|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Christopher Reeve Films

- Feminism and Women’s Issues

- Jessica Tandy Films

- Literature Adaptation

- Merchant Ivory Films

- Love Triangle

- Vanessa Redgrave Films

Review:

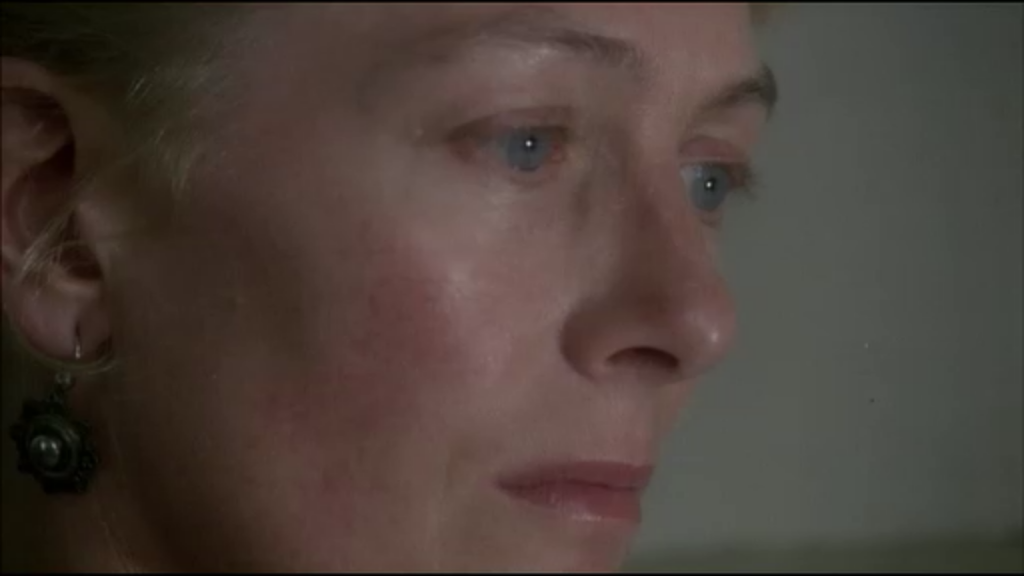

Merchant-Ivory’s adaptation* of Henry James’ tragicomic novel (which prompted the coining of the phrase “Boston marriage”) is apparently quite faithful to its source material (which I’ve never read) — up until its infamously modified final scene. Vanessa Redgrave deservedly won an Oscar nomination for her portrayal of a very thinly-veiled lesbian suffragette in post-Civil War Boston who falls head-over-heels in love with Potter from the moment she first hears her speak; meanwhile, Christopher Reeve gives one of his best non-Superman performances as the unapologetically prick-ish southern lawyer vying for Potter’s attentions. As the center of the battle between Redgrave and Reeve, Potter — an unconventionally cherubic beauty — is a controversial casting choice, but ultimately (I believe) suits the role: she exudes enough gentle charisma to convince one of her viability as a magnet for both suitors. This most unusual “love triangle” plays out against Merchant-Ivory’s typically lush period sets, and — despite a frustratingly melodramatic ending, and insufficiently explored characterizations — offers some subtly provocative statements about the nature of repression, longing, obsession, and rivalry.

* Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, long-time Merchant-Ivory collaborator, wrote the screenplay.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Vanessa Redgrave as Olive Chancellor (oddly excluded from Peary’s list of nominees in Alternate Oscars)

- Christopher Reeve as Basil Ransome

- Madeleine Potter as Verena Tarrant

- Fine supporting performances (in small roles) by Jessica Tandy, Linda Hunt, and Nancy Marchand

- Lovely sets and production values

Must See?

No, though it’s strongly recommended just to see Redgrave’s performance.

Links:

|

One thought on “Bostonians, The (1984)”

Not must-see, but instructive as a document of an important time in history.

This is the film James Ivory directed just before he and producer Merchant hit their 8-year stride of their best work as collaborators (6 films: ‘A Room with a View’ through to ‘The Remains of the Day’). As such, it’s an occasionally intriguing, though somewhat frustrating film bridging the director’s more experimental tendencies with his finely-woven signature work.

Its second half is more compelling than the first. Early on, with little set-up, we are thrown into a barrage of short scenes presumably intended to establish groundwork for what’s to come. It’s all a bit cumbersome overall but, once that hurdle has been achieved, the film settles down into a solid number of more rewarding scenes.

Although ‘The Bostonians’ is quite effective as a window into the suffragette movement from various male and female angles, the movement is not used as an engine to drive the film. Potter’s Verena is seen as charismatic-enough in an early speech to an attentive audience – but, throughout the film, she is not really placed before a crowd of listeners at all…making us eventually wonder how she manages to acquire such a strong following of public supporters in town halls. The bulk of the film becomes somewhat reminiscent of Mark Rydell’s film of ‘The Fox’ – with Redgrave in the petulant Sandy Dennis role (more or less). As the film progresses, you may find yourself wanting to know much more about the women’s movement – and less about Potter’s indecisive, flip-flop nature.

Redgrave is quite impressive (as she tends to be) as Olive; for her character’s sake, the ending works well. Those supporting her are generally fine – with Marchand standing out as a mother intent on securing her son’s future, even as she attempts to plow her way through Redgrave’s real motivation. (One might wish Hunt had more to do – she lends gentle insight, and I particularly like her observation about women in the movement being happier when a man joins their cause, as opposed to a woman.)

More than anything, the film succeeds in tackling the very thorny issue of suppressed homosexuality. Redgrave’s Olive may be a sad figure in her own denial, but she also possesses a strength which eventually helps her channel her onto more solid, hopeful ground.