|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Boris Karloff Films

- Charles Laughton Films

- Horror Films

- James Whale Films

- Melvyn Douglas Films

- Old Dark House

- Psychopaths

- Raymond Massey Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

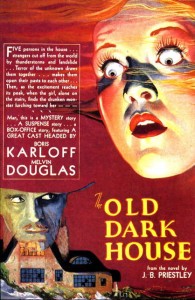

As Peary notes, this “splendid, much overlooked” (is it, still?) horror film by director James Whale “exhibits his usual flair, wit, sophistication, and fascination with perverse characters.” Indeed, as Peary points out, the “five inhabitants” of the titular house “make the eccentric families found in screwball comedies seem normal”: after being “greeted” at the front door by the family’s “mad, mute butler (Boris Karloff) with scars on his forehead, a scruffy beard on his chin, and a constant urge to drink himself into a violent rage”, the clueless visitors quickly encounter “elderly, prissy, cowardly, atheist Ernest Thesiger and his partially deaf, unfriendly, fanatically religious sister, Eva Moore” — only to find that the family’s eccentricity extends much further, as they are introduced to the elderly siblings’ “heavily-whiskered 102-year-old father” (played by a woman, Elspeth Dudgeon!), and the most mysterious family member of all (Brember Wills).

As Peary argues, the “film is outrageous from the outset and becomes increasingly bizarre”. Although “Whale displays tongue-in-cheek humor at the beginning to lull viewers into a false sense of security”, he then “plays up the suspense and terror in the final few scenes”. (If you’ve never seen Old Dark House, don’t read reviews, as most will give away spoilers, and it’s much more fun to simply watch how things unfold.) Peary points out that “as always, Whale makes dramatic use of shadows, sound effects, wild angles (especially when filming faces), and dramatic close-ups”, and notes that DP Arthur Edeson provides “standout [cinemato]graphy” which “greatly contributes to the atmosphere” (check out the stills below). Also of note is the stunning make-up work done for both Karloff and (in particular) Dudgeon.

Interestingly, Peary’s review neglects to point out the film’s historical significance as the forerunner of all such “old dark house” films. What’s especially remarkable is how successful Whale is at satirizing the nascent genre he was simultaneously introducing: as creepy as events do eventually become, we’re treated to plenty of campy humor throughout, notably in the laughably mundane romance which immediately flourishes between Douglas and Bond (their dialogue together is priceless), and in some of the banter offered by Thesiger and Moore (who are as kooky as all get out, but never posited as any kind of a genuine threat themselves). Meanwhile, the family members are such a collectively outlandish bunch — and the visitors’ reactions to them so hilariously muted — that, at least until the very end, one can’t help viewing the entire affair as some kind of fantastical joke.

Note: Modern film fanatics will naturally be interested to know that the gorgeous blonde here (Gloria Stuart) is none other than “Old Rose” from Titanic (1997).

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Fabulously creepy make-up

- Arthur Edeson’s cinematography

Must See?

Yes, as an early horror masterpiece by a famed director.

Categories

- Genuine Classic

- Important Director

Links:

|