“My name is Charly Gordon, and I live in a room, and I got no sister and no dog, and I am stupid!”

|

Synopsis:

Charly (Cliff Robertson), a mentally retarded bakery worker, undergoes an experiment in “intelligence enhancement”, and quickly becomes a genius — but the results are temporary–

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Character Arc

- Claire Bloom Films

- Cliff Robertson Films

- Mentally Retarded

- Romance

- Science Fiction

- Scientists

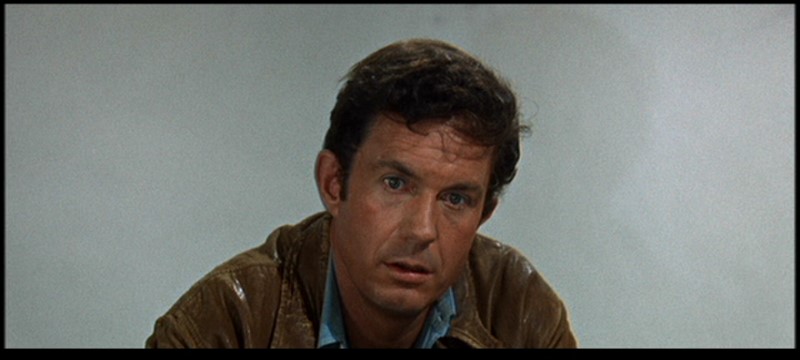

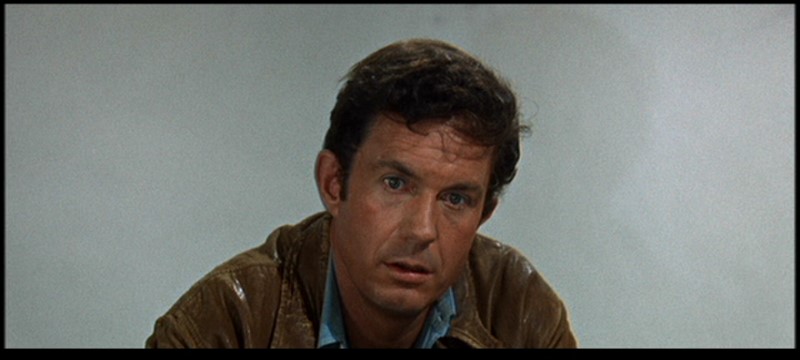

Response to Peary’s Review:

This “sometimes touching, sometimes soppy” sleeper doesn’t quite live up to the power of its source material — Daniel Keyes’ Hugo Award winning novella, Flowers for Algernon — yet remains a fascinating and provocative cautionary tale on the ethics of scientific experimentation. As Peary notes, Robertson does an excellent job in a difficult role, showing “that Charly is more lovable when retarded than when he is a genius,” yet making us realize the tragedy of Charly’s eventual regression. Claire Bloom as Charly’s case worker is lovely as always, and their brief romance is both touching and sad. You’re guaranteed to feel a lump in your throat by the end of this inevitably disastrous and heartbreaking story.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Cliff Robertson’s sensitive, multi-faceted portrayal as Charly

- Claire Bloom as Charly’s case worker and love interest

Must See?

Yes. While opinions vary on the ultimate success of this screen adaptation (see links below), it remains must-see viewing due to Robertson’s heartfelt, Oscar-winning performance.

Categories

- Noteworthy Performance(s)

- Oscar Winner or Nominee

Links:

|

2 thoughts on “Charly (1968)”

The fact that this remains interesting as a “cautionary tale on the ethics of scientific experimentation” is the only reason I consider it (not overly enthusiastically) a once-must. The subject matter saves ‘Charly’, even if I find the execution rather flawed.

Halfway-through, as he is reaching super-intelligence, Robertson is given a potent line: “I was wondering why people that would never dream of laughing at a blind or a crippled man will laugh at a moron.” Later on, this issue will become a matter of ‘Who are the real morons?’ as the more-advanced Robertson refers to the activities of the coming generation as “a beautifully purposeless process of society suicide.” This is the element which makes the film intriguing. The sequence in which Charly is called on to be on exhibit is the best one in the film.

However, I don’t find ‘Charly’ convincing enough to be very moved by it. While accepting (sometimes with leaps) the implausible aspect of what we’re watching, we’re also puzzled about Robertson’s particular kind of retardation; we’re subjected to usage of split-screen, boxed images, and other unnecessary or pretentious visual tricks; we’re thrown off the narrative path midway when the film devolves into a sappy love story – which blossoms from what seems to be near-rape! (…Happens, I suppose.)

His Oscar notwithstanding, I don’t think this is Robertson’s finest hour; nor was his part nearly as challenging as the one Alan Arkin was nominated for in the same year: ‘Singer’ in ‘The Heart is a Lonely Hunter’. Talk about a lump in the throat!

Worth viewing for its interesting subject matter and the acting of the two main stars. Looking at the various reviews on imdb everybody seems to have a different view on this film often contradicting each other: Cliff Robertson’s acting is either too maudlin or exactly spot on and that goes for nearly every other aspect.

One exception is that most people don’t like the split screens and other typical late Sixties effects. I actually love them, it’s part of the period and as long as it doesn’t become too flashy they create a certain mood. Furthermore the music by Ravi Shankar compliments many of the scenes and is definitely a bonus.

Agree that the attempted rape is uncomfortable viewing and the sudden change of heart by the Claire Bloom character rather unconvincing.

Should be viewed at least once.