an overriding feeling that something is not sitting right with her. (Does this disturbance begin when Jeanne realizes her son is at an age where he will regularly talk of matters of sex? There is something disturbing in her tone when she evades his inquisitiveness with remarks like “Making love, as you say, is merely a detail.” and “It’s no use talking about these things.”) By the end, the viewer may be eerily reminded of news reporters speaking with neighbors of murderers who say things like, “I don’t understand. He was so quiet and seemed so friendly.” A cumulative effect sends its message home.

Though this film is (as stated) “demanding”, it is no doubt more so if seen in a theater. Very much recommended for a single viewing (who would sit through it twice?!). If it comes off as mundane while you’re watching it, don’t be surprised if it haunts you after.