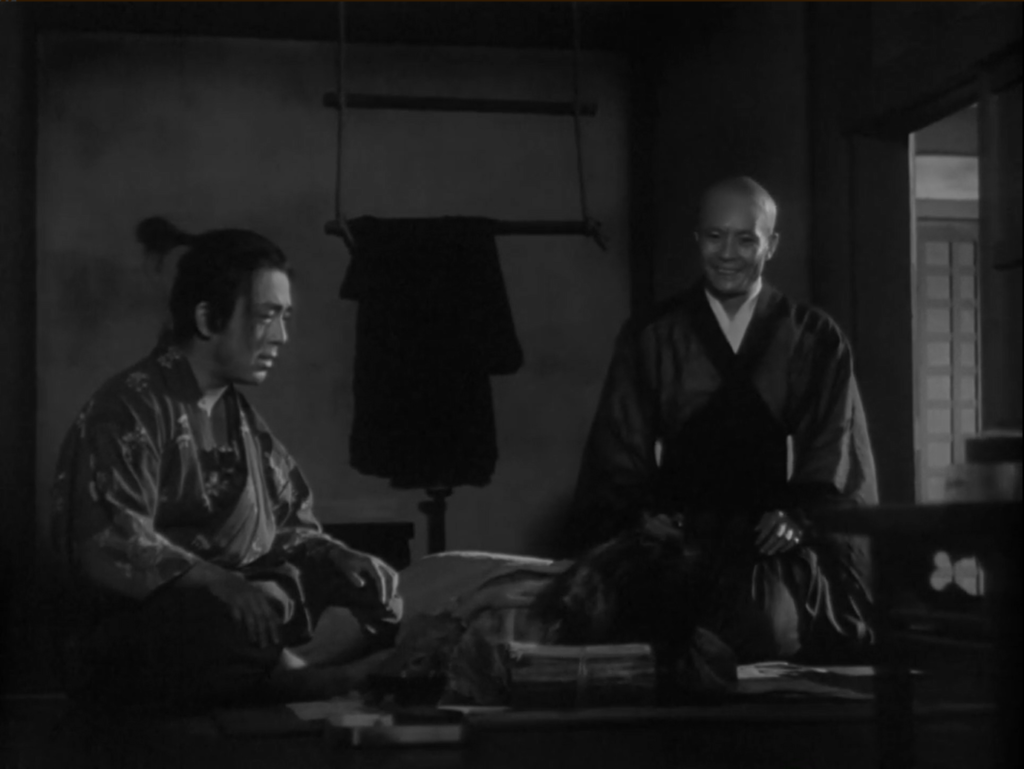

“Without compassion, a man is no longer human.”

|

Synopsis:

When a kind governor in medieval Japan is sent into exile because of his compassion for the local peasants, his wife (Kinuyo Tanaka), son (Masahiko Kato), and daughter (Keiko Enami) set out to find him, but are kidnapped and sold into slavery and prostitution. Years later, his adult son (Yoshiaki Hanayagi) is determined to reunite his family.

|

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Escape

- Japanese Films

- Kenzi Mizoguchi Films

- Slavery

Response to Peary’s Review:

This “exquisitely photographed”, “sweeping epic” by Kenji Mizoguchi is a true masterpiece of mid-century Japanese cinema. As Peary notes, the film “brilliantly evokes brutal inhumanity” during the 11th century, “yet also is a beautiful character piece centering on mother and children.” Unfortunately, as with Rene Clement’s Forbidden Games (1952), Sansho may ultimately be too devastating to withstand repeated viewings — but it should definitely be seen once by all film fanatics.

Redeeming Qualities:

- Lovely cinematography

- The final, haunting reunion scene between mother and son

Must See?

Yes. This film is a classic of world cinema.

Categories

- Foreign Gem

- Important Director

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|

One thought on “Sansho, the Bailiff (1954)”

Agreed, a must – probably in Mizoguchi’s top 5 best.

We’re told at the offset that ‘STB’ is based on a legend beloved by the Japanese; it’s easy to see why it’s remained a popular tale – and the film explores its admirable subjects: removal of tyranny, the rights of man, the importance of leading a moral life, endurance, family loyalty and kindness to others.

Since tyranny takes the upper hand here – and human life without obvious power is of little value, this is among the saddest films ever made. It’s even appropriately photographed in a sad way: shadows, mist, daylight skies that often seem to hide the sun. A large number of the locations are desolate.

Like Mizoguchi’s ‘Life of Oharu’, this film relates a series of hardships. Unlike ‘Oharu’, the hardships are of a piece, contained within a single situation and more believable. You’ll note, by the way, the intensity of the film’s first shocking sequence, in which Tanaka’s children are ripped from her (think Meryl Streep in ‘Sophie’s Choice’). A few other shocks occur, but Mizoguchi handles them subtly.

The performances are ensemble caliber: no one stands out and no one needs to; this creates a certain uniformity that allows us to concentrate on the severity of the situation as it plays out.

The film’s last scene certainly earns its power.